The author is the director of dairy policy analysis at the University of Wisconsin.

Early in my career we never gave dairy trade a second thought. We exported a very small amount of dairy products - quite often surplus nonfat dry milk or butter. On the flip side, we imported a small amount of high-value cheese products not manufactured in this country. Basically, by milk equivalent volume, imports and exports offset one another and represented about 2 to 4 percent of milk production in any given year.

The U.S. did not export many dairy products because our domestic prices on items like cheese were two to three times higher than the so-called "world price" for similar products. Much of the reason for the price difference was because the European Union (EU) kept farm milk prices artificially high by taking excess products off of their domestic markets with export subsidies. This influenced world markets and caused dairy product prices to be artificially low.

The Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) concluded in 1994. In 1995, 128 countries, including the European Communities, became founding members of the new World Trade Organization (WTO). Europe agreed to a schedule of reduced agricultural subsidies and ultimately to give them up altogether. This action lowered Europe's farm milk prices and allowed world milk prices to rise.

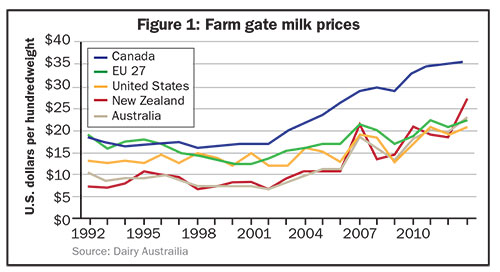

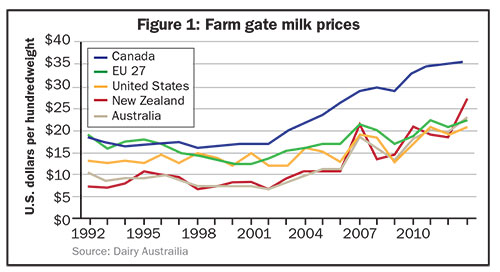

You can see the path of farm gate milk price changes over time in Figure 1. Initially, the EU and Canadian milk prices were about equal . . . and nearly double those of Australia and New Zealand. The U.S. prices were just about in the middle. By 1997, the EU milk prices were dropping to U.S. levels and the world dairy prices started to rise. This was a hard transition for EU dairy farmers . . . Australia and New Zealand producers were the clear winners in this policy change.

From 2003 to 2007, the U.S. dairy industry was in transition. We began to discover export opportunities when rising world dairy product prices allowed U.S. manufacturers to be price competitive. But we found that overseas customers were different than domestic customers.

They expected products in kilogram and liter packages - not pounds and gallons. They wanted 82 percent butterfat for their butter and not our 80 percent product. Most countries want protein standardized skim milk powder and not nonfat dry milk powder. Furthermore, it is almost unheard of to color cheese in other countries and Gouda is the currency for trade, not Cheddar.

The U.S. Dairy Export Council (USDEC) was founded in 1995 just after the Uruguay Round of GATT. USDEC's founding mission was to represent the global trade interests of U.S. dairy producers, proprietary processors and cooperatives, ingredient suppliers and export traders. Eight years later, Cooperatives Working Together, or CWT, was launched with a portion of their mission to help subsidize occasional exports of product. It was recognized that the transition to becoming a consistent supplier to world markets might need help during times when our domestic prices were somewhat higher than world markets. By 2007, this help was needed far less often as the farm gate milk prices of the world's major dairy export countries all converged.

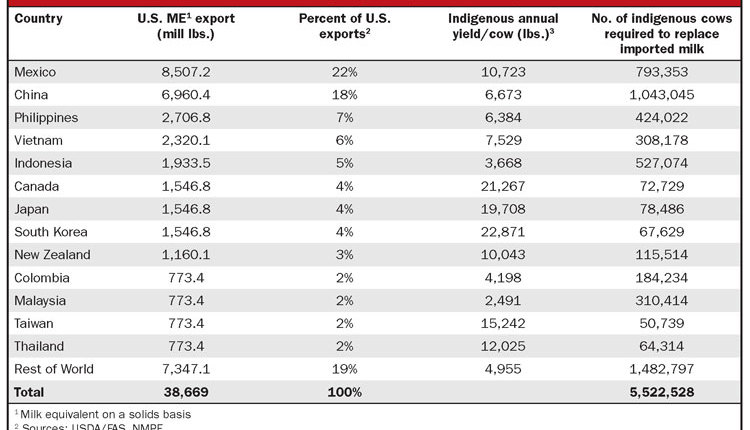

New Zealand and the EU are the world's largest exporters, with about one-third of the volume of world trade each. However, the U.S. stands alone in third place with a little more than 20 percent and Australia is a distant fourth place with about 7 percent of world trade.

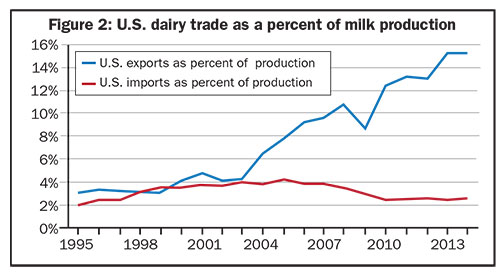

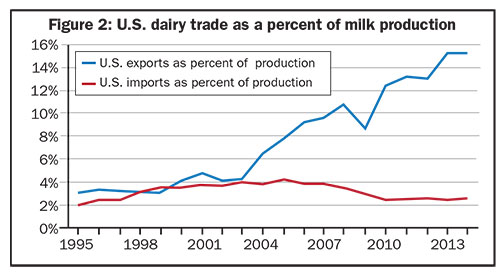

The U.S. volume of exports now represents somewhat more than 15 percent of our total milk production and has been growing at an annual rate of more than 13 percent per year since 2003. That growth is detailed in Figure 2.

The trade story for the U.S. has been even better than that. Over that same time period, imports of dairy products have declined. Part of the reason was a weakening of the U.S. dollar relative to other currencies (this makes imported products look more expensive to us and exported products look less expensive to our overseas customers), and the U.S. began to produce more varieties of cheeses that we once imported. Together, the improved net exports have accounted for about two-thirds of our growing milk production since 2003. The remaining one-third of milk production gains were sold to our expanding domestic population.

Exports have been good for the U.S. dairy industry. However, it is important that our milk prices are well aligned with those of other exporting countries. If our price becomes much higher, then we are not competitive. And, when export sales represent more than 15 percent of our milk production, we cannot absorb that much product back into our domestic market.

Click here to return to the Dairy Policy E-Sources

150810_487

Early in my career we never gave dairy trade a second thought. We exported a very small amount of dairy products - quite often surplus nonfat dry milk or butter. On the flip side, we imported a small amount of high-value cheese products not manufactured in this country. Basically, by milk equivalent volume, imports and exports offset one another and represented about 2 to 4 percent of milk production in any given year.

The U.S. did not export many dairy products because our domestic prices on items like cheese were two to three times higher than the so-called "world price" for similar products. Much of the reason for the price difference was because the European Union (EU) kept farm milk prices artificially high by taking excess products off of their domestic markets with export subsidies. This influenced world markets and caused dairy product prices to be artificially low.

The Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) concluded in 1994. In 1995, 128 countries, including the European Communities, became founding members of the new World Trade Organization (WTO). Europe agreed to a schedule of reduced agricultural subsidies and ultimately to give them up altogether. This action lowered Europe's farm milk prices and allowed world milk prices to rise.

Prices changed sales

You can see the path of farm gate milk price changes over time in Figure 1. Initially, the EU and Canadian milk prices were about equal . . . and nearly double those of Australia and New Zealand. The U.S. prices were just about in the middle. By 1997, the EU milk prices were dropping to U.S. levels and the world dairy prices started to rise. This was a hard transition for EU dairy farmers . . . Australia and New Zealand producers were the clear winners in this policy change.

From 2003 to 2007, the U.S. dairy industry was in transition. We began to discover export opportunities when rising world dairy product prices allowed U.S. manufacturers to be price competitive. But we found that overseas customers were different than domestic customers.

They expected products in kilogram and liter packages - not pounds and gallons. They wanted 82 percent butterfat for their butter and not our 80 percent product. Most countries want protein standardized skim milk powder and not nonfat dry milk powder. Furthermore, it is almost unheard of to color cheese in other countries and Gouda is the currency for trade, not Cheddar.

The U.S. Dairy Export Council (USDEC) was founded in 1995 just after the Uruguay Round of GATT. USDEC's founding mission was to represent the global trade interests of U.S. dairy producers, proprietary processors and cooperatives, ingredient suppliers and export traders. Eight years later, Cooperatives Working Together, or CWT, was launched with a portion of their mission to help subsidize occasional exports of product. It was recognized that the transition to becoming a consistent supplier to world markets might need help during times when our domestic prices were somewhat higher than world markets. By 2007, this help was needed far less often as the farm gate milk prices of the world's major dairy export countries all converged.

Our place in the world

New Zealand and the EU are the world's largest exporters, with about one-third of the volume of world trade each. However, the U.S. stands alone in third place with a little more than 20 percent and Australia is a distant fourth place with about 7 percent of world trade.

The U.S. volume of exports now represents somewhat more than 15 percent of our total milk production and has been growing at an annual rate of more than 13 percent per year since 2003. That growth is detailed in Figure 2.

The trade story for the U.S. has been even better than that. Over that same time period, imports of dairy products have declined. Part of the reason was a weakening of the U.S. dollar relative to other currencies (this makes imported products look more expensive to us and exported products look less expensive to our overseas customers), and the U.S. began to produce more varieties of cheeses that we once imported. Together, the improved net exports have accounted for about two-thirds of our growing milk production since 2003. The remaining one-third of milk production gains were sold to our expanding domestic population.

Exports have been good for the U.S. dairy industry. However, it is important that our milk prices are well aligned with those of other exporting countries. If our price becomes much higher, then we are not competitive. And, when export sales represent more than 15 percent of our milk production, we cannot absorb that much product back into our domestic market.

150810_487