The author owns The McCully Group LLC, which provides management consulting for dairy and food companies.

In May, the U.S. dairy herd expanded to its highest level in 27 years, climbing to over 9.5 million head. This contrasts to a rather tight window from 2000 to 2016 when dairy cow numbers ranged between 9 to 9.3 million head. That 300,000-cow movement, both up and down, coincided in response to changes in dairy farm margins. After 2017, cow numbers moved to near 9.45 million head before dropping back in 2018 and 2019 due to poor farm margins. However, since July 2019, dairy cow numbers rose 187,000 head to the current multi-decade high.

While there are many reasons for this quick ascent in cow numbers, people point to the use of gender-selected semen along with growth in large dairy farms ranking among the main reasons for the abnormally high cow numbers. However, there’s a new factor that is expected to significantly alter how dairy farms respond to market signals.

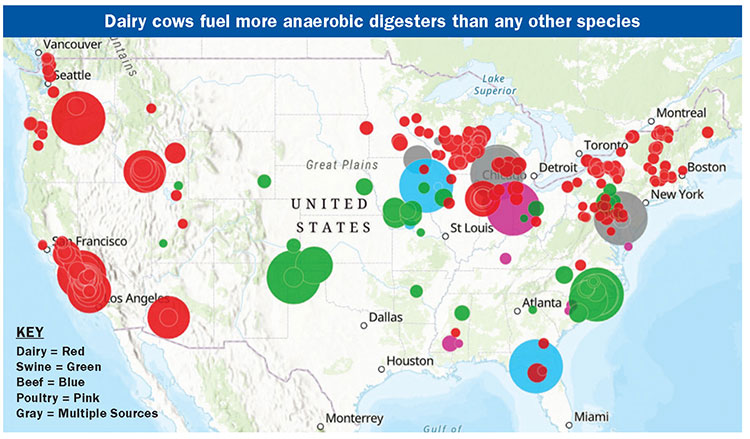

Methane digesters are being built on dairy farms, particularly on large farms in the western half of the U.S. These digesters generate a new revenue stream for the farms. California has seen significant growth in this area in response to the state’s renewable fuels market more formally known as the low-carbon fuel standard (LCFS).

A big carbon intensity score

The LCFS is a fuel-neutral, market-based state program designed to reduce the life cycle carbon intensity (CI) of transportation fuels by encouraging the use of cleaner, low-carbon fuels. Given the large negative CI score from livestock manure, the renewable natural gas (RNG) produced from it offers the highest LCFS credits.

Dairy farms are ideal sources of raw material given the volume of manure produced per cow along with the ability to collect it in confinement operations. This has attracted energy companies, private equity firms, industrial conglomerates, and others looking to invest in digester projects. In some cases, payback on the investment can be less than three years.

While the program is California-based, RNG generated out-of-state is eligible for LCFS credits if the gas is injected into a natural gas pipeline with the ability to flow to California. This has led to significant growth in anaerobic digestion projects across the country that inject their RNG into pipelines for sale in California.

As of April 2021, there were 270 dairy farms and over 700,000 cows listed in the EPA Livestock Anaerobic Digester database. There are several large known projects that are not included, which brings the total closer to one million cows or roughly 10% of the U.S. dairy herd.

A new enterprise

The profit generated by manure and energy is a new dynamic for dairy farms. A common arrangement is for a third party to invest in the digester and form an agreement with one or more dairy farms for a supply of manure. These contracts can be for 10 to 15 years or longer and pay $80 to $100 per cow per year or more. For a 3,500-cow dairy, that means $350,000 per year or 40 cents per hundredweight based on an 80 pound per day tank average. Some farms own the digesters, taking on the risk, but reaping potentially larger rewards. If the profits are $2 to $3 per hundredweight, they could likely exceed the profit from milk. At that point, milk has become the by-product of manure production.

Consider the future

A large unknown is the regulatory risk from future policies and credits for RNG and other renewable energy sources. Some predict the California market could become saturated in several years, leading to a rush to get projects in place now. However, other states are developing similar programs to California, and green infrastructure money from the federal government is expected to lead to further growth in methane digester projects.

There are major implications to the dairy industry as dairy farms become a source of green energy. First, scale is important when building a digester to generate renewable natural gas, so they are built either on or near very large dairy farms. Location near existing gas pipelines is also essential. Some projects include a centralized digester facility that can take in manure from 20,000 to 25,000 cows, while on-farm digesters can be built for smaller dairies. Projects are also producing “raw biogas” and then trucking it to a centralized gas cleaning facility near a pipeline.

Unintended consequences

In addition to lower cost of production, the returns from energy generated by large farms may accelerate the growth of the mega-dairy farms. At the onset, small farms may find it more difficult to participate in these projects. However, there are examples of smaller scale digester projects that also use food waste and other feedstocks to produce RNG or electricity. The trend is for fewer, larger dairy farms, and government energy policy, while well-meaning, could have the unintended consequence of driving additional consolidation in the dairy farm sector.

How much of a factor is RNG and dairy farms in today’s dairy markets? It’s hard to know, but if 10% of the cows are on farms with methane digesters, it is likely having an impact. Going forward, cows fueling digesters will only grow.

In the past, a drop in dairy farm margins would lead to greater culling, farm sellouts, and eventually, lower cow numbers and milk production. However, as farms have contractual agreements to supply manure to digesters, they will be limited in how many cows they can cull and still meet their commitments. In addition, if they reduce cow numbers, they’ve reduced the revenue generated from their digesters.

The net effect will be that dairy farms with methane digesters and other green energy technologies will make decisions based more on returns from energy than returns from milk. It fundamentally changes dairy farm economics as well as milk and dairy product prices. If this comes to fruition, dairy market signals to raise or reduce milk production will be less effective. This could lead to a structural oversupply of milk in the domestic market, and thereby, heighten the importance of innovation in dairy products for both domestic and export markets.

The important questions

The focus on green energy generation and the benefits to dairy farms are positives for the industry. However, there are a number of questions the industry needs to answer.

- How can supply adjust to market signals?

- What are the unintended consequences of further dairy farm consolidation on the fabric of rural communities?

- Can jobs operating digesters create enough economic stimulus to offset the impact of small farms closing?

- How can the nutrients from manure continue to be captured and separated as fertilizer to better be utilized on farm fields or off the farm in the case of phosphorus?

- Can dairy product innovation be accelerated to find an outlet for additional supply?

The industry needs to understand the potential impacts now to create strategies that answer these questions and create an economically and environmentally robust tomorrow.