In the June 2013 issue of Hoard's Dairyman, on page 399, Brad Rach and I authored the article "Co-ops and dairy producers hold fewer cards" about the nation's largest dairy processors. Those processors are getting bigger, and not only are they more likely to be privately-owned, they are also more likely to be foreign-owned.

In this article, I want to discuss further why we should care that the processors are getting so big. I want all of us to better understand why what economists term "corporate concentration" is something we all need to be concerned about.

No matter where I look, I see evidence that agriculture is more dominated by corporations that are merging, buying competitors and otherwise doing everything they can to super-size their market share. Already, the top four corporations slaughter four out of five cows, process two out of three hogs and three out of five chickens, and sell half of all groceries.

Merger mania continues

In spite of these shocking numbers, merger mania continues. Here are just a few examples from the last couple of months:

- The largest meatpacker in China is trying to buy Smithfield, our nation's largest pork processor.

- Two of our largest flour millers, Cargill and ConAgra, are proposing a merger.

- ConAgra bought Ralcorp, another giant in the food processing business.

- Heinz was bought by Berkshire Hathaway.

What a difference a year makes. If you turn to page 690 of this issue, you will see the recently updated 2012 top processor list. The top processor is now foreign owned and there are no co-ops among the top four.

These numbers are for the nation as a whole. Regional numbers are often higher. For example, in 2009 the Department of Justice got involved when Dean Foods Company bought Foremost Farms USA's Consumer Products Division. The acquisition (later blocked) gave Dean 57 percent of the market for processed milk in northeastern Illinois, Michigan's Upper Peninsula and Wisconsin. Compare that to Dean's 12.5 percent national share of the top 50 processors.

Where are the milk buyers?

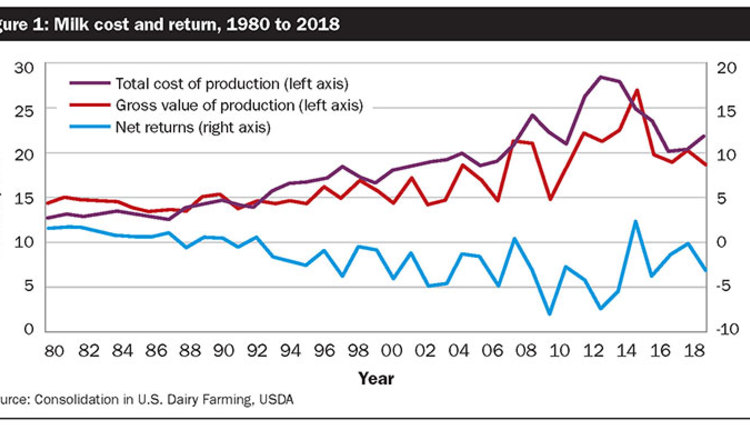

That's enough number crunching for a minute. Think back and ask yourself this: Do I have as many buyers looking for my milk as I did 20 years ago? My guess is that every dairy farmer in America will answer that question with an emphatic "NO." What that means is that buyers can more easily pit dairy farmers against each other in a never-ending search for lower milk prices.

Low farm prices are not the only reason to be concerned over corporate concentration in agriculture. It was my good fortune to participate in a Food and Water Watch project that led to a report called "The Economic Cost of Food Monopolies." We looked at different ways corporate concentration is standing in the way of prosperity for farmers and their communities.

One of the key findings was that corporate concentration drains value from rural communities and transfers it to distant investors. As part of the project, we asked agricultural economists at the University of Tennessee to assess the contribution of additional hog production in Iowa. Their conclusion was shocking even by my jaded standards: "Adding an additional 1,000 hogs in a county reduced total income in that county by $592." You read that right. Reduced.

The report also gave examples of how giant corporations reformulate products in ways that hurt farmers, encourage industrial-sized farms over family-sized farms, and use their global reach to play entire countries against each other. And, if that wasn't bad enough, the report only touched on the most powerful sector of all in the food system - retailing.

Retailers fuel price wars

In food retailing, the market share of the top four corporations is high and growing rapidly. In 2010, the four biggest food retailers sold 53 percent of groceries, a number well above the 40 percent threshold that sparks concern among economists. As retail concentration grew, the market share of independent supermarkets nearly vanished. In 2010, 19 out of 20 supermarkets in America were owned by chains operating at least 11 stores.

As with dairy processing, food retail concentration is often much higher in local and regional markets. For example, in some metro areas, the four biggest grocery chains sell more than 70 percent of the groceries. In 29 metro areas, Wal-Mart alone has more than a 50 percent market share.

For those of you who once thought the organic sector was immune to the effects of consolidation, it is time to think again. Super centers and traditional supermarkets have largely eclipsed food cooperatives and specialty stores as primary outlets for organic food. Most of the national organic brands have been snapped up by conventional food processors and grocery retailers are moving to private-label, store-brand organic processed foods.

What about free markets?

I want to say a few final words from the perspective of a guy who has spent his entire career with one foot on the farm and the other in the economics classroom. Hundreds of college students have struggled to stay awake while I droned on about the technical definition of free markets. Now, you get the short version: The agribusiness and retailing corporations that farmers must face are too big to meet those technical definitions. We can no longer count on free markets to save us.

Every dairy farmer who intends to stay in for the long haul needs to be thinking about how he or she will respond to corporate concentration. As I see it, there are three choices. The first is to find a place to hide. The second is to look to Washington. The third is to work with your neighbors to build market share.

I hope you make the right choice.

Read more articles on the Hoard's Dairyman feature page.