The author is director of dairy services at Informa Economics, Eagan, Minn.

U.S. milk prices are headed lower. At 11:59 p.m. on New Year's Eve, you can say with some certainty that the big ball will drop soon. Likewise, the dairy industry facts are rather clear: U.S. milk prices are at or near record highs, milk production is not only growing in the U.S. but across the other major exporters, feed costs are shifting dramatically lower, and U.S. dairy prices are currently trading well above the down-trending world markets.

Given these facts, it's hard to argue for anything other than lower milk prices during the second half of 2014 and into 2015. The uncertainty in the outlook is how far will prices fall and when will they start to recover? The good news is we think the underlying global demand is strong enough to keep farm level margins above breakeven at least into 2015.

A great run

The 12-month period from July 2013 to June 2014 was simply amazing. Milk production across the five major exporters (European Union, New Zealand, U.S., Australia and Argentina) expanded by the most we've ever seen in a 12-month period. Combined production was up 20.3 billion pounds for the 12 months, and yet we also experienced record-high milk and dairy product prices during this period. If production is up, and so are prices, the only conclusion you can draw is that demand must have also been strong.

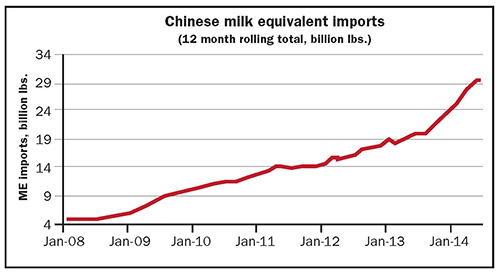

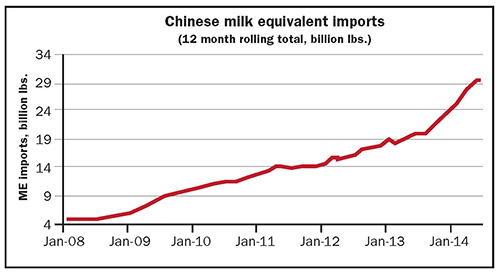

China has been an important driver of global demand growth since 2008, but over the last 12 months they were unequivocally the driver on the demand side which pushed prices to record highs. For the 12-month period June 2013 to May 2014, Chinese milk equivalent imports were up 9 billion pounds, while imports by the rest of the world were down 1.6 billion pounds. Chinese importers wanted a lot of milk, and they were willing to pay a high price to get it, effectively outbidding the rest of the world.

If Chinese imports are going to continue to grow at their recent pace, then there is no reason to believe that milk prices have to fall anytime soon. So, what has driven this surge in Chinese imports and can we expect it to continue?

The China effect

Anecdotal reports coming out of China in late 2013 suggested that their domestic milk production was falling below levels from a year ago due to high feed costs, fewer milk collection stations to collect milk from small farmers, poor weather, an outbreak of foot and mouth disease, and high beef prices. Informa Economic's modeling suggested that milk production was likely down in the range of 1 to 10 percent for calendar year 2013.

The Chinese Ministry of Agriculture, not always known for releasing statistics that jive with facts on the ground, estimated that production was down 5.7 percent, which actually looks reasonable. The 5.7 percent drop translates into a 4.7 billion pound drop in their cow milk production. Their imports for calendar 2013 were up 6.9 billion pounds, suggesting a very mild 1.8 percent growth in per capita consumption, which again looks reasonable.

Anecdotal reports in mid-2014 suggest that domestic production in China is improving and some of the surge in imports has ended up in inventory. The price of New Zealand sourced whole milk powder at Fonterra's Global Dairy Trade auction has dropped 39 percent from $2.25 per pound in early February to just $1.36 in mid-July. New Zealand sourced SMP has dropped from $2.29 per pound to $1.54 in the same time period.

Chinese importers have reportedly been slow to book supplies for the second half of 2014 and into 2015. U.S. prices will need to be competitive against the other major exporters and within the U.S. With NFDM prices still running at a $1.70-plus range, there is a significant short-term downside expected. However, we think the slowdown in Chinese orders is temporary as they work down inventory and wait for lower prices before placing orders again.

Signal says stop growing

Current prices in Oceania are down to breakeven for dairy farmers. The market is essentially telling dairy farmers in exporting countries to stop growing.

Does this signal make sense?

We don't think so.

The other importing countries, who were priced out of the market by China in late 2013 and early 2014, will take advantage of these lower prices and boost orders. Even with some mild growth in Chinese domestic milk production, it still looks like they will need to grow milk equivalent imports by 3 to 6 billion pounds per year to meet their growing consumer demand. If the world wants more milk in 2015, it will need to keep milk prices above breakeven.

U.S. prices have some significant downside possible as prices play catch-up with a currently weak world market. We expect prices on the world market to bounce a little higher in the fourth quarter, but U.S. prices may not bottom out until the first or second quarter of 2015.

The good news is that with feed costs shifting lower, we expect farm level margins for U.S. dairy farmers to remain positive through the first half of 2015.

This article appears on page 571 of the September 10, 2014 issue of Hoard's Dairyman.

U.S. milk prices are headed lower. At 11:59 p.m. on New Year's Eve, you can say with some certainty that the big ball will drop soon. Likewise, the dairy industry facts are rather clear: U.S. milk prices are at or near record highs, milk production is not only growing in the U.S. but across the other major exporters, feed costs are shifting dramatically lower, and U.S. dairy prices are currently trading well above the down-trending world markets.

Given these facts, it's hard to argue for anything other than lower milk prices during the second half of 2014 and into 2015. The uncertainty in the outlook is how far will prices fall and when will they start to recover? The good news is we think the underlying global demand is strong enough to keep farm level margins above breakeven at least into 2015.

A great run

The 12-month period from July 2013 to June 2014 was simply amazing. Milk production across the five major exporters (European Union, New Zealand, U.S., Australia and Argentina) expanded by the most we've ever seen in a 12-month period. Combined production was up 20.3 billion pounds for the 12 months, and yet we also experienced record-high milk and dairy product prices during this period. If production is up, and so are prices, the only conclusion you can draw is that demand must have also been strong.

China has been an important driver of global demand growth since 2008, but over the last 12 months they were unequivocally the driver on the demand side which pushed prices to record highs. For the 12-month period June 2013 to May 2014, Chinese milk equivalent imports were up 9 billion pounds, while imports by the rest of the world were down 1.6 billion pounds. Chinese importers wanted a lot of milk, and they were willing to pay a high price to get it, effectively outbidding the rest of the world.

If Chinese imports are going to continue to grow at their recent pace, then there is no reason to believe that milk prices have to fall anytime soon. So, what has driven this surge in Chinese imports and can we expect it to continue?

The China effect

Anecdotal reports coming out of China in late 2013 suggested that their domestic milk production was falling below levels from a year ago due to high feed costs, fewer milk collection stations to collect milk from small farmers, poor weather, an outbreak of foot and mouth disease, and high beef prices. Informa Economic's modeling suggested that milk production was likely down in the range of 1 to 10 percent for calendar year 2013.

The Chinese Ministry of Agriculture, not always known for releasing statistics that jive with facts on the ground, estimated that production was down 5.7 percent, which actually looks reasonable. The 5.7 percent drop translates into a 4.7 billion pound drop in their cow milk production. Their imports for calendar 2013 were up 6.9 billion pounds, suggesting a very mild 1.8 percent growth in per capita consumption, which again looks reasonable.

Anecdotal reports in mid-2014 suggest that domestic production in China is improving and some of the surge in imports has ended up in inventory. The price of New Zealand sourced whole milk powder at Fonterra's Global Dairy Trade auction has dropped 39 percent from $2.25 per pound in early February to just $1.36 in mid-July. New Zealand sourced SMP has dropped from $2.29 per pound to $1.54 in the same time period.

Chinese importers have reportedly been slow to book supplies for the second half of 2014 and into 2015. U.S. prices will need to be competitive against the other major exporters and within the U.S. With NFDM prices still running at a $1.70-plus range, there is a significant short-term downside expected. However, we think the slowdown in Chinese orders is temporary as they work down inventory and wait for lower prices before placing orders again.

Signal says stop growing

Current prices in Oceania are down to breakeven for dairy farmers. The market is essentially telling dairy farmers in exporting countries to stop growing.

Does this signal make sense?

We don't think so.

The other importing countries, who were priced out of the market by China in late 2013 and early 2014, will take advantage of these lower prices and boost orders. Even with some mild growth in Chinese domestic milk production, it still looks like they will need to grow milk equivalent imports by 3 to 6 billion pounds per year to meet their growing consumer demand. If the world wants more milk in 2015, it will need to keep milk prices above breakeven.

U.S. prices have some significant downside possible as prices play catch-up with a currently weak world market. We expect prices on the world market to bounce a little higher in the fourth quarter, but U.S. prices may not bottom out until the first or second quarter of 2015.

The good news is that with feed costs shifting lower, we expect farm level margins for U.S. dairy farmers to remain positive through the first half of 2015.