What is not clear is how these seemingly small decisions early in life impact cows two or even three years later. The goal of this article and the ones that will follow is to further the understanding of this phenomenon.

Aiming for more milk

The debate between limit-feeding milk replacer to encourage dry feed intake versus more aggressive feeding of milk or milk replacer has been a talking point within the calf community for years. Arguably, the greatest impact on how we feed calves resulted from a publication out of Cornell University in 2012. By now, the numbers from this study are considered common knowledge to some.

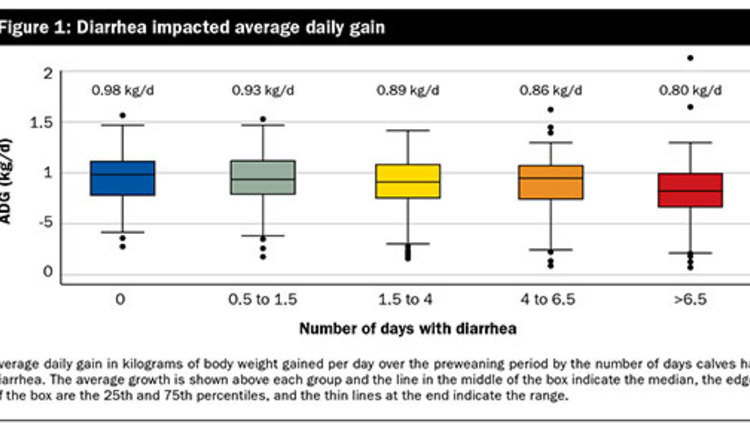

Two farms were utilized, and for every 2.2 pounds per day increase in body weight gain during the preweaning period, an improvement in first-lactation milk yield of 1,874 and 2,454 pounds was seen on Farm 1 and Farm 2, respectively. Realizing these results consistently may be folly, however, as raising body weight gain by 2.2 pounds per day is not easy.

Another common error in the interpretation of this data is that these future milk yield values were correlated with average daily gain, not milk intake. Although milk or milk replacer intake heavily influence gain in early life, other factors impact growth as well.

The situation becomes even more complex when one considers that feeding a higher plane of nutrition can also impact growth through indirect means, such as aiding in the fight against insults to the immune system. However, the question still remains: What happens to the calf as a result of better feeding in early life that may be responsible for growth in future milk yield?

How the mammary gland develops

Since the mammary gland is the milk-producing organ, it is logical to hypothesize that early nutrition may impact this organ and be at least partly responsible for improvements in future milk yield. The mammary gland is an unusual organ. While most organs are well established at birth, the mammary gland is not. The mammary gland experiences a majority of its growth after birth.

Just as we can program the fetus while in the uterus as development is occurring, it has been hypothesized by some that we can fetal program the mammary gland after birth, when it experiences its critical stages of development. Growth of the developing mammary gland is described in two distinct phases: 1) isometric and 2) allometric. Isometric growth is used to describe an organ that is growing at the same rate as the body. Allometric growth indicates that the organ of interest is growing at a rate faster than the body.

Allen Tucker and his lab at Michigan State University were among the first to use allometric growth to describe the growth of the mammary gland. That phase was reserved for the period between roughly 2.5 months of age and attainment of puberty, pregnancy, and early lactation. Until 2.5 months of age, the mammary gland was thought to be relatively dormant. Recent data has indicated that the mammary gland is actually incredibly active in early life, growing in size by greater than 60-fold in the first 90 days. This discovery has given understanding that early life mammary gland development may be critical to future productivity.

Two other terms deserve attention in regard to the mammary gland: mammary parenchyma and mammary fat pad. The mammary parenchyma is the functional tissue of the gland that will develop into the tissue that will produce and secrete milk.

The mammary fat pad surrounds the parenchyma. The fat pad serves as a support structure to the parenchyma by not only facilitating signaling to the parenchyma but also serving as physical support as the parenchyma grows and develops into the mammary fat pad. As the animal matures, the parenchyma spreads into the fat pad, taking up a greater proportion of the mammary gland to prepare for milk synthesis.

We know that feeding a higher plane of nutrition influences body growth and immune response. We also know that early life decisions influence future milk yield. In one study, feeding 4 versus 2 liters of colostrum to newborn Brown Swiss calves raised 305-day M.E. milk by 5,747 pounds through two lactations.

Elevating the plane of nutrition in another study by feeding unlimited whole milk twice daily (versus a conservative milk replacer diet) improved first-lactation milk yield by 2.7 pounds per day. Other research found that unlimited whole milk feeding resulted in a 10.3 percent improvement in first-lactation milk yield compared with unlimited milk replacer feeding.

Due to these findings, mention of the Lactocrine hypothesis has surfaced. The Lactocrine hypothesis states that factors in whole milk or colostrum (compared to milk replacer) may be at least partly responsible for the jump in milk yield. However, it must be remembered that the differences observed from the earlier mentioned Cornell study were actually found when milk replacer intake was stepped up.

In regard to the mammary gland, we know that the milk replacer diet offered can influence the size and lipid content of the fat pad in the growing calf. Recent work out of both Cornell and Michigan State have shown that diet may be able to influence growth of the mammary parenchyma in early life. It has been concluded, however, that the mammary parenchyma is not as nutrient responsive as the mammary fat pad.

More to the puzzle

When all of this data is analyzed, what is still missing is the explanation behind how nutrition can impact the growing mammary gland, and what these changes mean to the calf. If improved feeding to young calves truly leads to more future milk yield, what is responsible? What changes occur in the young calf as a result of feeding a higher plane of nutrition that can explain differences in first lactation?

Hopefully, the above discussion has led to a better understanding of what is happening in the mammary gland during the preweaning period. In future articles, we will help justify your decision to feed calves better with the goal of improving the lactation potential of your heifers.

Second issue: We can influence mammary growth

Third issue: Kick-start udder development