The icing on the cake is that the new forage being produced meets the needs of the high-producing cows at their lactation peak. Protein equal to good alfalfa, and energy almost equal to corn silage, wrapped in one crop, can support a lot of milk and components. Multiple farms are growing it as they found it reduces or eliminates “summer slump” when it gets hot out.

The crop we are talking about is winter forage. Winter grains, primarily winter triticale or winter rye, are grown with optimum management for production of high-quality forage. Initially, it was simply a cost-shared cover crop in most Northern areas. Double crop was something they did south of the Mason-Dixon Line. It has now moved across the country and north of the Canadian border.

Over the past 18 years, we have brought the crop from an afterthought for soil erosion to a critical pillar of profitable dairy production. As one farmer said, “Now I don’t know if I am a corn silage grower who also grows winter forage; or a winter forage grower who also grows corn silage.” The crop has moved into the forefront of their cropping program because of the many benefits, plus any addition to the crop toolbox reduces the risk of catastrophic crop failure.

Achieve yield and quality

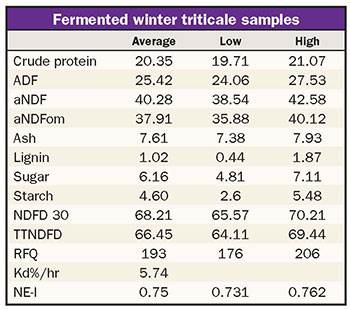

Forage quality, if managed properly, is some of the highest we can mechanically harvest in our region. The table shows the range and average of fermented samples from one of our trials. The improvements in management easily reach 18 to 20 percent crude protein with proper nitrogen and sulfur fertilization. Both protein and digestibility were found to be dependent on timely cutting. Initial research under Quirine Ketterings at Cornell University found winter triticale loses quality slightly slower than rye or wheat.

The big jump in acres has come about because the New York Farm Viability Institute invested in multiple years of research for managing this forage crop. Yes, there is a ton of research out there on growing winter grains — for grain. There was some research on growing them for cover crops to be killed in the spring.

What our work has found is that the strategies for growing high-yield, high-quality winter grain for forage is completely opposite to that for grain. Steps for an adequate cover crop fall short when optimizing winter grains for forage. Using best management practices with winter forage results in a cover crop on steroids. You magnify all of the cover crop benefits plus harvest several tons of very high-quality profitable forage.

Plant earlier in the fall

The biggest key we have found for moving the yields up in Northern climates has been to plant earlier in the fall. A minimum number of heat units are needed before tillers start to develop. More tillers mean more stems to harvest as forage the next spring.

A planting date of 10 days to two weeks before the optimum wheat planting date boosts yields 20 to 30 percent on a consistent basis in multiple trials. On-time fall planting gave us a week earlier harvest the next spring; this was a critical yield gain for both crops in double crop systems.

More tillers result in a thicker stand that can help smother winter annual and biannual weeds. The thick stand is a complete blanket to protect the soil from erosion throughout the winter and early spring. With zone/no-tillage after harvest, the stubble protects on into the following crop.

We found that planting more seed does not make up for planting late. You would have to raise the seeding rate 4.5 times to equal the tillering from on-time planting. Our on-going research has found that seed treatments are more important than increasing seed rate to boost fall growth and spring yields.

Given the fall, winter, and spring climate in the Northeast, most of the available nitrogen left over after harvest of a main summer crop is lost before planting the next spring. Our work has found timely planting of a winter forage will absorb that nitrogen (plus other available nutrients) and convert a potential pollutant into protein for your cows.

Fall nitrogen also bumps up the number of tillers and thus elevates the yield potential the next spring. The more tillers/biomass, the more nitrogen that can be stored. Capitalizing on Ketterings’ work, our ongoing research has found fall manure both supplies nitrogen and saves it as an environmentally safe “green” manure storage over the winter for use the next spring.

The 2016-17 winter crop, with 4,000 gallons of manure incorporated before timely planting, stored 123 pounds of residual and manure nitrogen in the biomass over the winter. Early research results have found this is often enough to meet all the forage yield needs the next spring but will not support the crude protein of 18 to 20 percent that we strive for.

Choose improved varieties

A large number of farms are still using common winter rye. This has not been the best result in our research as it yields 25 to 35 percent less than improved varieties of winter triticale in side-by-side tests. In our nitrogen trials, the rye frequently lodges at 50 pounds of nitrogen or more while the triticale has stood at 200 pounds of nitrogen per acre. Sufficient spring nitrogen and sulfur arecritical for harvesting high-protein forage. We have the new hybrid rye in our trial this winter to see how that will compare in forage yield, quality, and standability. Farmers grow improved varieties of corn, why not choose improved varieties of winter forage?

Active breeding and selection of winter triticale has resulted in varieties that yield 18 percent more than the old ones. If planted correctly, it will be ready nearly as early as rye. Triticale had a reputation of not being winter hardy. Correcting the poor management practices has it successfully overwintering into Canada.

The remaining residue after harvest, with its massive root system, effectively controls erosion well into the establishment of the summer corn silage crop. It is especially beneficial on heavy lake-laid soils with poor permeability. Research found winter forage stubble improves the air and water movement through the surface sevenfold. Thus, the benefit continues through the next crop if a strip till system is used.

The bottom line from multiple farms implementing intensively managed winter forage programs has convinced us that this is a crop for today’s farms. Not adding it to your program is leaving money on the table.