The dramatic climb in the use of winter grains for very high-quality forage, which also protects the environment in a sustainable manner, has opened a new forage rotation window of opportunity.

Winter forage such as triticale comes off at the beginning of haylage harvest. Planting into the resulting stubble saves time and soil, and enhances soil structure, while building soil health and organic matter.

All winter grains are allelopathic, releasing a chemical that inhibits the establishment and growth of grasses, corn, sorghum, and many weeds. Directly no-tilling corn (or sorghum) into the stubble of winter rye, winter wheat, winter triticale, or winter barley can be problematic. The winter forage’s allelopathic properties reduce both the percent of corn plants established and the vigor of those plants.

Yet, the benefits, especially on heavy soils where the stubble plays a key role in keeping the surface from sealing over by machinery tires or raindrop impact, are not something to lightly ignore. Research has found the intact stubble on the surface improves the permeability of clay soils sevenfold. This both reduces erosion and increases the moisture available to grow a high yield or enhance survival of small seedlings.

Make it work for you

Dairy and livestock farms grow more than just corn. When life gives you lemons (allelopathic compounds), make lemonade (put those compounds to work). Our ongoing work has discovered a completely new wrinkle in a rotation that utilizes the above benefits of winter forage residue and puts the allelopathic effect to work for you.

Legumes such as red clover, alfalfa, and soybeans are not apparently affected by allelopathic compounds. Directly no-tilling legume seedings into the postharvest stubble gives us all the soil enhancing benefits while resulting in better stands than early spring planting. It also moves the task from early spring crunch time until after first cutting of haylage.

Many farms are reluctant to put in legume seedings due to the effort and the risk for what often is half of a normal crop yield from those acres that year. Adding to that reluctance is the knowledge that on the first nice day in spring, the farm fieldwork is already a week behind. On the second nice day, it’s two weeks behind as they try to work ground and plant seedings, spread and incorporate manure, and prepare for corn simultaneously.

Utilizing winter forage as a platform for better seedings means moving all the seeding workload out of spring to the middle or end of May (for the Albany, N.Y, climate zone), after first-cutting haylage is harvested. This system raises the seeding acreage’s annual total yield of winter forage plus the new legumes to that of an established stand. It also has major benefits that improve the success of establishing the profitable hay crop.

A smooth start

The sequence is to establish the winter forage into a smooth, rolled seed bed the previous fall. Remember, you are going to be mowing it for the next four years, so don’t just throw the winter forage in rough fields like you might a cover crop. In the spring, the winter forage is fertilized and 2 to 4 tons of dry matter are harvested just before the start of the haylage harvest. The farm then continues with the rest of the haylage harvest as that is the most profitable decision at that time of year.

In late May or early June, after haylage is made, the stubble is sprayed with a high rate of water plus a low rate of glyphosate to stop any late-elongating winter forage tillers. It also controls any weeds that weren’t affected by allelopathic compounds. After an hour of drying for the spray, a no-till drill plants the alfalfa, red clover, or soybeans directly into the stubble.

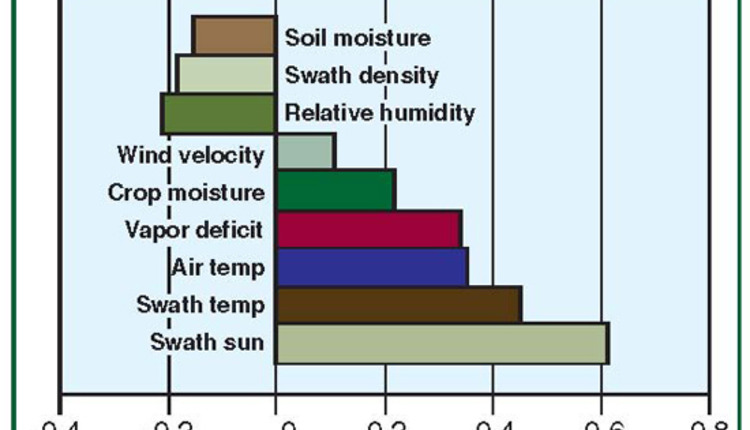

This system has a number of benefits to the success of the seeding. The most critical appears to be in keeping the drying wind 2 to 3 inches off the soil at the top of the stubble (see photo). This allows the soil surface, where the small seedling is struggling to establish, to remain moist. A number of farmers in the western New York drought of 2016 reported that their legume seedings in winter triticale stubble kept on growing right through the dry conditions. The stubble also captures runoff and channels rainfall into the soil surface to continue to feed the seedlings.

Seedings in bare, finely worked soil are extremely vulnerable to washouts from heavy rains. The stubble and the massive root system under the harvested winter forage crop is an outstanding system to protect the soil while the legumes are establishing.

John Knop of Canandaigua, N.Y., reported that last year he seeded 60 acres of conventionally tilled alfalfa and 50 acres of no-till alfalfa into harvested winter triticale forage stubble. His farm was hit with a tremendous downpour shortly after.

The conventionally tilled fields had gullies, washouts, rocks, and obliterated seedlings. It needed to be completely reworked and replanted. Meanwhile, his 50 acres planted no-till into winter triticale forage stubble came through unscathed and is a beautiful stand.

Less herbicide needed

As the legumes are planted into warm soils, they jump out of the ground and grow quickly. Without the soil being disturbed, the weeds that could have grown through breaks in the winter forage allelopathy are controlled by the herbicide before planting. We have had no need for a postemergent herbicide. For an organic system without the herbicide, we suggest no tilling the legume as soon as the winter forage is harvested.

We usually get at least one good legume cutting to add to the winter forage already harvested. As you move farther south, a second or even third legume harvest could be made.

The jury is still out on the ability to plant legumes with a companion grass. There is some indication that the winter forage allelopathy will not allow them to establish (allelopathy does not affect legumes). Until research shows otherwise, we plant just the legume (alfalfa or red clover) and after the first legume cutting in early August, no-till the grass into the stand as allelopathy effects would have dissipated by then.

Double cropping winter forages balances the spring workload, creates better seedings that don’t wash out, and the total seeding year can yield equal to full stands. These attributes make this an attractive change for today’s dairy.