Winter grains, primarily winter triticale or winter rye, are growing in popularity. With management backed by research, yields have moved from 1.5 to 2 tons of dry matter (4.3 to 5.7 tons of silage per acre) to 3.25 to 4.25 (9.3 to 12 tons of silage per acre) on New York farm fields. Quality is very high with protein reaching 18 to 20 percent and energy levels approaching that of corn silage.

With any forage harvest, there is many a slip between the cup and the lip. The quality you have when you start harvest needs to reach the mouth of the cow. From replicated trials, on-farm experiences, and mistakes, we have learned the key steps to realizing this quality from winter forage.

The first is to harvest at peak quality. The traditional boot stage with the head nearly out was fine when a cow produced 12,000 pounds of milk per year. Now we are pushing 30,000 pounds per cow, and forage quality needs to support that level.

Harvesting at flag leaf, when the last leaf is completely unrolled yet the head is still in the stem, is now the optimum maturity. Harvesting earlier while there is still a leaf rolled up and emerging (Stage 8) does not give any significant quality advantage and imposes a yield reduction of around 35 percent in our trials. Of course, being at Stage 8 and facing a week of warm weather and rain, harvest what you can if you are needing forage for the high group.

The timing of flag leaf depends on the species used and the date of planting. Rye is earlier than triticale, but new forage triticale varieties can be nearly as early as rye and higher yielding. Planting at the optimum time, two weeks before your climatic zone wheat planting date, will give a week earlier harvest the next spring. Triticale will lose quality at a rate slightly less than wheat or rye.

The exception to the above harvest stage occurs when temperatures, especially night temperatures, drop to 40°F or below. The cold nights both conserve the energy produced by photosynthesis during the day and reduce the physiological maturation, so it maintains fiber digestibility. Thus, under these conditions, the winter forage could be harvested at a slightly more mature physical stage and still meet the quality needs of high-producing cows.

Wide enough to dry

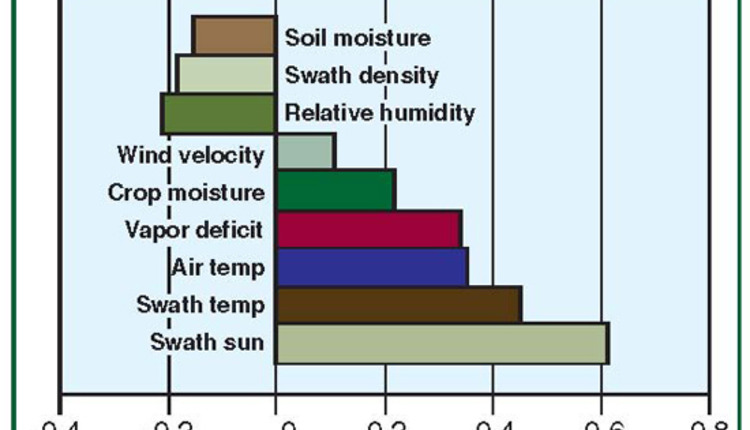

A wide-swath, same-day haylage harvest system is critical to capturing the very elevated sugars and plant starches in the forage cell. By laying the swath at greater than 80 percent of the cutterbar width, more of the forage is exposed to the sun. Cut plants exposed to sunlight continue to produce carbohydrates through the combination of carbon dioxide and water in photosynthesis until whole plant moisture drops below 60 percent. This photosynthetic activity dries the crop faster than any machine manipulation can accomplish.

Yes, you are driving on the crop when swaths are greater than 80 percent of the cutterbar width, but it has little negative effect, especially if the mower is set to cut at the proper height. Using this harvest system, farmers have been able to ensile greater than 35 percent dry matter silage the same day that they mowed it — as long as the sun shines.

If the swath is less than 80 percent of the cutterbar width, you are in fact compost drying the crop windrow. Mowing into windrows or leaving the crop overnight burns off most of the sugar and starch, lowering the energy of the forage and elevating the risk of clostridia and butyric formation. The only exception is if the night temperatures drop below 40°F, which reduces or stops respiration energy loss.

Our research found that conditioning is counterproductive in making hay crop silage as it breaks the stem, preventing capillary action from drawing the water to the photosynthetically active leaves from the entire plant. We also found with tine conditioners there is serious leaf stripping on winter forage, which can reduce the quality. If your mower is not able to lay a swath greater than 80 percent, tedd immediately after mowing to maximize photosynthetic drying.

In spite of laying the swath at greater than 80 percent, you still may need to tedd. Dry matter of winter forage is often two to three times more tons per acre than a high-yielding first-cut alfalfa. The heavy crop comes out the back of the mower and lands with a splat. It only dries on the top layer. Lifting and spreading the crop two hours after mowing greatly accelerates the rate of drying.

Wide swath crops dry from the stem to the leaves. As the leaf is last to dry, it greatly reduces the chance of leaf loss from tedding. If the forage exiting the mower hits any deflection shield or tarp, our research has found this is a huge negative for rapid drying. The material impacting on the deflector/tarp creates a lump which, when it drops to the ground, does not dry.

Leave the ash behind

Because of the clear benefit from tedding, we suggest setting the mower to cut at least 3 inches off of the ground. In wide swathing, with or without tedding, you will need to merge or rake the material back into a windrow. Cutting shorter than 3 inches will only raise the ash content. The use of twisted rather than flat knives will also suck up and incorporate more soil in your forage.

Dirt in the forage does not produce milk. Charles Sniffen, a world recognized dairy nutrition authority, found a 2 percent ash level jump in haylage being fed in a 60 percent forage diet directly reduced the milk produced by 1.9 pounds per cow per day. Mowing at the 3-inch level and setting the rake/merger to the top of your work boot will collect nearly all the forage with minimal soil incorporation.

Watch the forward speed of the merger. Many farms run them faster than the machine was designed. This both jams the winter forage into the tine slots in the front of the machine and moves the pickup point from the front of the machine where the tines are lifting to directly under the machine. At that point, the tines are moving opposite to the direction of travel and as a result drags the forage forward into the dirt.

We suggest setting the chopper to cut at least 3/4 inch and preferably at 1-inch length. Timely harvested winter forage is like brown midrib (BMR) corn silage in that its rapid degradation in the rumen tends to have it wash out to the gut before the necessary extent of digestion. The other advantage of longer cut that we have seen is with winter forage harvested wetter than optimum. Our replicated research clearly found that longer length of cut greatly reduces the amount of leachate generated.

The right bacteria

We highly encourage the use of an inoculant. This is a no brainer. You are producing a very highly digestible forage with lots of sugar. Why let any random bacteria or fungi grow in it just to save a dollar or two?

Limin Kung of the University of Delaware recommends a homolactic bacterial (no buchneri). Some companies produce homolactic bacteria specifically for high sugar, higher moisture crops such as winter forage.

Winter forage is some of the highest quality forage we can make. It can support high milk production with high components, if that quality makes it to the mouth of the cow. Following the best management practices will go a long way to assuring that the forage you grow and harvest will produce milk from your cows.