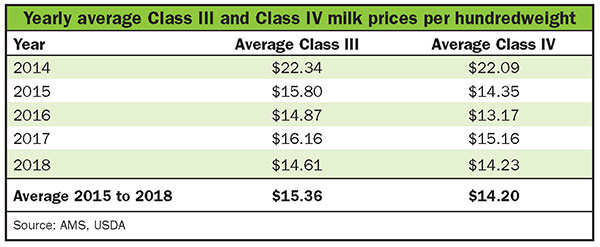

The Class IV price for butter and powder averaged $14.23 for 2018, the second lowest for the past four years. The lowest Class IV average was $13.17 for 2016. Overall, the Class IV price averaged $14.20, $7.84 lower than the record $22.09 Class IV price for 2014.

dairy marketing specialist at the

University of Wisconsin-Madison.

RESHAPING THE INDUSTRY

The trend of fewer and larger dairy herds will continue regardless of the price of milk. When older dairy producers decide to retire, and if there are no family members interested in taking over the operation, the dairy often exits the industry. Also, many of these operations are small herds with outdated facilities. They would require significant capital expenditures to modernize and expand to economically justify modern labor-saving technologies like milking parlors or robots.

The number of licensed dairy herds declined 30.6 percent from 64,540 in 2005 to 44,809 herds in 2014, an average annual decline of 3.4 percent. The biggest loss was 3,010 herds between 2011 and 2012, and the fewest herds lost was 1,225 between 2014 and 2015, which followed record-high milk prices in 2014. During this time period, the average herd size increased from 140 cows to 207 cows by the end of 2015.

Low milk prices for the past four years have created a lot of financial stress on dairy producers, resulting in more than a normal number exiting dairying. From 2014 to 2017, the number of dairy herds declined by 4,590 to 40,219 herds, a 10.2 percent reduction, which also was an average annual decline of 3.4 percent. The average herd size climbed to 234 cows by 2017.

Individual states have been reporting that after four years of low milk prices, the reduction in herds accelerated throughout 2018. We will know the full impact in February when USDA releases the number of licensed dairy herds for each state for 2018.

For example, on January 1, 2014, Wisconsin had 10,541 licensed dairy herds. By January 1, 2018, that number had declined by 1,740 to 8,801, a 16.5 percent decline for an average annual decline of 4.1 percent. By January 1, 2019, Wisconsin herds had dropped to 8,110, a loss of 691 herds since January 2018 for a 7.9 percent decline.

RELIEF IN SIGHT?

Dairy producers need much-improved milk prices in 2019 to heal balance sheets. But will milk prices be better, and if so, by how much?

The answer depends upon the level of milk production, domestic dairy product sales, and dairy exports. USDA’s December outlook forecasted milk production to grow by 1.3 percent in 2019 from an average of 20,000 fewer milk cows than 2018, being more than offset by 1.5 percent more milk per cow.

Normally, assuming good domestic sales and dairy exports, a growth in milk production well under 2 percent would be positive for milk prices. The forecasted growth in milk production could turn out lower. We can expect a continued decline in dairy herds, which could reduce cow numbers even more.

Wet weather in the spring and fall of 2018 also reduced the quality of forages and the resulting silage inventory, particularly in the Northeast and Midwest. This could dampen growth in milk per cow.

U.S. SALES COULD GROW

Domestic sales are forecasted to grow modestly in 2019. While the growth in the economy may be slower from that of 2018, the relative strength should support continued growth in domestic demand. Low unemployment and higher wages will put more money in consumers’ pockets. Both the Consumer Confidence Index and the Restaurant Performance Index are higher, which indicates growth in sales.

While fluid (beverage) milk sales will likely continue a downward trend, butter and cheese sales are expected to climb. With about 58 percent of milk production now utilized to make cheese, this should bolster total milk sales. So, domestic sales should also be positive for milk prices in 2019.

But much uncertainty for 2019 milk prices lies with dairy exports. Unless the unresolved trade conflict with Mexico and China ends early in 2019, we can expect dairy exports to be lower than 2018. Retaliatory tariffs imposed on cheese by Mexico and most dairy products by China have negatively impacted exports.

U.S. negotiations with Mexico and Canada to replace NAFTA resulted in the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Canada agreed to eliminate their Class 6 milk price. That product category put the price of their skim milk powder and milk proteins well below the U.S., virtually eliminating the ability of the U.S. to export milk proteins to Canada.

Canada also will eliminate Class 7. This allowed Canada to export nonfat dry milk at prices below that of the U.S. But, Canada will base the price of nonfat dry milk off of U.S. nonfat dry milk price minus a rather large make allowance (the plant cost to make the product), which will still give Canada a competitive advantage in exporting their nonfat dry milk.

Canada also agrees to allow for a modest increase in market access over six years, and thereafter additional access by 1 percent per year for 13 years. Until the U.S. eliminates its tariff on Mexico steel and aluminum, Mexico will not eliminate its tariff on U.S. cheese.

The U.S. Congress, the Canadian Parliament, and the Mexican government still need to approve this agreement sometime in 2019. So, USMCA may provide no or only limited benefit to exports in 2019.

A stronger U.S. dollar also will not help exports. But, there are other factors to support dairy exports. The growth in world milk production will slow in 2019. The combination of higher feed prices from a summer drought and low milk prices has dampened the growth in EU milk production, the largest dairy exporter.

A drought also has reduced feed supplies in Australia, reducing cow numbers and milk production. New Zealand’s milk production has been running 6 percent higher than a year ago in recent months. A possible return of drought conditions could slow New Zealand’s milk production later in 2019.

The slower growth in world milk production will raise world dairy product prices and open up opportunities for U.S. dairy exports. Some of the reduced exports to China and Mexico could possibly be replaced by greater sales to the Middle East/North Africa, Southeast Asia, Japan, and South Korea.

THE 2019 FORECAST

A growth in milk production of no more than the forecasted 1.3 percent and modest growth in domestic sales will support higher milk prices. A level of dairy exports, while less than the 16 percent of U.S. milk production on a total solids basis in 2018, could still support milk prices. USDA’s December forecast, and most other industry forecasts, are not overly optimistic on the extent of the improvement with 2019 milk prices — averaging no more than $1 per hundredweight higher than 2018.

But milk prices are very sensitive to relatively small changes in milk production, domestic sales, or dairy exports. So, there is a real possibility milk prices could turn out better, particularly if milk production ends up lower than current forecasts.

Class III forecast: As of now, I could see the possibility of the Class III price starting the year below $15 and then hitting that mark by the end of the first quarter. It could be in the high $15s by the end of the second quarter, the $16s in the third quarter, and high $16s in the fourth quarter, averaging about $16 for the year compared to the estimated $14.61 for 2018.

Class IV forecast: The Class IV price may be in the high $14s for the first half of the year, and then in the $15s for the remainder of the year, averaging about $15.30 for the year compared to an estimated $14.23 for 2018.

No doubt milk price forecasts will change monthly as milk production, domestic sales, and dairy exports are better known. Dairy producers need to follow changes in forecasted milk prices and consider using one or a combination of the following price risk management tools: Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) recently passed in the 2018 Farm Bill, Dairy Revenue Protection, LGM-Dairy, forward contracting with their milk buyer, or using dairy futures and options.