The author is a professor emeritus and dairy marketing specialist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

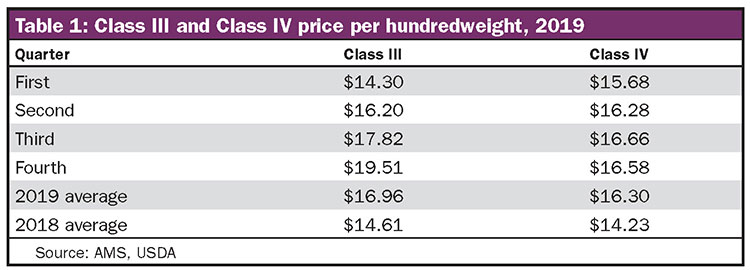

After 4-1/2 years of milk prices below the cash cost of production for many dairy producers, profit started to return during the second half of 2019. Class III prices were a low of $13.89 in February and averaged a paltry $14.30 in the first quarter (Table 1). Cheese prices started to improve by the second quarter and into the fourth quarter. By November, Class III hit $20.45 . . . the first time above $20 since November of 2014. That lifted the fourth-quarter average to $19.51. Class III averaged $16.96 for the year, $2.35 higher than 2018.

Higher milk prices were propelled forward by relatively smaller growth in production and improved total milk sales. Milk cow numbers averaged 0.7% lower for the year, and milk per cow was 1.2% higher. That netted just a 0.5% gain in 2019 milk production.

Beverage milk sales were 1.8% lower through October, but cheese sales were about 1.5% higher. With beverage milk accounting for about 25% of milk use and cheese for more than 50%, higher cheese sales more than offset lower beverage milk sales, increasing total milk sales.

Despite the continued trade war with China, dairy exports through November were still equivalent to 14.5% of milk production on a total milk solids basis. Year-to-date total whey product exports were down 20% from a year ago due mainly to 53% less exports to China as a result of retaliatory tariffs and African Swine Fever that reduced the size of China’s swine herd.

Overall, cheese exports were 4% higher with improved exports to Southeast Asia, South Korea, and Mexico. Nonfat dry milk exports were down 5% but came on strong, as exports were 25% higher in September, 17% higher in October, and 41% higher in November. Butterfat exports were 67% lower.

Sustainable momentum?

The question is can the much-improved milk prices from the last quarter of 2019 continue into 2020?

The answer depends upon how the level of milk production, milk sales, and dairy exports differ from what happened in 2019. Historically, dairy producers respond to higher milk prices by producing more milk.

The Class III price was as high as $20.25 in 2008 and averaged $17.44 for the year. But in 2009, the Class III price was as low as $9.31 and averaged just $11.36 for the year. Dairy producers experienced equity loss, many exited the business, and milk production fell 0.4%. But milk prices recovered rather quickly, with Class III reaching $14.98 by December 2009 and then averaging $16.26 in 2010 and $20.14 in 2011.

Dairy producers responded by collectively raising milk production 1.9% in 2010 and another 1.9% in 2011.

I don’t see higher milk prices resulting in a similar production response in 2020. The difference is dairy producers have experienced low and unprofitable milk prices for not just one year but for 4-1/2 years. Producers lost much more equity this time around. Dairy producers need to strengthen their balance sheets before considering dairy expansions.

A bad feed year

Further, a very wet 2019 lowered the quality of alfalfa hay, haylage, and corn silage, which will likely dampen gains in milk per cow.

With the balance between sexed semen and producers breeding lower-producing cows and heifers to beef, the number of dairy replacements is down. With higher milk prices, lower-producing cows may now still be profitable and some producers may keep them in the herd longer to produce all the milk they can.

Depressed milk prices resulted in more than the normal number of dairy producers exiting the business in both 2018 and 2019. When dairy producers exit, many of the cows are bought by other producers as replacements rather than expanding the herd. With higher milk prices, the number of dairy producers exiting will likely slow in 2020 but remain at a relatively high level.

USDA is forecasting a 1.7% growth in 2020 milk production from just 5,000 more cows but a 1.7% gain in milk per cow. I won’t argue with the number of cows, but with the forage quality issues, I think the gain in milk per cow is on the high side. I could see milk production growing more like 1.3% to 1.4%.

Things look good for continued dairy product sales to consumers. The economy is expected to show good growth, unemployment is low, wages are higher, and consumer confidence is positive. While beverage milk sales will likely continue on the downward trend, this situation will be more than offset with higher cheese sales.

Higher dairy exports are a real possibility for 2020. World milk production, at least for the first half of the year, may inch up less than 0.5%. Milk production of leading dairy exporters has been either lower or up less than 0.5%.

A major drought in the EU limited feed supplies and raised feed prices. The number of milk cows was reduced. Milk production was up just 0.5% in 2019 and is forecasted to be up less than 1% in 2020.

New Zealand’s production was down 1% in 2019 and is forecasted to be up no more than 1% in 2020. Australia has been under a severe drought resulting in contracting cow numbers and reducing production 5%. The forecast is for 2020 production to be down another 2%. Weather issues reduced Argentina’s production 1% in 2019 and is projected to be up less than 1% in 2020.

The U.S., the third major exporter, behind New Zealand and the EU, will have the largest improvement in milk production among all major exporters at more than 1%. The major export countries will have fewer dairy products to export, opening up opportunities for the U.S. Dairy product prices in the U.S. have been higher than world prices. Further world prices will increase and U.S. prices fall making U.S. more price competitive. But, with the other major exporters having less products to export, importers will turn to the U.S. for dairy products.

Hone in on trade

Any trade agreements will have little impact on 2020 dairy exports since it takes time to phase them in. The U.S.-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) trade agreement was passed by the U.S. Congress. Phase one of the agreement with China has been completed, which could possibly increase exports of whey products in 2020 as China attempts to build back their swine herd. Phase one trade agreement has also been reached with Japan, but the impact also will not be felt until after 2020.

USDA is forecasting 2020 exports to increase 3.3% on a fat basis and 5.3% on a skim-solids basis. But, there is some caution on the demand side as many economic organizations have projected the possibility of a global recession in the second half of 2020. China posted its weakest year-on-year global domestic product (GDP) growth in 30 years through the second quarter of 2019. Similar challenges face the EU.

As I write this outlook, I am a little concerned by how much cheese prices fell the last half of December. At the beginning of the month, cheddar barrels were $2.265 per pound and fell to $1.61. The 40-pound cheddar blocks fell from $1.9475 per pound to $1.77. But, prices recovered some by the end of December, and I am counting on additional price recovery. Cheese stocks are lower than a year ago and sales are favorable.

Prices could strengthen

If the growth in milk production is no more than 1.5%, cheese sales continue to grow, and exports are higher, the price of butter, cheese, and dry whey should all strengthen. Nonfat dry milk prices are now well above $1 per pound, and with exports forecasted to be higher in 2020, prices should hold above $1.

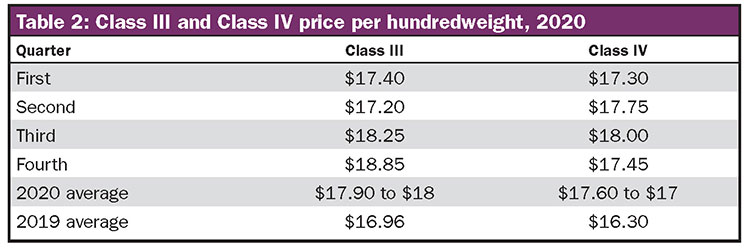

Class III will average higher than 2019 for the first three quarters but could be lower for the fourth quarter. Compared to 2019, Class III could average about $17.40 in the first quarter, more than $3 higher; about $17.20 in the second quarter, $1 higher; about $18.25 in the third quarter, 45 cents higher; but about $18.85 in the fourth quarter, 65 cents lower (Table 2).

For the year, Class III could average $17.90 to $18, 85 cents to $1.15 higher than 2019. With expected higher nonfat dry milk prices above $1 per pound and butter averaging more than $2 per pound, Class IV could net $17.60 to $17.70, $1.65 higher than 2019.

In early January, Class III futures did not invoke optimism, especially for the second half of the year, but Class IV futures were more favorable. USDA forecasts Class III to average $17.35 and Class IV $16.90 for the year. But because milk prices are so sensitive to rather small changes in milk production, sales, or exports, these projections can easily change.

No doubt all forecasts will be modified as we move through the year and we see what actually develops. The bottom line is milk prices will be much improved over prices from 2015 through the first half of 2019.