It is an emotion-filled and polarizing fight over money. The focus is California’s $1.15 billion of milk market pool quota — at least that’s what its value was last year — and a petition drive that is underway to eliminate all of it.

That by itself shouts volumes about how intense, sensitive, and unusual the issue is. It is also why I decided not to quote anyone in this article. Every person I talked to — producers, an industry association leader, a co-op official, a dairy broker, an economist, and an accountant — was willing to share their thoughts, but not their name or affiliation. Here is what they told me:

There are approximately 2.15 million pounds of pool quota solids in California, all of which was given to the state’s roughly 2,700 Grade A producers by the State of California beginning in 1970. None has been issued, though, since the 1991 to 1992 new growth allocation period.

The price premium that goes with quota, which today varies from $1.43 to $1.70 per hundredweight depending upon region of the state, was an incentive to help ensure that Class I market demand would always be met. It was a key part of the Statewide Pooling Program that was overwhelmingly voted in by producers in 1969.

Another key feature was a manufacturing make allowance that gave companies an incentive to build processing plants in the state — which they did enthusiastically. Their demand for milk gave dairy producers the opportunity to grow if they wanted to, and by 1994, it made California the biggest milk-producing state in the country. Twenty-five years later, it still is.

Everyone had a choice

Some producers grew by selling all of their quota and buying cows. Some decided to not expand at all so they could continue to have a high blend price. Some have made regular purchases of additional quota to keep up with per-cow production gains, or because their location gave them no other practical way to enhance revenue. Many were in between. Then, and still today, it was an individual choice that each producer made for themselves.

A higher price for quota milk meant quota immediately took on significant value and demand among dairy producers — demand that has been constant ever since. A big reason is because the higher milk price allows quota to pay for itself over time. In recent years, the payback period has been about seven years.

For many producers, quota has also been the largest, most quickly liquid asset they will ever own. Thus, it has been a lifesaving safety net during financial crisis that helped strapped farms stay in business. Or allowed them take advantage of big financial opportunities. For many producers, it has also been their retirement plan.

Over the decades, quota has been so saleable and so coveted that almost none of the 2.15 million pounds is still held by the original owners. Market prices for it have always risen and fallen along with milk prices and the dairy economy, but they have tended to be very stable. For instance, for 50 straight months between 2014 and mid-2018, average monthly transfer prices reported by the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) were never under $500 per pound.

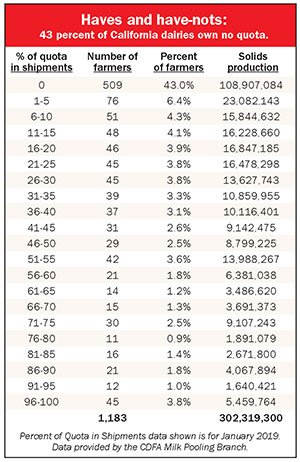

As California milk producers died, retired, moved to other states, or otherwise went out of business, the number of quota owners has steadily declined. “Percent of Quota in Shipment” data for January 2019 from CDFA (see table on facing page) showed that of the 1,183 Grade A farmers in the state, 509 (43 percent) had no quota at all.

That means the 674 who do own quota own an average of 3,190 pounds each. Some have far less, but some have spectacularly more.

Money to pay the quota milk price premiums had always come out of the Class I pool; everyone contributed, including those who didn’t own quota. But the cost was essentially invisible, because it was blended into the pool and was not listed as a deduction on milk checks.

All of that changed in November when California entered the Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) system and settlement checks began showing the deduction for each farm. That’s when the civil war began.

Quota sales prices, and thus producer equity levels, began weakening in August (for transfers that took effect in September). People I spoke to at the time agreed it had much more to do with four years of low milk prices and terrible margins than it did with joining the FMMO system.

As seen in the table above, significant price declines continued in September, October, and November — then prices fell off a cliff in December (for transfers taking effect in January 2019). That one-month plunge of $119 was by far the biggest in the program’s 49-year history. The January, February, and March prices, by the way, are the three lowest averages in the 17 years of quota transfer data posted on the CDFA website.

The decline from December to March translates into $347,710 less equity for the average quota owner. From July to March the difference is $442,900. For large owners, however, the hit is many millions. Statewide, the total value of quota in March was 38 percent less than just eight months before. After four years of low prices, bad margins, and losing money, the timing is awful. It means everyone with quota has a smaller safety net and looks more risky to lenders.

The plunge in quota’s value coincides exactly with a petition drive started in December that backers hope will lead to a producer referendum to eliminate the program entirely, which is allowed to continue under California’s FMMO. The petition drive is called Stop QIP (the Quota Implementation Plan). Its petition signature form lists a P.O. box address in Visalia, an email, and a toll-free telephone number.

Just like before the FMMO was implemented, funding for QIP is paid by all Grade A producers, whether they own quota or not. The cost is approximately 38 cents per hundredweight. The difference now is, the cost appears as a deduction on milk checks, so every Grade A producer sees it. Stop QIP backers encourage producers to “do the math.”

A recent letter to me submitted by Stop QIP said, “With dairymen already struggling to pay all of theirs bills, this additional assessment or tax, whatever you want to call it, is just like pouring salt into the wound. A majority of dairymen put the program in place and a majority can take the program out.”

Petition backers say any dairy with 22 percent quota coverage or less pays out more to fund the program than it receives in quota premiums.

Enough signatures should be easy

Verified signatures from 25 percent of Grade A producers covered by QIP are needed for a petition to be submitted to the CDFA Secretary or the QIP Administrator. Since 43 percent of producers own no quota at all, that requirement seems like an easy one. However, because the petition and all signatures will be posted on the CDFA website for a minimum of 90 days, that might make some producers balk at signing and being public.

Several months of review, including evaluation by the state Producer Review Board, would follow. The board would make an action recommendation to the secretary, but the final decision whether to hold a referendum would be hers. Two things would be needed for “substantive amendment or termination” of QIP:

– At least 51 percent of all producers who are eligible to vote would have to cast ballots.

– Passage would require at least one of two super majority requirements to be met: either 65 percent or more of the voters who make 51 percent or more of the milk, or 51 percent or more of the voters who make 65 percent or more of the milk.

So, what did people tell me for this article?

“Emotions are already high,” said a producer in Southern California who owns several dairies. “Some people are acting selfishly, and it is causing a lot of hatred in the industry.

“A lot of people have forgotten why and how the quota program came into being. It was a system that protected dairies and allowed farms to expand beyond their quota base. The make allowance that was in the program for plants was the incentive to build processing capacity, and it worked fabulously for decades,” the dairyman continued.

“With the federal order, everyone shares in Class I sales, including people who don’t have quota. Everyone is paying to fund the program. People are getting the quota cost in their blend, then it comes out; there is no net loss. But all people see is a line item on their check, and they want to get rid of it.

“Emotions are so high. They need to simmer down before sensible discussion and compromise can happen. If quota were suddenly eliminated, tremendous banking turmoil would take over. Bankers are scared to death already. One bank doesn’t want to loan to dairies at all now,” he said.

“What is needed is for all parties to start talking, or else everyone will be hurt even more. This is a terrible financial climate right now, and this argument only makes things worse.

“California’s best years are over,” he added. “We’ve got some real icons in our industry who are hitting the ropes right now. The ones who are going to be left are the ones who have trees. If they just have cows, they are doomed.”

A producer in Central California who owns two dairies, one with no quota and one that has quite a bit, said, “This has already caused hard feelings between relatives. It has already hurt friendships. People have agreed it is a topic not to be discussed, yet it’s one that can’t be avoided.

“Ninety-five percent or more of the producers in California never knew they were paying for the quota system because it never showed up as a line item on their check. Now it does. That is where we are in a nutshell. And simple math will tell them — not to mention the people who are railing about it — how much they have been paying for 25 years that they never got a dime on, so people are going through the roof.

“The quota program was a decision that producers made. They all voted to put it in. And it was a decision that producers who sold their quota also made. Many guys back in the day decided they wanted to expand so they sold their quota and bought cows. It’s a decision they chose to make.

“I talked to a friend the other day who owns a fairly minor amount of quota in the scheme of his total operation. He said he decided to sign the petition because he hopes it will further the discussion that needs to happen between both sides,” he said.

A reaction to tough times

“There are guys who are really upset and there are guys who say, ‘They tried to stop it before. It didn’t work then and it won’t happen now.’ Well, I don’t think they are reading the tea leaves right this time. Now, 100 percent of the dairy producers in California know how much is coming off their checks. And when times are bad, dairymen always start looking for things to cut,” the producer said.

“Discussions about how to retire quota have been going on for decades,” he pointed out, “and a plan was even submitted to CDFA years ago. I am one who believes that as long as you have quota and overbase you will have a divisive issue.

“There has always been a big safety net aspect to quota, and it has long been looked at as a retirement annuity for farmers. Prices going down have hurt a lot of people. A broker told me yesterday that he couldn’t even get an offer at $300.

“If the quota program goes away then dairies will become riskier lending customers for banks,” he concluded.

Another Central California producer who sits on a high profile board said, “There’s people on both sides of the fence. I’ve really had to park my opinions because of my position representing both people who own quota and those who don’t. The only thing I can say is I think it makes sense for people on both sides to come to a sensible agreement, whatever that is. People need to sit down and talk.”

A regulatory expert for a large producer organization said, “There are those who would prefer that no changes ever be made to the existing program, and there are those who think change is appropriate. If you are open to change, the question becomes what kind of change and how fast? I am sure this conversation is going to last for some time.

“Right now, it is important to acknowledge that the milk pooling-pricing-quota systems that are currently in place are there because producers acted collectively to put them there. Changes have been made to these programs when enough pressure emerged to make them, but it was never a quick process. Our industry has faced these challenges before and has found solutions that most producers supported,” he explained.

An economist at another industry organization said, “Emotionally, there’s definitely a lot of concern out in the field by producers in terms of how long this downturn will last. As for the hit on quota, I think the mood might be partly driving that.

“I think the main concern currently has been discussions where some producers would like to get the Quota Implementation Plan eliminated. A petition has been circulating by a group that actually mailed a petition to every producer in the state, which is deeply disturbing for producers in California who own quota,” the person remarked.

“Every producer in the state pays into a fund that pays out the quota price premium. There is a point at which the return for quota is less than what a producer pays in. That number is approximately 22 percent quota ownership. What makes this reality significant is that as a result of now being in a federal order, the deduction for quota is now a line item on milk checks. Producers now know how much the quota program is costing them each month,” the individual said.

“I talked to a lot of bankers last spring because the milk price had been going up after being down for so long. Prices were looking up a little bit in spring so people were feeling a little optimistic, but then the trade war hit and prices kept spiraling down toward the end of the year,” continued the person.

“There are some bankers now who are feeling a little on edge in terms of where the industry is going. The dairies that stayed were not in a great position, but it didn’t seem like they were on the verge of closing the doors on folks. Now that the price is down even further I think those conversations are being revived. We’ve had a lot of our producers call and ask what can we try to do to get more money from our processors?

“It’s absolutely not a good time to own cows, and it’s hard to tell folks that,” the economist commented.

A dairy accountant said, “When the pooling law was written 50 years ago, it was never anticipated that quota would become a freely exchanged, highly valued asset. People can’t just take an old law that was never updated to the current market condition of that asset and simply receive an unjust benefit. So there won’t be a snowball’s chance the conversation is going to just disappear.

“What I’m hearing from banks is that dairies with high debt but have quota, they are just sitting back and being patient. But if you have high debt and no quota you are probably a 2 on their ‘worry about’ scale of 1 to 10.” (No. 1 would be of greatest concern.)

“What this petition has done is make people with no and low amounts of quota irate. Before they never realized the difference in price because they never saw it on their checks,” he continued.

“Do I think quota is going to go out? That’s not just a no, it’s a hell no. I really don’t think quota will go away all at once. There’s no way the state can write off $1 billion in asset value without having lawsuits coming at them from everywhere.

“I don’t think it’s going to be as easy to get rid of as the anti-quota people think, because I think a challenge back from quota owners would succeed. I think it’ll end up in some kind of a mediation room that would say, ‘Okay we will deem it over, but amortize it out so people will get paid back instead of having it written off at once.’ Then as soon as the payoff is done everyone is equal,” he said.

I saved the co-op official for last because his candor and impartial analyses have impressed me for years. This time was no exception.

“Some people are offended that this is being called a tax by the people who want to eliminate it.

“It is a very emotional situation, people are worried that the legislature could yank quota away.

“People who think they know how a referendum would turn out should remember the last presidential election. It proved anything can happen these days in an election,” he said.

“Both sides are at risk here, which should eventually lead to adult conversations on many levels.

“A ‘sunset’ idea that buys back all quota is one good idea. It isn’t right to have it go away suddenly, but this might lead to discussion on other options.

“The anti-quota people worry that the Producer Review Board might not pass it on to the secretary. They shouldn’t. At the board’s March 6 meeting, the general council for the secretary said she is not inclined to ignore a legally submitted petition, even if the board doesn’t pass it through to her. She said, ‘The secretary believes in self-determination by producers,’” the co-op official explained.

“If the petition does get enough signatures, it could lead to a broader discussion in the industry, or the proponents could withdraw their proposal and work together with quota owners to form a compromise bill. Or nothing may happen. Or there could be a ‘sunset’ plan of some amount of time during which quota gradually goes away.

“There are people behind this effort who weren’t willing to speak up before, but they are now because they see a potential path forward.

“Any plan that eliminates quota over time would put some dairies in a position where they would have to re-examine if staying in business pencils out at whatever the lower milk price number is.

“I believe that in this situation what Winston Churchill said about Americans during World War II applies to California dairymen: ‘You can always count on them to do the right thing after they have tried everything else,’” he concluded.

I don’t have a dog in this fight because I have never owned a cow. But after 42 years in the industry I do have an opinion:

This is perhaps a once-in-a-lifetime issue, so it deserves the most serious discussion possible. It is discussion that should be thoughtful and deliberate, not emotional and rushed. Producers deserve a solution that focuses on the future, not a reaction to the current situation. It needs to be as voluntary as possible, not forced. It needs to make the entire industry better, not just part of it. It’s a discussion that needs to start right now.