There is no doubt that genomics has made significant inroads with over 3 million dairy animals being tested in the past decade. However, the science of comparing DNA to observed and predicted animal performance could still do so much more.

To delve deeper into those ideas, Michael Lohuis, who heads up Research and Innovation at Semex Alliance, spoke about the issue during the National Genetics Conference held earlier this summer in Appleton, Wis.

Back to the report card

The next logical place to evaluate genomics is on-farm testing.

“It’s no surprise that 100 percent of the bull population is now being genomically tested,” he said. “There are 600,000 females tested per year, with an impressive uphill curve since 2008. There are 650,000 of the 4.2 million heifers born each year now tested, which accounts for 15 percent of the population.”

Lohuis says it could be a lot better, and one of the big reasons for testing is animal identification, particularly in large herds. “When these herds start genomic testing, they often realize animal ID was much less accurate than they initially thought,” he said. “Testing has the ability to sharpen identification and provide producers the opportunity to utilize their data in other areas, such as culling decisions.

“Genomics, as a tool, truly tells more about what you can do with your herd. Genomics can aid in selecting the best cows to use for in vitro fertilization (IVF) or a sexed program, whether they should get conventional or beef semen or be culled,” Lohuis said. “With the advent of sexed semen, there’s much more opportunity to use beef on the bottom portion of the herd.”

Overall, “on-farm testing” received a grade of C. This service has improved animal identification, but many farms are only using their genomic results as a tool for culling. On-farm genomic testing is still a tool that is sorely underused.

Inbreeding is on the rise

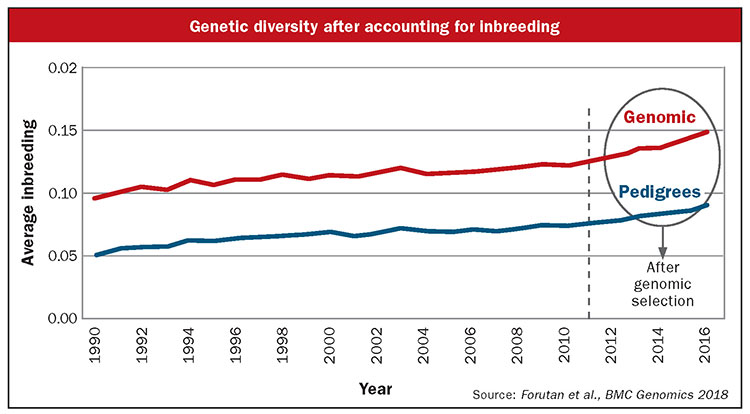

Genetic diversity is definitely becoming a growing concern among breeders industry-wide.

“When we started utilizing genomic testing as an industry, the thought was there would be more candidates for selection and that would improve diversity,” the animal geneticist said. “In theory, we should have been selecting animals from a lot of different families. That has not been happening, as the rate of inbreeding in general has almost doubled in the period of genomics,” Lohuis emphasized.

“Why do we continue to focus on so few families?” he asked. “Part of it is our expectations have gone up. There are so many bulls to choose from, and we have more traits, so now as farmers, we want to have a bull that has it all. The A.I. industry has responded by only selecting bulls that meet those exacting standards. So, we end up with fewer and fewer bloodlines, and this will be a problem in the long run.”

Lohuis explained that inbreeding depression can affect traits from fat yield to productive life, with up to 13 days of productive life lost per every 1 percent gain in inbreeding.

Is inbreeding always bad?

“In terms of science, it depends on which sections of the genome are homozygous. Before genomics, we looked at pedigree inbreeding but did not know if it was ‘good’ inbreeding or ‘bad’ inbreeding,” said Lohuis. “Inbreeding can have a negative impact, reducing fertility and production, creating higher probability of genetic defects and disease, and creating loss of between-family genetic variation — which ultimately reduces the potential for long-term genetic gain,” he said.

“On the flip side, inbreeding can create more uniformity in the best regions, ‘fix’ most desirable alleles, ‘purge’ most undesirable alleles, and create more potential for hybrid vigor in crosses.

“The question, though, is what are we sacrificing long term?” he remarked.

Overall, Lohuis gave genetic diversity a C minus. “There is still too much focus on too few bloodlines, and we know that inbreeding is increasing but cannot fully determine if it is a problem,” he said. “In the end, we are probably sacrificing too much long-term progress.”

Received a “D”

Understanding the genotype to phenotype relationship topic focused on identifying genotypes that change the phenotype.

“When we started down this path, we thought okay, this genomic tool is going to help us understand where all the genetic variation is coming from. What’s causing a bad trait?” he said. “As it turns out, maybe it’s a little more complicated than we thought.

“We essentially still have a ‘black box.’ We don’t necessarily know all the genes that are positive; we just have a very good tool for assessing the genome as a whole and coming up with a breeding value. We really haven’t improved on the black box approach yet,” he said.

Lohuis emphasized that the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) profile is just a start. “We still don’t fully understand the protein pathway variation. Nonadditive genetic variation is difficult to predict, especially as it pertains to heterosis and inbreeding depression,” he said. “Few additional causative mutations have been found.

“We have been able to identify some undesirable haplotypes, such as HH1 through HH6 in the Holstein breed, but the list is unimpressive for 10 years of work,” said Lohuis. There is still much more work to be done.

With that said, Lohuis graded this category a D, as genomics have overpromised and underdelivered. The genotype to phenotype path is very complex, but there have been some discoveries made for disease traits. Expect much more improvement in the category in the next 10 years.

Food matters most

The final category on the scorecard was meeting consumer expectations. In short, producing products that consumers value.

“Consumers expect safe and affordable food, and they expect it to be good for the environment. While higher productivity per cow is good for the environment, that may be something we as an industry have not communicated well,” he said. “Consumers want hormone and antibiotic free, no cruelty to animals, and more choice. They want taste, variety, locally produced, and the list goes on. We’ve been slow to recognize that consumer expectations have changed in the last 10 years and we need to do a better job responding.

“One of the things we have done very well is improve production efficiency for the environment,” he said. “We have better feed efficiency, as milk yield has increased faster than dry matter intake through the years. Dairy produces less greenhouse gas per kilogram of product produced than pigs and broilers. We can do a much better job talking about the improvements we’ve made in greenhouse gas emissions: We are down 31 percent from 1990 to 2012.”

In this final subject, Lohuis graded it a D minus. “Genomics has provided improved health and reproduction, but little effort has been exerted on direct value for consumers . . . with A2A2 protein being the exception. We have, however, made milk more sustainable, but that has been done unintentionally.”

The report card may not be all A’s, but Lohuis believes we should feel good about what we have done, and for the most part, genomics has been a rousing success. “In the future, though, we can do a much better job paying attention to consumers, considering the competition we face in the grocery stores,” said the big-picture geneticist.

The 10-year report card on genomics

Last issue: High grades on two fronts

This article appeared in the September 10, 2019 issue of Hoard's Dairyman.