There’s no doubt that inbreeding has been a topic heavy on dairy farmers’ minds as we’ve progressed through the genomic era. For that very reason, the cause and effect of inbreeding was a hot topic at the National Genetics Conference, held in coordination with the 2019 National Holstein Convention in Appleton, Wis. John Cole of USDA’s Animal Genomics Improvement Laboratory provided an in-depth look at the past 10 years along with a glimpse of how we may be able to manage future inbreeding challenges.

What is inbreeding?

“Admittedly, inbreeding is sometimes made out to be more complicated than it really is,” said Cole. “Inbreeding is simply mating animals that are related to each other. Inbreeding is something we can manage, but it is not completely preventable,” said the longtime dairy scientist.

When the science of genomics index surfaced in 2008, genotyping females became quite popular.

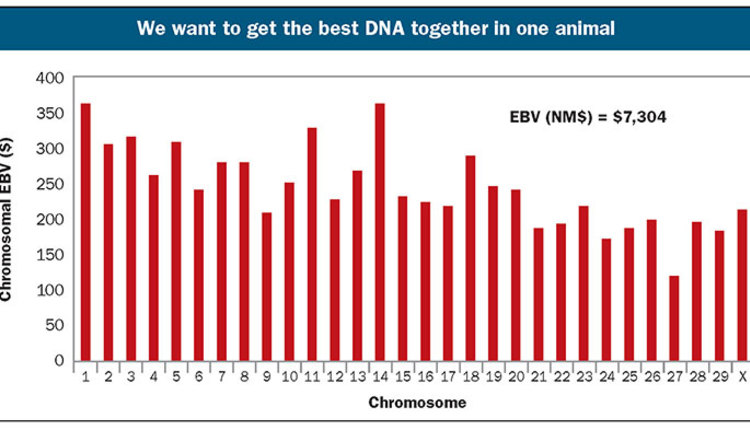

“This process allowed for added pressure in selection programs, giving us the chance to try and take the best DNA from the population and put it together in one animal,” said Cole. “In fact, genotyping has become so popular, the combined USDA and Council on Dairy Cattle Breeding became the first database with one million genotyped individuals in July 2015.”

Creating the best

“The principle behind getting the best DNA is this: We take the best Chromosome 1 in the population and match it with the absolute best Chromosome 2 in the population, and we do this with all chromosomes,” he said explaining information in the figure.

“We still have a long way to go, but the more pressure we put on trying to reach this point, the more we’ll be driven by mathematics and other considerations,” he said.

“This will lead to more heavy mating within certain lines, further driving inbreeding,” Cole commented. “I think you’re going to see a shorter generation interval on dams of bull sides.”

When it comes to making breeding decisions, genomics is helping us identify the best genes from the best animals. “At the end of the day, we are in a race that never ends,” said Cole. “Everyone is trying to find the high index bull (or female for breeders).”

Artificial insemination (A.I.) bulls are going to be bred to meet market demand.

“If demand in the market is for high index sires, that’s what A.I. companies are going to provide,” commented Cole. “If breeders are not willing to pay for less inbreeding, the market will not provide it. High genetic merit bulls have high marketability. Lower inbreeding rates (in most cases) result in slower genetic gains. As a dairyman, if you slow down, your competitors just get farther ahead,” said the Louisiana native.

“Who is willing to go slower in their genetic selection program to better manage inbreeding? Are you willing to watch neighbors and competitors go faster?” he asked.

The assumption has been that inbreeding is bad. Is that true?

“In a sense, it is true,” said Cole. “High levels of inbreeding are undesirable in the long run. We know that we have reduced fertility, reduced longevity, and reduced resistance to disease when we dramatically elevate the level of inbreeding in the population,” said the USDA scientist.

Why does this happen?

“When inbreeding levels rise, we’re more likely to pair two undesirable copies of a gene in the same location,” he said. “For example, in Holstein Haplotype HH1, when that gene is broken, the embryo dies and therefore affects fertility. The cow is bred, pregnancy is established, but then the embryo dies and the cow is back to the beginning. This mechanism is thought to account for most undesirable effects of inbreeding,” Cole said.

“There is also some data available stating that if inbreeding is used, but slowly, you can purge the harmful loci (get rid of undesirable loci). If you have purging, you can end up with long stretches of DNA that are homozygous for alleles you want,” said Cole. “The challenge is it’s difficult to do that effectively.”

“Hitchhiking often happens because inheritance happens on a chromosome. You’ll have a desirable stretch of DNA then an undesirable piece that’s close to it, so the undesirable locus gets dragged along (called hitchhiking), and that’s the cause we’re worried about,” commented Cole. “HH1 is the same kind of mechanism.”

There are many known recessives in U.S. Holsteins, and some are more desirable. The questions still linger, though — is the number of defects in our cattle population on the rise?

“Our team did a study on economic impact or loss, with a conservative $10.7 million in annual losses due to known recessives and mutations,” said the USDA scientist. The study was based on the economic impact as it affects fertility and perinatal mortality. Losses for each breed were calculated at $5.77 (Ayrshire), $3.65 (Brown Swiss), 94 cents (Holstein), and $2.96 (Jersey), respectively. Holstein losses were estimated at just under $1 per cow, spread over the whole population. This was based on figuring out when the loss occurred and the economic impact of the loss. Actual losses, however, are likely to be higher because there are more unknown loci.

The question still lingers — how much inbreeding is too much? The answer is yet unknown.

“We know it has harmful effects. Selection indices now include traits related to longevity, fitness, and health. It helps producers and geneticists avoid mistakes made in the past by changing selection objectives and not focusing solely on one or two traits.”

“When observing predicted transmitting abilities (PTAs) for the active Holstein bulls, if the inbreeding penalty for PTA for daughter pregnancy rate (DPR) is taken away and regressed on inbreeding, the relationship or correlation for DPR with inbreeding is negative,” he said. “Simply put, this means that as we inbreed more, we do have negative effects on fertility. This is not a surprise, but mere proof that it exists,” said the geneticist.

“Because we don’t know where this wall is, we may feel as though everything is fine and then cross a point of no return where we go from negative but manageable to very harmful and potentially unmanageable,” Cole stated.

How do we measure inbreeding?

“Pedigree inbreeding is based on the passing of chromosomes from parents to offspring over many generations,” said Cole. “An individual is assumed to have half of their DNA from their parents, one quarter from their grandparents, one eighth from great-grandparents, and so on.

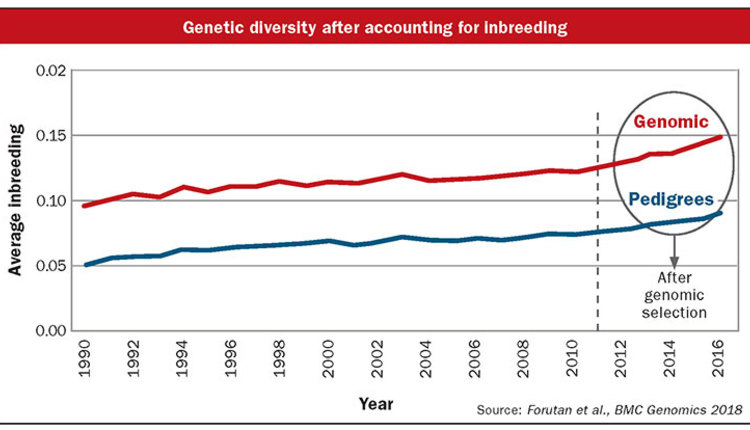

“With genomic inbreeding, we look at the genotype and not the pedigree to determine what genetic markers these animals have in common. Inbreeding climbs as pedigrees get deeper; however, the age of inbreeding may matter, too. If the inbreeding happened recently, there may have not been time to purge any harmful loci,” he said.

“Inbreeding is a property of an individual animal based on the DNA they have inherited. Expected future inbreeding (EFI) is a property of the population based on how related an individual animal is to the other animals in the population,” said Cole.

“For example, the Holstein bull O-bee Manfred Justice has an EFI of 10.4 percent because he has so many sons, daughters, and grandsons,” said Cole. “The more related a bull is to the population, the higher the EFI. Genomic future inbreeding (GFI) is based on the same concept.”

Evolving inbreeding levels

The EFI of cows is steadily going up. Some feel genomic inbreeding of young bulls is quite alarming. The trend may be worrisome, but their EFI is lower. That does not get us off the hook.

One bull of the past worth noting is Round Oak Rag Apple Elevation and his four-generation pedigree. “Elevation is actually less related to the population on average than expected,” said Cole. “When looking at a bull like Mara-thon BW Marshall-ET, he had a lot of sons and was terrible for daughter stillbirth,” Cole went on to say. “There was some stacking of Pawnee Farm Arlinda Chief and Walkway Chief Mark in his pedigree, and his genomic inbreeding was just shy of 9 percent, which is a little high.”

He continued, “When looking at Pine-Tree Acura-ET, a top young NM$ bull, his pedigree is very inbred. There is a full sibling mating on the maternal side, stacking up Mountfield SSI DCY Mogul-ET, and then on the sire side there is another full sibling to the two in the bottom half of the pedigree. This is a bull with 17 percent genomic inbreeding and 13 percent pedigree inbreeding. This is where we’re ending up in this race where there’s no end point.”

What do we do about it?

Scientists are trying to understand what has been lost through inbreeding. Early in the genomics era there was an effort by many companies to sample broader pedigrees, but people didn’t buy most of those bulls.

“In the U.S., we adjust PTAs for inbreeding to account for inbreeding depression,” noted Cole. “For the bull Acura, if we take away the inbreeding depression, his NM$ would be $1,282 versus his $1,065 (April 2019). Even after taking away nearly $300, he remains at the top of the list.

“Male genetic diversity is already very limited in the Holstein population. The effective population size is down to 50,” he explained. “If you were a conservation geneticist, you would consider that population in danger in a genetic sense. We need to conserve our female variation as best as we can.”

Inbreeding depression may be responsible for some of the reduction in fitness traits, and begets the questions:

Why do we need reproductive programs such as double ovsynch to get cows pregnant?

How are the people who buy our products going to feel if they knew it took all those injections to get cows pregnant?

“We do need to pay attention to inbreeding, and we do need to look for ways around it,” said Cole.

“Stacking pedigrees more intensely is a problem, and if it continues, will come to resemble pig and chicken breeding,” said Cole. “This is not necessarily bad, but do we want our dairy enterprises run like a chicken or swine operation?

“There is no simple solution to inbreeding,” said Cole. “It’s going to take a commitment on everyone’s part. A.I. companies need to identify outcross pedigrees. Breeders need to purchase semen from some of those bulls so there is incentive to produce those animals. Are we willing to give up a few points of Total Performance Index (TPI) or NM$ for the broader, long-term good of the population?”

“There is no easy magic trick here — we got ourselves into this, and it’s not going to go away tomorrow,” Cole went on to say.