It’s been 10 years since genomic testing was introduced to the dairy industry. This valuable tool has provided breeders across the globe the opportunity for much faster genetic improvement in their dairy herds. To fully assess the impact of genomics, Michael Lohuis, vice president of research and innovation with Semex, kicked off the 2019 National Genetics Conference held in conjunction with the National Holstein Convention in Appleton, Wis., in June.

In making his assessment, Lohuis drew upon 19 years of experience with Monsanto and four years as a professor at the University of Guelph. To bring the discussion to life, Lohuis created a full-scale report card on how the genomic tool has performed to date. Lohuis started off with the subject of “Genomic Evaluation.”

Voted with money

When we look at the usage rates of genomic bulls, breeders have voted with their pocketbooks. While proven bull breedings have diminished over time, they still play a role. However, the majority of semen sold today is from young genomic bulls. In 2017, young genotyped bulls represented 69 percent of breedings.

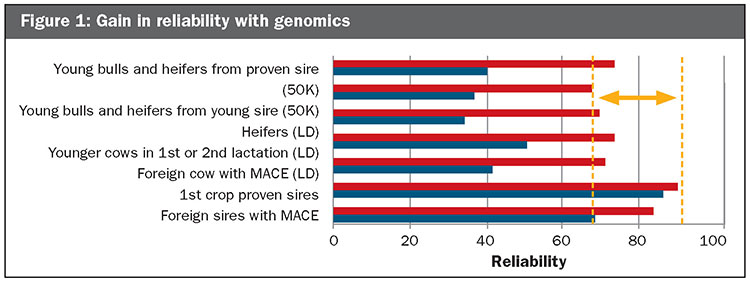

The improved reliability as a result of genomics versus traditional methods is seen most in young bulls and heifers from proven sires (73 percent reliability versus 40 percent), young bulls and heifers from young sires (67 percent reliability versus 36 percent), and heifers (69 percent reliability versus 34 percent). These values are also shown in Figure 1.

When it comes to first-crop, young sires, there is less to be gained from genomic information, as the progeny test data from milking daughters is already informative. The tests also have been valuable in improving the reliability of foreign sires and cows as they continue breeding up the chain, regardless of which country they reside in. That’s because modern-day dairy breeds share germplasm globally through international semen sales.

There is a reliability gap between proven sires and genomic young bulls — even with genomic testing. Proven bulls still have the advantage and tend to be priced reasonably, but if you want to be right on the forefront, then really, the genomic sires are the ones delivering.

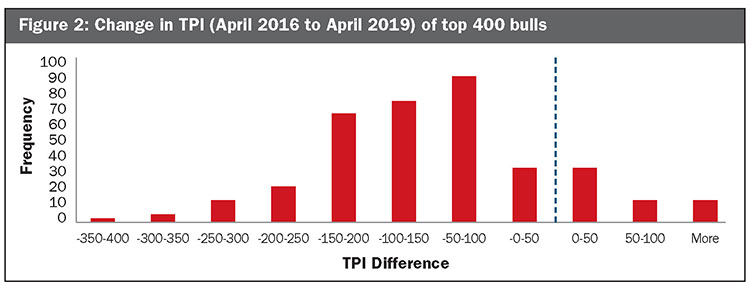

“If you look at how genomic sires compare, when you look at the top Total Performance Index (TPI) bulls from 2016 and their change in TPI through 2019, on average they dropped 150 points — some more, some less,” said Lohuis.

“When you’re studying genetics and genomics in school, one of the questions that will come up is ‘If you take a top sire and use it across a population, will you expect them to go up more or go down more?’ The answer, in theory, is they should go up as often as they go down, so clearly, we have some bias going on,” said Lohuis, who thinks we can do a better job correcting the slippage found in genetic predictions.

“As long as they rank the same and we know there is bias, there’s really no harm done,” theorized Lohuis. “The reasons the data changes over time is you’re adding information on different combinations of SNPs, where they might not be well represented in the beginning, have actually added information on some of those underrepresented SNPs.”

On top of that, Lohuis commends the industry on preselecting bulls. “The A.I. industry does a good job of eliminating young bulls that don’t have the potential to make it to the very top. That preselection bias is part of what’s coming into play as our genomic evaluation systems are expecting them to not be preselected,” said Lohuis. “And, when we add preselection bias, we start to get instability in top animals. We can move toward a single-step evaluation that will hopefully improve and remove some of the bias.

“When you’re a breeder or A.I. stud, you market on the numbers, the rank,” said the lifelong geneticist. “When we look at the same 400 bulls and compare their TPI ranking from April 2016 versus April 2019, the plot is scattered. Their correlation of 0.36 is lower than expected,” he went on to say. “This means that in that plot, there was re-ranking going on. Much of this is due to changes in the TPI formula over time, since correlation is higher for individual traits. Nevertheless, the plot tells us that the re-ranking in the very top part of the population occurs more than it should.

“The reason behind this is heritability at the top of the population is not going to be the same as the main population,” said the Canadian. “We’ve reduced the amount of genetic variation, so re-ranking, especially if you’re marketing bulls, cows, or embryos, is a bit of a concern,” he said. “With that being said, can we do something to create a system that focuses on the top part of the population and improves the correlation?”

Lohuis’ final grade for the genetic evaluation was an A minus. “The application of the genomic theory happened relatively quickly, with a very quick uptake of new technology,” he said. “There is, perhaps, too much re-ranking of top animals,” he added in explanation of not assigning an even higher grade.

Much younger parents

“Genetic Improvement” was next on the report card. The big change in this category has been generation interval, as average parent age has gone down significantly. “Even in 2010, the average age of a bull dam was right at 4 years of age, and now bull dams are just over 2 years of age,” said Lohuis. “Even more drastic of a change has been the bull sires, which went from age 7.5 years in 2010 to just over 2 years in 2018.

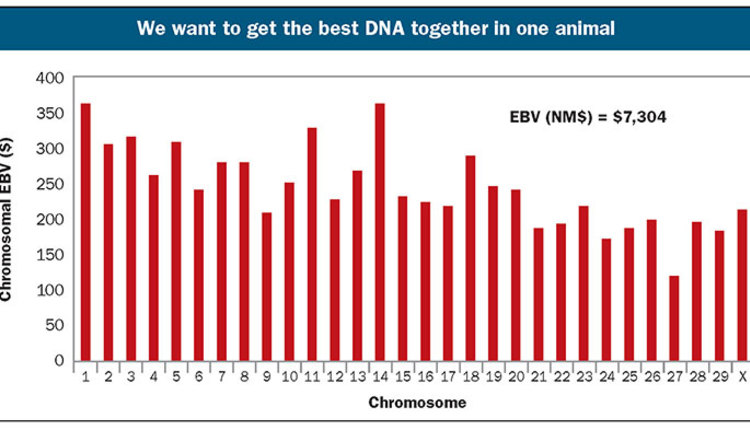

“The genetic gain is perhaps the most impressive statistic, with an additional average Net Merit (NM$) gain calculated at $50 per cow per year with genomics,” said Lohuis. “The additional gain for the population as a whole tops $4.5 billion over 10 years, with an actual return on investment ratio of 45:1,” he continued. “No other species has reported that kind of return, and breeders have tripled their rate of response with a great return on their investment,” he said, driving the point home.

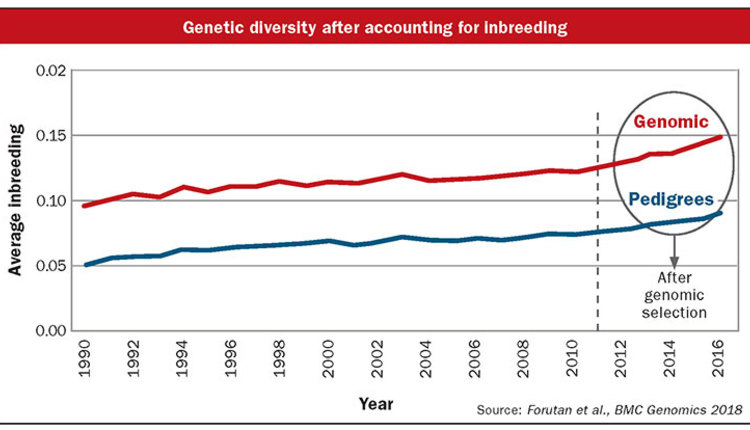

“When looking at other major traits that were low heritability, including fertility, udder health, and longevity, we knew these were all very important, but we couldn’t put very much pressure on them because the heritability was so low,” he said of the pregenomic era. “The advantage of genomics is if there is a large enough reference population, and we invest in that by collecting phenotypes, we can actually improve confidence,” he said. “We essentially tripled the rate of response for these low heritability traits, and as a result, we are now seeing positive trends in our population.”

Lohuis awarded genetic improvement with an A plus . . . the highest grade in the six categories. “We’ve doubled or tripled our genetic progress, with the most significant progress on low-heritability traits. Our improvement has also provided a great return on investment for producers,” he said.