The author is the principal in ANDHIL LLC, a St. Louis-based consulting firm.

Dairy heifers have fluctuated in price over recent years, while young stock numbers have been near record highs relative to lactating cows. With the advent of sexed semen, it seems many dairy farms have embraced the technology and often raised most of the resulting heifer calves. If expansion of the dairy farm did not ensue, and all bred heifers were calved, farms might find themselves in a position where lactating cows were pushed out of the milking herd.

Perhaps this scenario is what caused some overarching management changes in the industry. One common example has been the use of genomic testing on young heifer calves to determine which would be kept, grown, bred, and calved into the milking herd.

Now, more herds seem to be using another strategy. By breeding the lower third of the lactating herd to beef breeds, this reduces dairy semen usage and the total number of heifer calves born into a herd. Of course, we all remember 2019 when bred and close-up heifer prices nosedived to around $1,250 to $1,500, depending on regional and local markets.

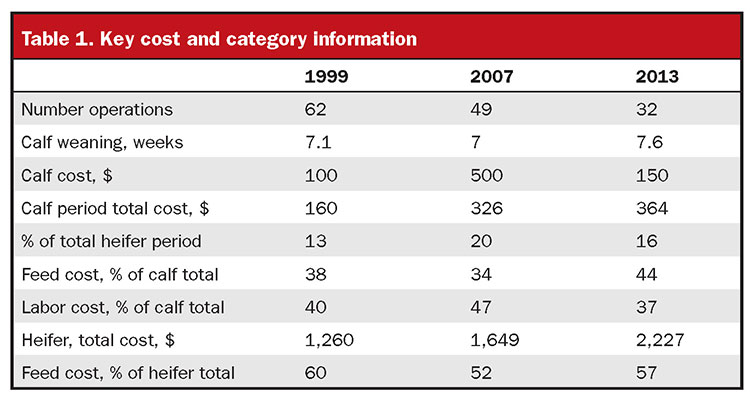

The University of Wisconsin-Division of Extension has done three comprehensive statewide studies in 1999, 2007, and 2013 in this subject area. Graphs and more elaboration on these studies can be found in Chapter 9 of my book “Dairy Calf and Heifer Feeding and Management — Some Key Concepts and Practices.” Key costs and parameters varied considerably in each year studied as captured in the table.

Age at weaning went up in 2013 when compared to 1999 and 2007 levels. Meanwhile, the cost of a calf skyrocketed from 1999 to 2007, but then dropped by 70% by 2013. Calf period total costs doubled from 1999 to 2007, but then only went up by 12% from 2007 to 2013.

The total calf period costs as a percentage of total heifer raising costs, which included calf period costs, was relatively low at 13% in 1999, went up to 20% in 2007, but then declined to 16% in 2013.

Feed cost as a percentage of total calf period costs was similar in 1999 and 2007 at 34% and 38%, but rose to 44% in 2013 even though calf operations largely converted to the cheaper option of pasteurized waste milk from milk replacer, according to the reports. Adversely, starter costs were much greater in 2013 than in 1999 and 2007, reflecting the much greater feed costs in general at that time.

This occurred even though labor costs per hour inflated from $7 to $12 to $13 between 1999 and 2013. Management costs rose from $12 to $20 to $23 per hour during the same time periods.

For total heifer costs, the largest segment was feed costs, capturing 60%, 52%, and 57% of the total cost, respectively, for 1999, 2007, and 2013. In 2007, total costs per day during the calf period were about $5.50, or twice what it was in 1999. But feed costs as a proportion of total calf costs dropped from 38% in 1999 to 24% in 2007 because labor costs rose proportionally more from 40% to 47%. In general, 2007 feed costs were lower than 1999 throughout the heifer body weight categories and never became greater than the calf period cost as had occurred in 1999.

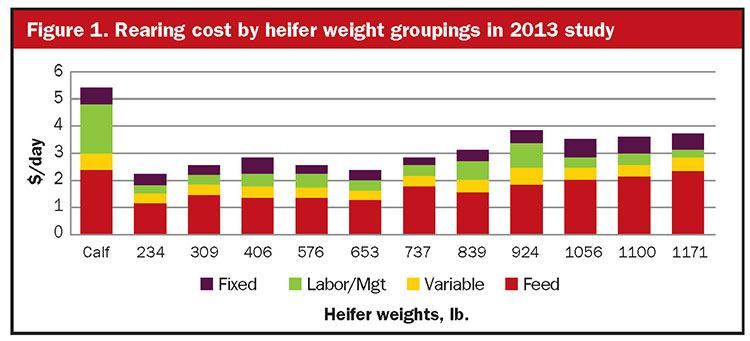

In 2013 (Figure 1), total calf costs per day were similar to 2007, but feed cost was greater despite operations largely having converted to feeding primarily pasteurized waste milk. In general, feed costs were considerably greater across all heifer categories in 2013 versus 2007.

In fact, for 2007, heifer feed costs were less than $1 daily for the first six heifer categories, and reached a peak at $1.58 per day for the 1,209-pound heifer category. By contrast, in 2013, all heifer categories were in excess of $1 daily feed cost with the last three categories exceeding $2 daily feed costs. This resulted in feed costs as a percentage of total costs rising from 52% to 57% for 2013 versus 2007, although it was even greater in 1999 at 60%.

What it means

Now let’s do some simple arithmetic analysis. I think too often dairy producers focus on the calf period as a place to cut costs. This philosophy grew out of the view that calves are strictly a cost period and not likely to affect how much milk they produce when they become cows.

That is only true on a daily per-head basis, but most definitely not true when evaluating total costs to raise a heifer. Using a 60-day calf period from the figure at about $5 per day equals a total cost of about $300. For the rest of the 22-month heifer growing period and using $3 per day at 660 days, it equals about $2,000. Add the $300 calf period for a total of $2,300, of which only about 13% is for the calf period.

Let’s say a dairy producer cuts back to “save” $50 on calf costs. That is a pittance (2%) of the total costs to raise a heifer. I would argue that is the worst time to try to save money as the calf is the most efficient animal on a dairy at converting nutrients to growth. Further, it’s the most sensitive animal on a dairy to change and challenge. Yet, that period has the most impact on what kind of cow they become, including their level of milk production.

An extensive Cornell University research herd study with 10 years of calf growth data and subsequent first lactation records (1,244) found that for every additional pound of average daily gain (ADG) (within the range of 0.29 to 2.7 pounds per day) by weaning, heifers produced 850 pounds more milk during their first lactation and 2,280 pounds for their combined first three lactations.

Another New York herd had 623 first lactation records over a five-year period and had an even 30% greater response than the Cornell herd. A subsequent meta-analysis of 12 published studies plus this Cornell study indicated that for every pound of preweaning daily gain difference, first-lactation milk yield rose by 1,550 pounds.