The author is the director of nutritional research and innovation with Rock River Lab Inc., Watertown, Wis., and adjunct assistant professor, dairy science department, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

This year will go down in the annals of history as one for the ages. Indeed, 2020 had both immense challenges and immense opportunities . . . both are coming to light. As for the crop year, corn for silage followed suit.

As the growing season progressed, I was projecting moderate to poor corn silage forage quality for many dairy forage growers throughout the Midwest. We’ve understood the crop fiber quality to be influenced by heat and moisture available relatively early in the growing season, prior to tasseling. At an earlier point in the year, many Midwestern growers were flush with moisture and heat units when corn was V5 through V7 stage . . . that’s when forage fiber quality is thought to be determined. Due to the heat and moisture, I expected the growing environment to equate to rougher fiber quality. However, this negative interaction between environment and genetics did not materialize as expected.

Not just a Midwest issue

The Midwest wasn’t alone in this development, either. The Western region of the country experienced unprecedented conditions to finish the season, while the Eastern region seems to be a wild card in quality. The following highlights some interesting silage quality observations for the 2020 crop.

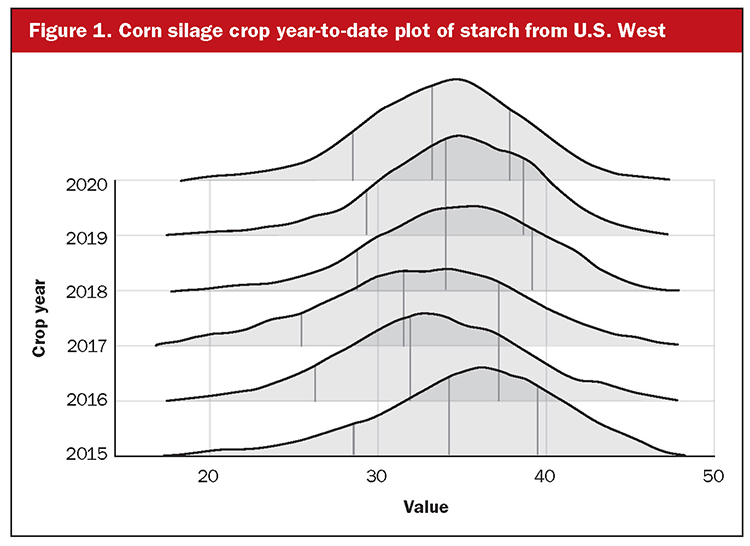

The Western region experienced drier-than-normal growing conditions. This is not a new phenomena, as the West typically relies on irrigation to bring the corn crop to silage maturity regardless of what little rainfall comes during the spring and summer. Though this year, however, wildfires in the region may have had an impact on grain yield in silage corn.

Corn needs adequate light to reach the finish line, along with heat and moisture. This year, the wildfire smoke may have shaded out the crop. Numerous industry colleagues have confirmed and commented the crop was delayed for a week or two in reaching maturity relative to prior years. This altered growth pattern is showing up in samples for Western silages.

Figure 1 details Western silage sample results for starch content for 2020 and earlier crop years. The starch content appears to be substantially lower in 2020 than in both the 2019 or 2018 crop years. Despite fiber digestibility and other nutrition parameters appearing similar, I’m anticipating slightly less energy content per pound this year due to lower grain and starch content.

Surpassed expectations

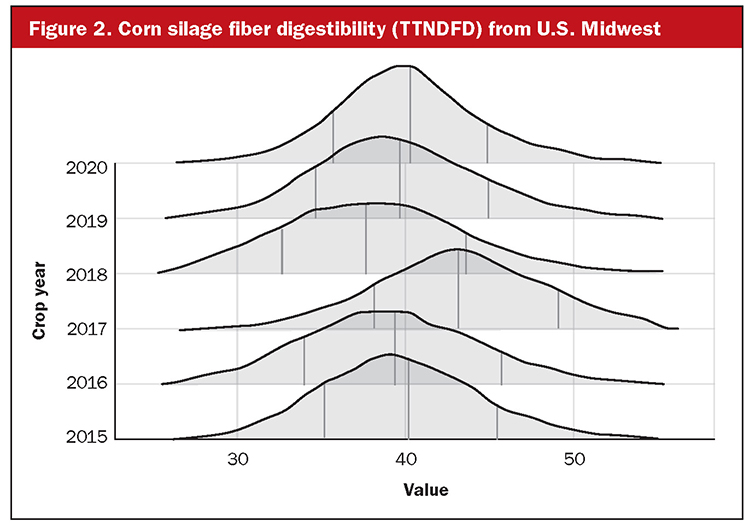

As discussed earlier, we often expect that fiber digestibility will trend lower when the growing crop has sufficient heat units and moisture early in the year. Many Midwestern growers had more than adequate heat and moisture earlier this year; however, the crop prognosis did not materialize as I was forecasting in July. I’m happy to admit where I’m wrong, especially when it’s to the dairy industry’s benefit.

This year’s silage quality looks to be above average, and I’m questioning my prior “genetics by environment” understanding. The silage crop is testing to be similar in fiber and starch levels to last year but lower in lignified fiber content and greater in fiber digestibility.

The total tract NDF digestibility (TTNDFD) estimates for this year’s silage can be visualized via the year over year in Figure 2. The TTNDFD accounts for undigestible fiber and digestion rate, hence it is a simple value to interpret but also powerful, in that four different fiber digestion measures are integrated into one. Recent field survey experience in the Midwest suggests that a unit increase in silage TTNDFD could be associated with up to a 0.75 pound gain in energy-corrected milk.

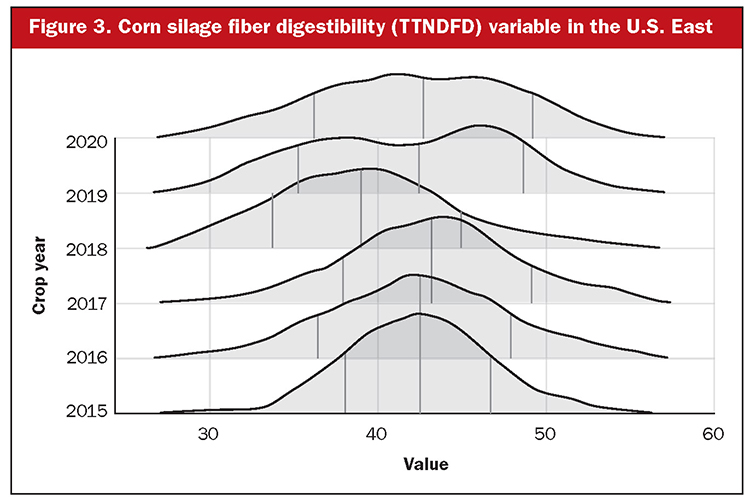

Eastern silage is a wild card

Pockets of Eastern dairy forage growers experienced drought, while others had ample or timely rains. Fiber and starch content appear similar relative to prior crop years, but the fiber digestibility looks to be wide ranging. While the Midwest is demonstrating a typical bell curve, indicating a normal distribution, Eastern U.S. silage sample fiber digestibility distribution looks like my kids play dough after they run over it repeatedly and flatten it out with their toy tractors.

This flattened distribution is evident in Figure 3. The trend mimics what we observed for 2019, where silage seemed to fit in either a high-quality or lower-quality category. If you farm in the East, ask your nutritionist about your fiber digestibility relative to others in your area. If the TTNDFD measure is not reported, ask your nutritionist about benchmarking with both undigested fiber content and potentially digestible fiber digestion rate. Overall, benchmarking in the East this year will be more difficult due to apparent growing season differences within the region.

Each year we continue to learn. As the seasons come and go, we come away with new questions. This year is proving no different. The interaction between the growing and environment and crop quality proves intriguing, but we have much yet to learn after this year’s experience. I encourage farmers, nutritionists, agronomists, seed companies, and researchers to continue work in this area. Replicated plots will help us toward a better genetics by environment (GxE) understanding.

If your team aims to plant plots, consider monitoring several of the same hybrids, in consecutive years, along with soil fertility measures. The benefits to better understanding the seed genetics interaction with the growing environment will prove incredibly valuable.