The authors are a student at State University of New York College of Agriculture and Technology at Cobleskill and a senior extension veterinarian at Cornell University.

It's Monday morning and you start the day by feeding calves as the sun comes up over the hills. Most of the calves are eager to get their pail of milk, but there are a couple of scour cases in the preweaned calves. There is one particularly poor calf that has been especially unthrifty for the past few days. You’ve been treating it with electrolyte therapy and switched to bottle feeding, but the calf seems to be going downhill fast. Overall, you are frustrated, as the on-farm pasteurizer is supposed to keep your calves from scouring, yet here you have a calf so close to dying from scours and dehydration.

What is pasteurization?

Pasteurization was first developed by Louis Pasteur who proved that microbes responsible for food spoilage could be avoided through elevating temperature to 63°C (145°F) for 30 minutes or 72°C (162°F) for 15 seconds. This heating process improved food safety and lengthened the shelf life of food with no changes in product quality and only minimal changes to vitamin content.

Under ideal conditions, pasteurization reduces the bacteria population by log5, or 99.999%. In other words, if one started with 100,000 bacteria, pasteurization would reduce this population to just 1 bacterium. As a result, pasteurization rapidly became common practice, and even law, in the food systems of many countries.

From waste to quality feed

Pasteurization has gained traction in the dairy production setting with on-farm pasteurizers to reduce bacteria levels in waste whole milk fed to calves. On most dairies, there is nonsaleable milk or waste milk in the form of transition milk, mastitis milk, and antibiotic-containing milk. Use of this milk as a source of liquid feed for calves is a cost effective way for farms to utilize otherwise unsaleable milk.

However, depending on the animals from which the milk was produced, cleanliness of how the milk was harvested, and time and conditions under which it was stored, raw waste milk may have very high bacterial populations. Studies show that raw waste milk fed to calves has highly variable bacteria counts of up to a billion bacterial colonies per milliliter (mL).

High bacterial populations have been linked to diarrhea and poor weight gains in calves. With proper pasteurization and handling of liquid feed, calf exposure to high bacterial populations is greatly reduced, resulting in lower rates of illness and death with improved weight gains.

Before placing blame on the pasteurizer for not operating properly, it is important to review the entire processing procedure from collection of raw waste milk to delivery of the pasteurized milk to the calves. Curdled, poor quality milk placed into a pasteurizer vat will not be improved during the pasteurization process. By collecting milk samples throughout the process and inspecting equipment associated with the pasteurizer, it is possible to identify the critical control points.

Samples should include:

1. Raw waste milk from the vat prior to pasteurization.

2. Post pasteurization milk.

3. Milk being dispensed from the nozzle at the beginning of the feeding.

4. Milk being dispensed from the nozzle at the end of feeding.

These samples will help to determine if the pasteurizer is operating properly and if quality pasteurized milk is being delivered to calves, or if it is being contaminated in the process. A milk laboratory that performs quantified cultures will break down the types and number of bacteria present in each sample to determine if a problem exists in the process.

The example in Table 1 indicates that the pasteurizer is performing well in reducing bacteria levels from the prepasteurized sample to the postpasteurized sample. However, a problem exists in the delivery of milk to the calves. Total bacteria levels rose from 1,200 colony forming units per milliliter (cfu/mL) in the postpasteurized sample to 27,000 cfu/mL in the first delivery sample and then to 50,400 cfu/mL with the last delivered sample.

Time to dig deeper

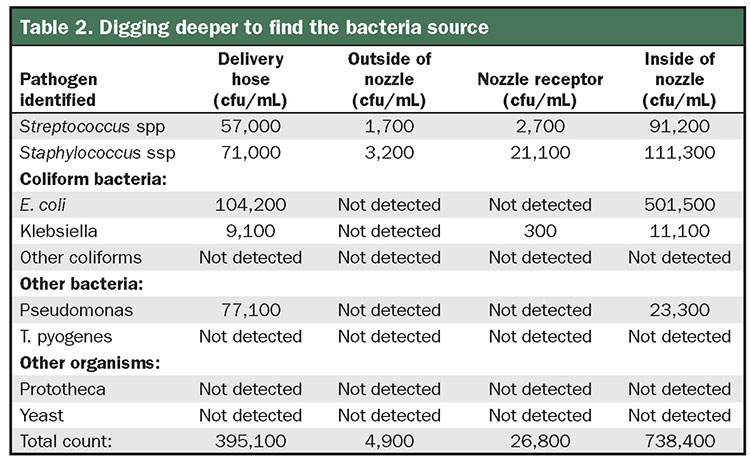

Quantified cultures indicated that the pasteurizer was operating properly. Attention must now focus on how the pasteurized milk delivery. The following samples were collected during the process of feeding calves:

1. Swab inside the delivery hose.

2. Swab of the outside of the nozzle at the end of the hose.

3. Swab of the rubber receptor where the nozzle is held.

4. Swab of the inside of the nozzle when taken apart.

The primary sources of lingering bacteria were the dispensing apparatus, the hose, and the nozzle, as shown in Table 2. These parts of the pasteurizer system often show evidence of bacterial buildup over time without routine inspection and manual cleaning. After replacing these parts, the bacteria count of delivery samples dramatically fell.

On this particular farm, pre- and postpasteurization samples along with delivery samples are now cultured on a monthly basis to monitor bacteria levels and the effectiveness of the pasteurizer and feeding process. The cases of scours in the calves have dropped as issues arising from the pasteurization and feeding process are quickly identified. We are now more proactive about keeping the preweaned calves healthier.

Thoughts on maintenance

While precise procedures and schedules may vary between farms, pasteurization methods, and equipment dealers, there are several standards that should always be met:

1. Your pasteurizer must be thoroughly rinsed and cleaned after every use. Always follow your manufacturer’s guidelines and chemical instructions, but, in general, the machine should always be rinsed of any milk residue, scrubbed with soap and hot water, and then allowed to course through its factory-set cleaning cycle.

An alkaline rinse may also be recommended in order to raise the range of pH during cleaning, as this kills bacteria even more effectively. Any gaskets or removable parts (such as a nozzle) should be scrubbed by hand.

An acid sanitizer should be flushed through the entire system. After the cleaning cycle is complete, another thorough rinse should be done with hot potable water. Lastly, the vessel should be closed in order to prevent debris, flies, or other contaminants from entering the pasteurizer and interfering with the milk.

2. Proper water, heat, and electrical sources must be sufficiently available to the pasteurizer. Check your equipment manual for the specifics to ensure that the correct heating, cooling, and holding temperatures are being achieved.

3. Milk should be relatively fresh. Pasteurization will not improve low-quality or spoiled milk.

4. Keep accurate records and monitor what you are feeding your calves. Consider routine analysis of liquid feed samples for nutritional and microbiological quality. Monthly schedules should be established for farm pasteurizers with rigorous weekly schedules for start-up programs.

5. Routinely check the accuracy of your pasteurizer’s temperatures with a digital thermometer — is it really getting up to the temperature that it claims to be?

6. Remember that your pasteurization equipment is just that — equipment. Just like your milking system or heavy machinery in the field, equipment breaks and wears down and must be properly maintained.

While pasteurization is a revolutionary tool in the food industry and has the potential to eliminate most harmful bacteria from liquid calf feed, the responsibility falls on you to be aware of the state of your pasteurizer and the quality and safety of its products. Remember to always investigate issues thoroughly and critically to ensure the best care for your preweaned calves.