In my last article, I described how to identify cows that aborted in the dairy herd as a step to improve the reproductive performance. After determining that a herd has a high abortion rate, a deeper analysis is needed to avoid expensive and futile actions. Here are some ideas to tackle this issue.

One question to answer is whether the abortions are being caused by infectious agents, such as bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) virus, Brucella abortus, or Neospora caninum, to mention a few. To address this concern, a manager can scout the records and determine whether the abortions are actual or apparent. An actual abortion implies that an aborted fetus has been found, whereas an apparent abortion has (supposedly) occurred because a cow is rebred or diagnosed open after it has been diagnosed pregnant.

Using the tool I described in my previous article, I screened all the abortions of a herd with a 22% abortion rate and concluded that none of them were actual abortions. This finding suggests that infectious agents leading to late abortions are unlikely to be a problem in this herd, and the apparent abortions are mostly early embryonic losses.

Although unlikely, an erroneous pregnancy diagnosis is another possible explanation for a high abortion rate. Considering the definition of apparent abortion, a cow wrongly diagnosed pregnant when she is open will result in an (inexistent) abortion that can lead to inaccurate assessments in the herd. Addressing this possibility may be extremely difficult in most herds. However, it is possible in herds measuring activity.

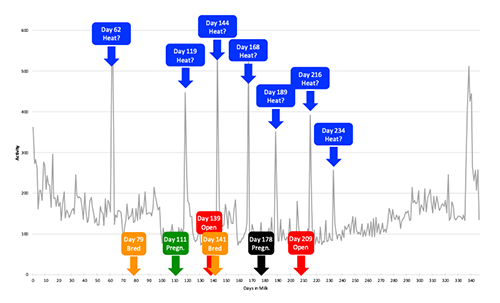

The figure above, for example, depicts the activity and the reproductive records of a specific cow that has aborted twice. In this herd, the voluntary waiting period is 78 days, and cows are bred following synchronization protocol. On Day 111 after calving, this cow was diagnosed pregnant from a breeding on Day 79 (green arrow). However, after showing high activity on Day 119, this cow was palpated again and diagnosed open on Day 139. In this case, the lack of activity after breeding supported the idea that early embryonic loss may have occurred.

Now, let’s see what happened later in lactation. On Day 141 after calving, this cow was bred for a second time, although her activity never stopped after breeding. Even more, her high activity was seen repeatedly at 18 to 27 days, indicating possible estrous postbreeding. Still, the cow was diagnosed pregnant on Day 178 (black arrow) and open again on Day 209 (red arrow). The latter indicates a second apparent abortion for this cow. However, was this second abortion real based on the post breeding activity? Maybe not, and we will never know.

The moral of this article is that a lot can and should be learned after seeing a key performance indicator, such as the abortion rate of the herd. Given that an erroneous diagnosis may lead managers to expensive and futile actions, spending time analyzing data is worth the effort. Nowadays, combining records with activity data makes this analysis easier and faster.