The author is an assistant professor of applied economics at the University of Minnesota.

To answer when-type questions, professional market analysts pore over hundreds of data sources and gather soft intelligence through scores of phone calls and emails with industry contacts.

There is another type of inquiry that is equally critical for the dairy farm’s long-term survival: the “what” questions.

What are the events, structural changes, policy developments, and other influencing factors that are likely to happen? What will be the impact on the dairy sector? What about the timing of those events?

The timing answer may be the most elusive of all. That being noted, this Milk Check Outlook will take a long horizon approach.

Two game changers

DMC is designed to bring about stability to farm finances for producers with a few hundred cows. Growth management programs seek to coordinate milk supply with demand. My concern is that, when combined, these programs may have unintended consequences, which may be irreversible.

Different one decade ago

Just 10 years ago, the social contract in the U.S. dairy sector was that any given dairy farm member of a cooperative could grow as they wish, and the cooperative’s primary mission was to find a home for that milk. Today, the social norm is that the main benefit of cooperative membership is that a producer need not fear they will lose existing market access. Ability to grow is now a privilege, no longer a guaranteed right.

Producers directly contracting with a privately owned processor face a similar fate, with even less guarantees regarding long-term market access. This change has allowed cooperatives to be more deliberate with directing their financial resources rather than having to prioritize capacity for converting raw milk into bulk commodities with low added value.

Two groups of farmers

However, at the same time, this change has further concentrated growth in U.S. milk production in just a few milk sheds. This trend, if continued, threatens to create two classes of dairy producers: those with know-how and financial resources to build the next facility at a distant location, and others locked into their current location.

When a major national processor wants to build a brand new plant, they no longer ask where is the abundance of milk, but where can milk supply most easily and economically be swiftly expanded. Producers who can choose where to milk also get to choose how much to grow. Others, locked in their location, face constraints. Policy instruments that can address this problem do exist and are in use elsewhere.

In Australia, a recently passed dairy regulation offers dairy processors a choice: If they require the farmer to ship milk exclusively to them, they cannot impose volume limits or two-tiered pricing. Alternatively, if a processor wishes to impose volume limits or base/over-base pricing, they must allow producers to also sell milk to another buyer.

In a parallel lane, Dairy Margin Coverage has dramatically improved the financial situation on smaller dairy farms. The Agricultural Act of 2018 has increased the available coverage from $8 per hundredweight (cwt.) to $9.50 per cwt., reduced the Tier 1 premium, and replaced average with Supreme alfalfa hay in the feed cost formula. These changes have made the program extraordinarily beneficial to smaller dairies.

A bigger cost forecast

For 2021, forecasted payment is $2.54 per cwt. Had DMC been in existence since 2006, the average benefit, net of premiums, over the past 15 years would have been as high as $1.63 per cwt. Under DMC, Tier 1 premiums covering the first 5 million pounds were set as low as was deemed necessary to convince even the most skeptical dairymen that this is a generous income safety net.

In contrast, Tier 2 premiums are set as high as needed to make sure that few would want to use it. DMC has succeeded in reducing the dairy herd dispersals. In 2021, the dairy farm exit rate in Wisconsin was 5.4%, down from 11.2% in 2019. However, my concern is that a side effect will be reduced incentive to pursue efficiency gains through growth due to an abrupt and steep risk wedge once the herd grows beyond 250 cows.

What does the future hold?

Farm bills authorize dairy programs for five years. In deciding whether to come back to the family farm, young adults from dairy families must contemplate what is likely to happen over the next 40 years. That is eight farm bills.

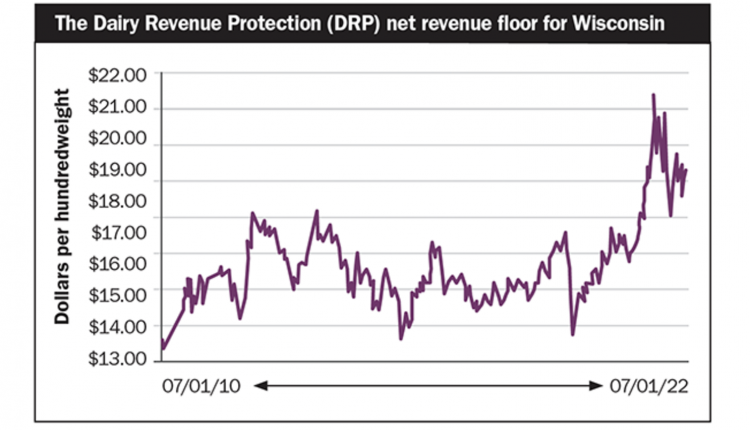

More in the next generation will want to continue the family legacy if they believe that their family farm has a chance, and the will, to remain competitive over their lifetime than if they see that their farm’s business plan is centered around a safety net that may be dissolved in a few years. This problem can be resolved through a more dynamic subsidy structure, applied either to DMC or programs administered through the USDA Risk Management Agency. The current programs include Dairy Revenue Protection and Livestock Gross Margin–Dairy.

The number of dairy farms in the U.S. has been shrinking for at least three generations. However, unless policy instruments are implemented to enhance competition for farm milk and provide the dairy farmer with freedom to pursue innovation and growth, in 15 years we may look back on 2021 and find a hyper-consolidated dairy sector. Policy choices exist today to alter this potential outcome.