In a typical year, high-moisture corn and corn silage would be feeding to nearly its full potential by this time in the calendar year.

This year is different.

What’s more, by this time of the year, we tend to have had several months experience and a rock solid understanding of any antinutritional factors associated with the crop, like yeast or mycotoxin contamination.

This year is different.

The 2021 corn crop for silage and grain now looks to be dragging on many farms well into 2022 in newfound ways — both nutritional and antinutritional. We’ve extensively discussed grain and starch digestibility. We’ll do so again here as starch digestibility still lags.

Back around the holidays, I also wrote about crop cleanliness with the Hoard’s Dairyman Intel article “What did Santa deliver in our corn silage?” portraying that crop cleanliness was not a major issue for the 2021 crop. However, despite seemingly solid data in hand back in December, my 2021 crop mycotoxin views have shifted as better information comes into clearer view.

Nutritional sandbags with the 2021 silage

Each year’s new crop slump is attributed to fresher silage and less-than-ideal rumen grain and starch digestibility. Thanks to extensive research in this area, we understand the impact factors are kernel processing or grind size, seed genetics, growing season, and the extent of fermentation. This latter factor is the reason that corn silage and fermented high moisture corn takes several months to feed to its full potential.

This year, Mother Nature yielded corn silage and grain with much harder grain for the eastern half of the U.S. This equates to suboptimal starch digestibility, which continues to come up in discussion with dairy owners and nutritionists from South Dakota through to New York. Milk components are way up, and this is, in many cases, attributable to less digestible grain.

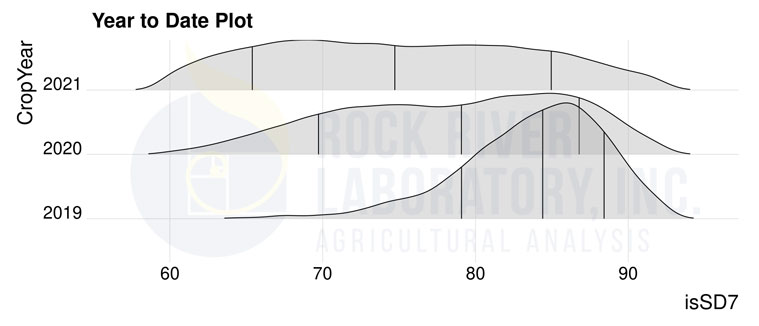

For a visual here, see Figure 1. We’re clearly down 5% to 20% in starch digestibility year over year at this point. In my opinion, silage won’t feed to its full potential until April or later. This is months behind, as the goal here is 85% to 95% starch digestibility. Ensure your nutrition program accounts for this fact.

Mycotoxins poking more holes in 2021 silage quality

In December, we should have been in a relatively good position to understand the corn silage and grain crops’ antinutritional value. The crop was harvested on time from August through October, so we had a fair amount of data to review.

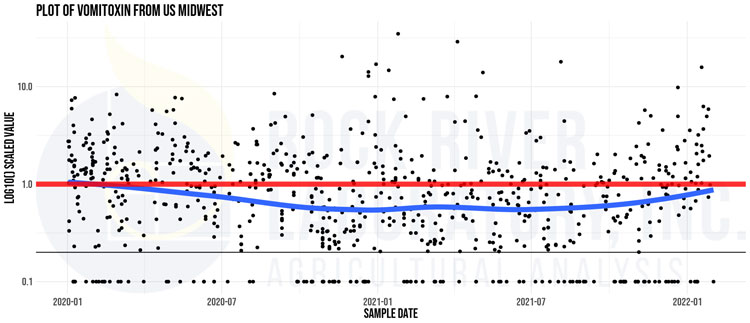

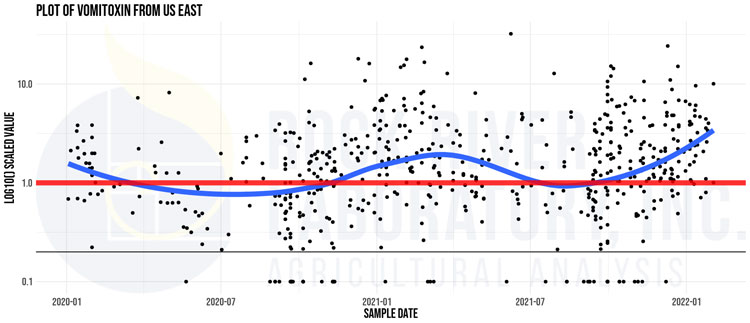

Around the holidays, I commented that the eastern U.S. looked to have some nutritional challenges, yet the Midwest crop appeared relatively consistent in mycotoxin load relative to prior years and didn’t appear to be a major concern. This has changed slightly as the Deoxynivalenol (DON), or Vomitoxin, levels now look to be on an upward trend for both the eastern and midwestern U.S. Figures 2 and 3 detail DON levels with corn silage samples analyzed for Midwestern and Eastern silages, respectively.

This new trend may be due to two different factors:

- Additional samples and data coming online through the laboratory that better detail the 2021 crop

- DON level increasing during ensiling. University of Wisconsin plant pathologist Damon Smith has recently published data detailing this second point. This potential increase in DON level during ensiling warrants further discussion among industry experts and your nutrition team.

Rounding out with a positive note, thankfully spoilage yeast levels and other mycotoxin levels in silage and grain continue to look to be relatively mild for 2021 silage. Fiber digestibility also appears to be up for the Midwest but will be highly variable according to region.

To close out and cite recent discussions with a colleague when he asked what the industry trends look to be as of late, I responded with one word — volatility. At that time, I was speaking to futures prices and commodities; however, volatility also appears to be existent with our 2021 corn crop. Don’t assume consistency with this year’s silage and grain. Work closely with your nutritionist to have a plan in place to work with this crop as we continue feeding into it.