U.S. milk production came in right at forecast for February, down 1% from last year. We’re often asked to interpret these reports as bullish or bearish, and this one is a tough call.

Milk production has been coming in lower than forecast around the world for the past four months, so production being at forecast feels bearish, but being down 1% isn’t really bearish news.

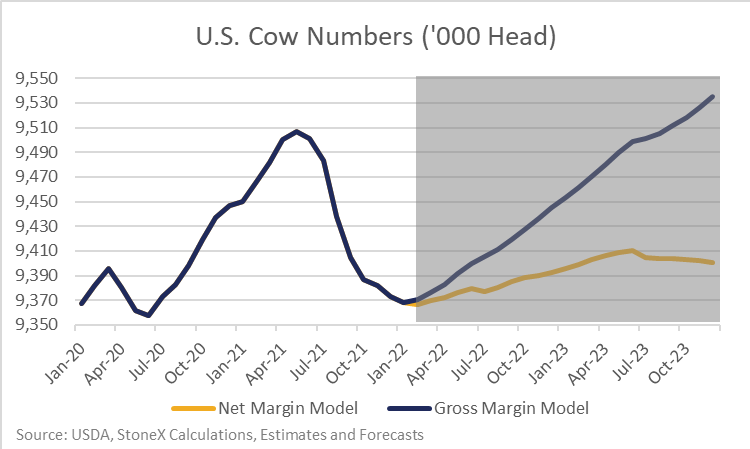

I would call the report neutral to slightly supportive with one caveat: the size of the dairy herd climbed by 3,000 head between January and February . . . this was the first gain in the herd in eight months. The upward movement in cow numbers was expected given how high milk prices reached in late 2021. However, a follow up question must be asked, “What should we expect for herd and milk production growth moving forward?”

For the past 15 years, my milk production forecasting models have been built around feed costs and the price of milk. The other costs of production fluctuate less than feed, and it is harder to track those additional costs on a monthly basis. But energy, labor, and nearly every other input cost has gone up significantly in the past 18 months. That being said, just looking at feed costs understates the pressure dairy farmers are feeling.

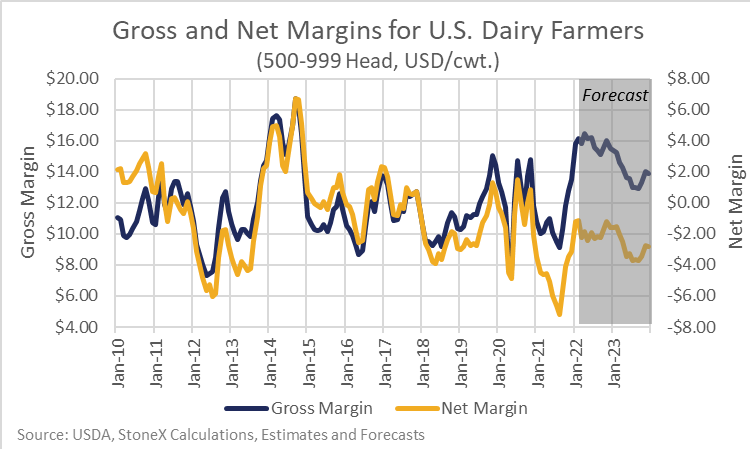

The graph “Gross and net margins for U.S. dairy farmers” shows our calculated gross margin (blue line). This is simply the price of milk minus the cost of feed and the net margin (gold line). It is an attempt to take into account all of the other costs as well.

From a gross margin perspective, farm level profitability looks very good for 2022. Rising milk prices are more than offsetting the higher feed costs. But from a net margin perspective, which takes into account all costs, profitability looks weak despite the very high milk prices.

Not surprisingly, my milk production models that only incorporate feed costs are pointing toward a rapid gain in the size of the herd over the next 22 months. By the end of 2022, the model says the nation’s dairy herd should be up 0.8% from last year and could reach a new record high dating back over 30 years in the fourth quarter of next year. However, the model built on net margin (total costs) shows a much smaller increase in the herd, putting it up just 0.2% by the end of this year and only tacking on another 0.1% next year.

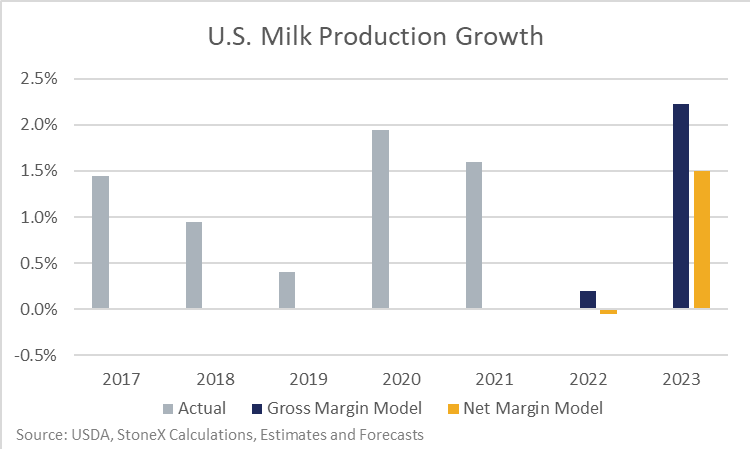

When I look at what the different models suggest for total milk production, there isn’t much difference for 2022. Neither model is forecasting much growth. But the model built only on feed costs is forecasting 2.2% growth for 2023, which would be the strongest growth in 17 years. The less optimistic model that takes into account all costs is forecasting a more modest 1.5% growth.

Assuming feed costs don’t shift significantly higher and milk prices turn out close to forecast, we should be looking at stronger milk production growth in the second half of 2022 and through 2023. The model that takes into account all costs (net margin) will probably turn out to be more accurate than the gross margin model.

We have probably put in a short-term bottom for the dairy herd, which should trend higher from here, although the slope of the climb can be debated. Even with the herd trending up, milk production will likely still be stuck below year ago through June or July, but then we will be looking at significantly better growth during the second half of 2022.