In late September, Foremost Farms sent a letter to their patrons located in the Upper Midwest Federal Order explaining that there would be a 90-cent per hundredweight (cwt.) deduction from their milk checks. The deduction was retroactive to September 1, 2022, with no stated end date.

It’s a large and unfortunate hit to farmer’s milk checks. In the same vein, Foremost Farms does deserve some credit in making the deduction explicit instead of trying to hide its premium structure. Foremost Farms cited rising labor costs, higher costs of raw materials such as energy and packaging to convert milk into finished dairy products, and a disparity between the Class III milk price and the revenue they are receiving from selling cheese priced in its relationship to block cheese price. These are all issues I’ve talked about in articles over the past eight months, and I’m going to make the argument that whether there is an explicit “market adjustment” on your milk check or not, these market pressures are probably showing up as lower premiums.

It’s no surprise that the cost of processing dairy products has grown substantially in recent years. I wrote about Mark Stephenson’s most recent survey of processing costs in February’s article, “Could we see new milk processing formulas?” In addition, the University of Wisconsin economist also authored the article, “Why make allowances matter.”

Stephenson’s survey found that processing costs were up about 28% from the current make allowance levels that are being used in the Class III and Class IV milk prices. If the make allowances were changed to match his survey, it would reduce the Class III milk price by about 83 cents per cwt. and the Class IV by about 95 cents per cwt. There are legitimate concerns about some of the survey results and the industry is trying to hash those out, but processing costs for the average U.S. dairy plant are 75 cents to $1 per cwt. higher than the current make allowances.

Another processing matter

The second big issue that Foremost cites is the block-barrel spread and the negative impact it is having on their returns. I wrote about the block-barrel spread and the possibility of dropping barrels from the Class III calculation in the May article, “Could a cheese price fix improve milk checks?” From 2000 to 2015, CME spot block cheese averaged 3.4 cents higher than the CME spot barrel price, which is close to the 3-cent spread that is assumed in the Federal Order formulas.

The Class III milk price is determined by the average of the block and barrels prices. It doesn’t matter if the cheese plant is producing blocks or barrels — they are (generally) paying the Class III milk price. If the price of barrels moves above the price of blocks (as it has been since April), it raises the average cheese price and, consequently, raises the Class III milk price. If a cheese plant is selling their cheese based on the price of blocks, but the Class III price climbs because of a rising barrel price, the margins for that cheesemaker are going to be squeezed and could turn negative, which seems to be the situation for Foremost (and other cheese plants).

I have heard the argument that milk prices will find the market clearing price no matter what we do with the milk price formulas. We can ignore the higher processing costs and leave the make allowances as-is to try to keep revenue flowing to the farmers instead of the processors. But it’s possible that commercial processors, which are seeing their margins squeezed by higher processing costs, will squeeze the co-ops and the farmers who own those co-ops, when they negotiate the over-order price (premium) they are willing to pay for the milk they buy. We should be able to look at the premium that milk buyers have been paying and see if it has declined as processing costs have increased.

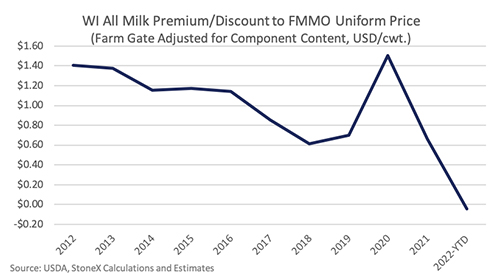

The problem is we don’t have good public data on those over-order premiums (and discounts). The best proxy I could come up with is comparing the USDA reported All-Milk price to the uniform (or blend) milk price in the Federal Orders.

The uniform price in a Federal Order is the theoretical base price that farmers are receiving for their milk. The actual farm gate milk price will have additional premiums that reflect their milk components, quality, volume, and any premium the cooperative is able to charge commercial processors for the milk.

Commercial milk buyers, whether they are buying Class I, II, III, or IV milk, often pay an “over-order” premium that is added to the minimum class price each month. The over-order premium theoretically helps to compensate the cooperative for balancing the seasonal fluctuations in the supply and demand of milk, allowing the commercial buyer to contract for a specific amount of milk each week. The farm gate milk price would also include deductions for milk hauling, checkoffs, and “overbase” and “reblending” adjustments.

The All-Milk price reported by the USDA is derived from a survey of dairy plants. They ask the plants how much milk they bought and how much money they spent for that milk, then divide it out to calculate an average price per hundredweight. It does not include deductions like hauling and marketing checkoffs, but it would include any additional premium, or discount, that the plant was paying for the milk they are buying. The All-Milk price is reported at tested fat content. I’ve adjusted the All-Milk price to a fixed fat and protein content to make it comparable to the uniform milk price.

If we compare the All-Milk price, adjusted for components, to the uniform milk price, it should give us an idea of what additional premium farmers have been receiving from the market compared to just the baseline uniform price. The analysis makes the most sense when you narrow it down geographically.

If we look at Wisconsin, the All-Milk price in 2012 to 2013 averaged about $1.40 higher than the uniform milk price for the Upper Midwest Federal Milk Marketing Order. The premium has trended lower since then, with the All-Milk price averaging 5 cents less per cwt. when compared to the uniform price of January to August of 2022. The premium spiked higher in 2020 as cheese plants depooled milk, which depressed the uniform price. While much of the Class III revenue was still paid back to farmers, it was just outside of the pool.

So, the estimated farm gate premium is down about $1.45 per cwt. over the past 11 years. The cost of processing dairy products has climbed by 75 cents to $1 per cwt. over that time frame, which could explain a big portion of the estimated decline in premiums. Commercial buyers could be pushing back at over-order premiums over time to make up for the higher processing costs and other market-related factors.

I should point out that there could be other factors driving down the premium. For much of the 2012-to-2022-time frame, there was a lot of surplus milk in the region, which would also help to drive down the premium. It’s also possible that smaller specialty cheesemakers, who could afford to pay a premium for the milk, have shut down, or at least a greater proportion of the milk in the region is now going toward bulk commodities where there is less premium available.

There are a mix of factors that have driven down the estimated premium. But I’ve done the calculations for New York and Texas and found $1.55 and $1.10 per cwt. reductions for premiums in those states as well. The decline in premiums doesn’t seem to be due to a local oversupply of milk in Wisconsin or a shift in what types of products the milk is going into; it looks like a broader issue than that.

The Federal Milk Marketing Orders need updates to address the current issues and the future of the industry. Make allowances are almost surely going to be raised, which will lower the minimum class prices. However, it’s possible cooperatives will be able to push harder to get some of that money back in the form of higher over-order premiums.