The unprecedented dairy boom of 2022 gave way to the inevitable bust in 2023. Although no one expected sky-high milk prices to persist into this year, the speed and severity of the setback blindsided dairy producers. Class III milk slumped to $13.77 per hundredweight (cwt.) in July.

At the same time, global trade slowed. Sharp inclines in Chinese milk production and a hefty whole milk powder (WMP) stockpile allowed Chinese buyers to take a big step back. From January through July, Chinese WMP imports plunged to their lowest level since 2016. With their primary customer on the sidelines, exporters in New Zealand sought new markets and slashed prices to keep product moving, displacing milk powder from Europe, South America, and the United States. WMP values fell to a seven-year low at the Global Dairy Trade auction in August. Kiwi processors shifted milk away from WMP into skim milk powder and butter, depressing prices for those products as well.

Fortunately, Mexico’s appetite for U.S. dairy remained robust. In the first half of the year, the United States sent 25% more dairy products south of the border than it did during the same period in 2022.

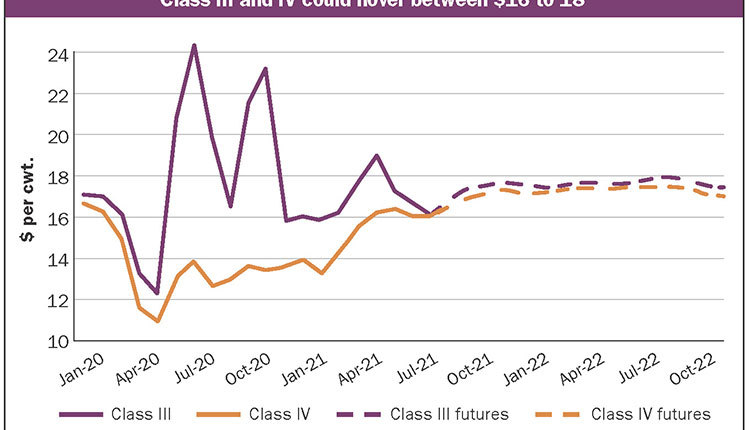

Domestic demand also impressed. In the first half of 2023, Americans consumed 0.9% more cheese, 7.1% more milk powder, 8.7% more butter, and 10.6% more whey than they did last year. Formidable demand for milk powder in North America and a stubbornly strong butter market helped shield Class IV prices from the worst of the declines seen abroad, but they did not escape unscathed. After scoring an all-time high of $25.83 in June 2022, Class IV dropped to $17.95 in April.

Today, the futures are hovering in the $18 to $19 range. That’s better than what might have been, but it does not herald a swift return to prosperity on the farm. Further recovery is likely in 2024, but it will depend on some combination of slower U.S. milk output and stronger export prospects.

Questions about dairy exports

The outlook for global dairy exports is murky. In Europe, consumers are feeling the pinch of higher prices. Europeans are spending 14% more on groceries than they did at this time last year. They’re paying more for other goods, too, and family budgets are strained. Some shoppers may be forced to buy less cheese and butter than they would like. If European dairy demand falls short, European exporters will aggressively pursue other markets.

Dairy exporters in South America, including Argentina and Uruguay, have thrived thanks to strong demand from Brazil. But Brazilian milk production is on the rise, and imports are expected to wane. Argentina and Uruguay are already dropping their milk powder prices, hoping to attract new buyers.

In New Zealand — and in the dairy industry at large — everything depends on China. China’s population is aging and shrinking, suggesting incremental declines in dairy demand. The economy looks feeble, with burdensome household debt, alarming levels of youth unemployment, and shaky consumer confidence. That’s likely to limit Chinese dairy imports in the short term.

On the other hand, Chinese milk production is growing at a slower clip than it did in 2020 through 2022, and China has likely dug into its WMP stockpiles. Chinese dairy consumption per capita has room to grow significantly. In the long run, Chinese demand for dairy is expected to climb more quickly than Chinese milk production, creating opportunities for exporters.

Fewer cows in the U.S.

The outlook for U.S. milk production is more straightforward. The industry is awash in red ink, and the dairy herd is shrinking. Milk output fell short of year-ago volumes in July and likely in August, too.

This summer, dairy profit margins dropped to their lowest levels in more than a decade. In places where feed costs were especially high or where regional surpluses cut deep into milk checks, many producers suffered greater losses than they did in 2009. The markets screamed at dairy producers to boost cull rates, and record-setting beef prices amplified the message. The beef industry is short of cattle, which will support dairy heifer, cull cow, and calf values throughout 2024 and into 2025.

Lofty beef prices are trimming the dairy herd from both ends. Adjusted for seasonal trends, dairy producers are frequently sending more cows to slaughter than they have since 1986, when the government paid producers to cull their cows and exit the industry. Soaring beef values have also pushed dairy producers to create more crossbred beef calves and fewer dairy heifers. U.S. dairy heifer head counts have fallen for seven straight years, and they’ll drop again in 2024.

The milk cow herd is shrinking, and it will continue to do so until on-farm margins recover. It will be a long time before U.S. dairy producers have the appetite — or the capital — to expand. Even then, tight heifer supplies will limit growth.

Tough times around the world

Foreign dairy producers are also feeling the strain of elevated expenses and falling revenue. European milk output is holding above year-ago levels, but pay prices are in retreat and milk collections top last year’s volumes by increasingly slim margins. While milk yields are up, cow numbers are dropping year after year. In New Zealand, it’s too early to draw conclusions about the 2023-24 season, but producers are discouraged by several cuts to forecasted pay prices and increasingly strict environmental regulations.

Pain on the farm has set the stage for slow growth — or perhaps outright declines — in milk production among the world’s major dairy exporters. This suggests that milk and dairy product prices will hold well above the painfully low prices that plagued the industry this summer.

If Chinese demand falls short of the market’s already low expectations, milk prices will likely take a small step back from today’s uninspiring levels. But if Chinese imports start to climb, or if other importers pick up the pace, both Class III and Class IV values could shoot upward.

Dairy producers have endured a long, hard year. The next one promises to be much, much better.