The global milk production shortfall has already stretched on far longer than a typical downturn. High prices usually prompt a recovery in milk output in a six-to-nine-month window. But the current deficit is nearing the one-year mark with no end in sight. Economics, politics, and weather all have contributed substantial barriers to growth, and a swift recovery in milk output is unlikely.

A region by region look

U.S. dairy producers face headwinds as well. Sky-high feed costs are cutting deep into revenues. Feed expenses are particularly painful in the West, where drought and pricey freight have created steep local markups. In the Central Valley of California, hay prices are running at all-time highs — around $450 per ton. High fertilizer costs suggest that crop prices will remain lofty into next year.

All around the nation, thin — and in many cases negative — margins have sapped dairy producers’ ambitions to expand, and milk cow numbers are stagnant at just over 9.4 million head.

Long on limitations

Even if dairy producers want to add cows, they may find it difficult to locate a site with enough farmland or water to support a new operation. They will also have to contend with increasingly onerous state regulations, the notoriously slow permitting process, hefty construction costs, a snarled supply chain, and a tight labor market.

Perhaps more importantly, they’ll need to find a cooperative or processor willing to take on new milk. In much of the country, dairy processing capacity is filled to the brim, and many dairy producers are capped by strict supply management programs.

If dairy producers find a market for new milk and a place to expand, they will have to pay a handsome price for the heifers to fill it. For years, high beef prices and low dairy cow values have pushed more and more producers to breed a share of their milk cow herd to beef sires, creating fewer dairy calves. In the year to come, the beef industry is likely to pull more dairy heifers into feedlots and away from milk parlors as they restock pastures after this year’s drought.

USDA estimates there were 2.8 million dairy heifers expected to calve and enter the dairy herd on January 1, 2022, the smallest inventory since 2005. Biology and economics suggest there will be even fewer dairy heifers next year.

If milk prices are high enough, dairy producers will lower cull rates and boost milk output despite low heifer supplies. But the smaller herd will ensure that the U.S. dairy industry will expand more slowly — and at a greater cost — than it would if heifers were plentiful.

Long on cheese

With all of these barriers to expansion, growth in milk output is likely to remain modest over the next 12 months. But there will still be plenty of cheese. In Europe, processors are directing all the milk they can to cheese vats to prioritize domestic dairy demand.

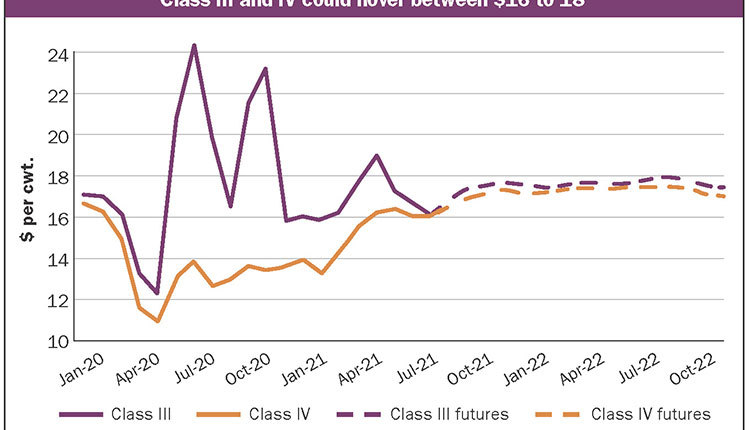

In the United States, cows have moved into the cheese states, and it shows. Through July, U.S. milk output was 0.6% smaller than the first seven months of last year, but cheese production was up 2.7%. Another major cheese plant is poised to begin cranking out Cheddar next spring. In the year ahead, cheese and Class III prices will be vulnerable to setbacks due to oversupply, especially if U.S. cheese exports slow from their current record-shattering pace.

Formidable cheese output will result in heavy whey production. Here, too, exports are critical. After a slow start early this year, U.S. whey shipments to China are on the rise. But if China’s economy slows down, Chinese whey imports could, too. Whey prices are likely to continue their plodding recovery from the August lows, but dairy producers should not expect a return to the unsustainably high prices seen earlier this year, when spot whey traded north of 80 cents per pound.

With more milk going to cheese and whey, U.S. milk powder output is likely to remain healthy but not burdensome. Demand is in question. China imported milk powder at a breakneck pace for 18 months, but imports began to slow this summer. The market assumes they will remain low, and milk powder prices have retreated accordingly. However, inexpensive milk powder may tempt China to ramp up its purchases once again. Milk powder prices will zig and zag, moving quickly up or down at the merest hint that China’s appetite for foreign dairy products is shifting.

Butter is tight, tight, tight

Butter is in short supply as the market heads into the holiday baking season. With grocers anxious about empty cases, CME spot butter leapt above $3 per pound in August and held there in early September. Butter is likely to remain pricey, but it will fall back from these astounding highs as sticker shock dampens consumer demand and imports boost supplies. The futures forecast that butter will drop from $3 in September to around $2.50 in January. That’s good enough to keep Class IV futures well above $20 per hundredweight, but it puts $25 milk out of reach.

The global milk production deficit will continue to make room for U.S. exports and keep a firm floor under milk and dairy product values. But concerns about demand — particularly when consumers are struggling with high prices for many items — will likely keep rallies in check.

Meanwhile, on-farm expenses are likely to remain lofty. Dairy producers should take a hard look at their costs and use Dairy Revenue Protection (DRP) insurance or futures and options to lock in profit margins when they are available. It’s going to be another volatile year in the dairy markets.