The author is a market analyst for the Daily Dairy Report.

What happens when an irresistible force collides with an immovable object? The dairy industry is attempting to solve this classic physics paradox. In this case, the force is the invisible hand of the market.

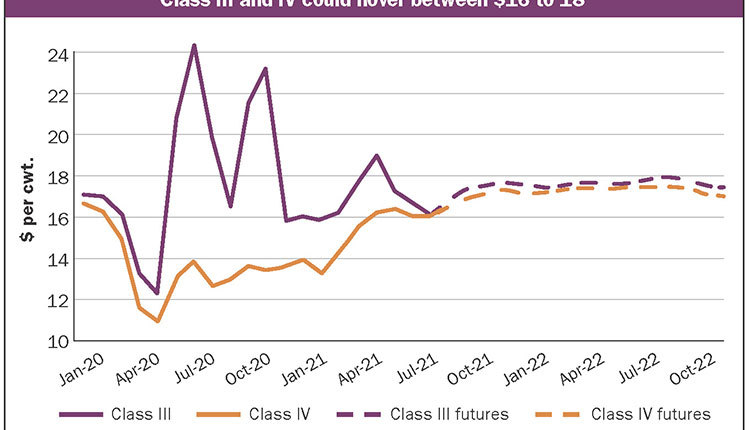

The futures predict that both Class III and Class IV milk will average around $22.30 per hundredweight (cwt). in the fourth quarter of this year, a level that producers find irresistible. They are doing everything they can to make more milk. But their best efforts are falling short, confounded by the heifer shortage, the industry’s frustratingly immovable barrier to expansion.

A numbers game

U.S. dairy heifer inventories stand at the lowest level in decades, and there is simply nothing dairy producers can do to speed up biology. Even if they were to breed fewer beef calves and more dairy heifers, it would take three years to go from a change in breeding practices to an increase in the number of mature heifers ready to enter the milk parlor. There is no sign that producers are making this shift, and high beef prices argue against it, ensuring that any climb in U.S. milk output will be gradual and hard won.

Amid the worsening scarcity of young stock, dairy producers have lowered cull rates to keep their barns full. From September 2023 to August 2024, U.S. dairy producers sent 380,000 fewer milk cows to the packer than in the previous 12 months. That was enough to stabilize the herd, but it was not enough to boost head counts or milk output.

The U.S. dairy herd is older and less productive than it would be if heifer supplies were adequate and cull rates were normal. Avian influenza has also taken a punishing toll on milk production, and now that it has reached California’s Central Valley, additional losses are likely. U.S. milk production has fallen short of year-ago volumes for 13 straight months, and milk yields have dropped below prior-year levels in seven of the past 12 months, an unprecedented setback in U.S. efficiency.

In January through July of this year, the U.S. dairy industry made 0.9% less milk than it did in the first seven months of 2023. But through selective breeding and feeding, dairy producers managed to boost butterfat production. Sky-high component levels pushed butterfat output up 1.7% year over year. Modest improvement in protein content lifted January through July protein output by 0.1%. But nonfat solids output dropped 0.5% and other solids production fell 0.8% compared to 2023.

The international picture

Across the Atlantic, similar milk production trends are starting to take shape. European milk collections topped prior-year volumes in the first half of the year, but now the weather and a livestock virus are dragging milk output downward. Insect-borne bluetongue disease is plaguing herds in Western Europe. There are also concerns about forage quality after a soggy spring. Lower head counts, disease pressure, and poor feed have begun to reduce milk output and component levels, especially for butterfat. European butter prices stand at all-time highs, around $4 per pound. European cheese, whey, and milk powder prices are also on the rise.

In Oceania, milk production is off to a strong start in the offseason, but the weather will be the ultimate arbiter. In Argentina, milk output is well below year-ago volumes but starting to recover. Combined milk output from the world’s five largest exporters has fallen short of year-ago volumes every month since August 2023.

That deficit had a powerful impact on milk prices, providing a firm floor under the dairy markets. But for the past two years, the effect has been muted by a steep decline in Chinese imports, which imposed a relatively low ceiling for most dairy product prices. Chinese milk output grew at an average pace of 6.4% from 2019 to 2023. Amid demographic decline and a slowdown in consumer spending, that was more than enough to keep up with domestic demand growth. China backed away from the global dairy markets in 2022 and imported very little milk powder in 2023 and early 2024. Through July, Chinese milk powder imports stood at their lowest level since 2016. The lack of Chinese purchases forced dairy exporters to compete fiercely for marketshare, despite their sustained milk production deficit.

But milk production among the major exporters has been low enough for long enough that dairy product inventories are getting tight, and prices are climbing to multi-year highs. There are also hints that China may be returning to the global marketplace. USDA’s analyst in Beijing predicts that Chinese milk output will grow just 1.3% this year, and Chinese buyers have been more active at the Global Dairy Trade auctions in August and September. Any increase in Chinese dairy imports would spark a huge rally in dairy product values, especially for milk powder.

Barriers remain

Today, even without a significant uptick in Chinese dairy purchases, CME spot nonfat dry milk and Cheddar blocks stand at their loftiest peaks in nearly two years. The futures forecast milk at $19 per cwt. or higher as far as the eye can see. In a normal dairy boom-and-bust cycle, these high prices would foster painfully low prices in the relatively near future. But there are numerous barriers to expansion in key milksheds around the world. The heifer shortage, disease pressure, high interest rates, and environmental regulations will continue to hamper growth, providing a steady diet for the bulls.

There is a limit, of course. Sticker shock will throttle demand, especially if the global economy suffers a recession. American consumers are weary of inflation and laden with debt. Their spending power is finite. The dairy markets — and insurance strategies like the Dairy Revenue Protection program — offer U.S. dairy producers the rare opportunity to lock in profitable margins for the foreseeable future. Producers should be cautious about selling milk outright in such a volatile market, but they would be wise to purchase floors in case demand disappoints. In the battle between the invisible hand and the heifer shortage, I’m counting on the markets to find a way to balance dairy supply and demand.