For nearly two years, U.S. dairy producers have been building new facilities or crowding more cattle into existing pens. Collectively, they added almost 200,000 milk cows between July 2019 and May 2021, when the number of U.S. milk cows ballooned to a 27-year high.

At the same time, producers were also adopting better management practices, improving their facilities, and investing in genetic advancements. This combination sent milk yields and component levels climbing. It all added up to a flood of milk.

But growth is beginning to slow.

In much of the country, dairy producers have trimmed their herds due to supply control restrictions established by milk processors and co-ops alike. The protracted permitting process, ongoing supply chain struggles, and sky-high cost of building materials will deter — or at least delay — construction of new facilities. Already, cow numbers are starting to slip, and contraction could continue for several reasons.

market analyst for

Daily Dairy Report

First, historically high feed and labor costs are reducing on-farm margins, particularly in the West, where one of the worst droughts ever has withered forage supplies. The ongoing shortage of containers and trucks has added not only to the headaches but also to the price required to import feed.

Second, income is down. After 2020’s government largesse, payments are drying up.

And finally, soaring beef prices have encouraged dairy producers to take a second look at their less productive cows. Since May’s peak, the milk-cow herd has fallen by 9,000 head, and it is likely to shrink further.

Still, there are 9.5 million highly productive cows giving milk in the United States every day. To absorb all that milk, the industry has recently invested enormous sums into expanding cheese production capacity. As a result, cheese output has soared to all-time highs and shows no signs of slowing. Butter production is running only a little behind 2020’s frantic pace. Overall, big production and burdensome inventories will likely keep cheese and butter values in check.

Thankfully, demand is healthy.

Most students are back in the classroom. Once again this year, all of them will qualify for free lunches with a carton of milk. The school milk program will likely lap up more milk than it has in years past, leaving less milk for other uses.

Americans are eating plenty of cheese, butter, and cream-laden meals at restaurants, even if they have to wait patiently for service. And they’re still loading up their grocery carts with more dairy than they did before the pandemic. Exports are booming, too, providing a vital outlet for U.S. whey and milk powder.

Overseas growth in milk output appears limited. In the first half of this year, European milk collections were just 0.5% greater than in the comparable period in 2020, and growth in New Zealand will be restricted to gains in milk yields. There simply isn’t enough pasture to add a lot more cows on the islands.

The China card

While China continues to strive to expand and modernize its dairy industry, demand there continues to outpace supply. Across every major product category, Chinese dairy imports are record large. The trade is concerned that some of these purchases are piling up in warehouses, which could reduce Chinese imports in coming months. But for now, China is still buying, and that has helped clean up the world’s stockpiles of milk powders. If Chinese demand persists, U.S. milk powder exports could also remain strong, helping keep a high floor under the nonfat dry milk market.

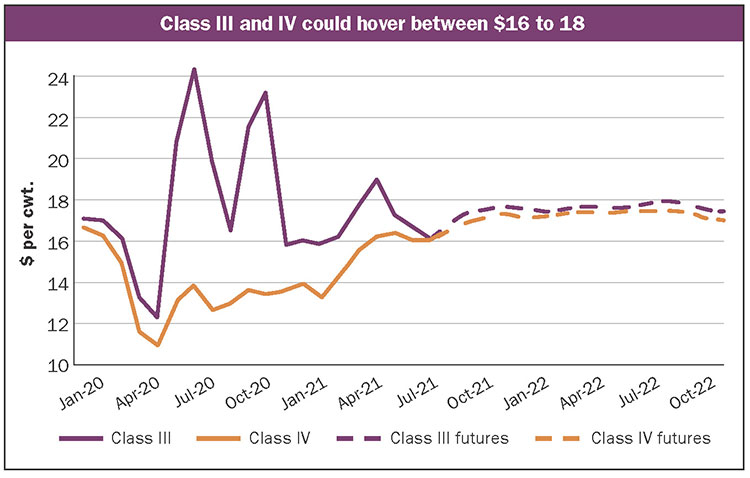

Currently, futures are forecasting that both Class III and Class IV prices will hover between $16 and $18 per hundredweight for the next year or longer. These values are low enough to encourage demand and discourage overproduction. At the same time, $16 to $18 simply won’t pay the bills for many producers, especially while feed remains pricey.

The year to come could be a bit of a slog. Class III suppliers will face steep drops in income. But for those who depend on Class I or IV milk prices, the next 12 months could be significantly better than the past 12.