The author is an economist with the American Farm Bureau Federation.

February was a big month for USDA data releases. The annual first look at net farm income expectations for the year was published, as was the long-awaited 2022 Census of Agriculture. Unfortunately, neither report provided a sunny forecast for the farm economy.

On the farm income side, a record drop was predicted, down $40 billion, or 25.5%, between 2023 and 2024. A $21 billion expected slide in cash receipts for agricultural goods paired with a $17 billion expected rise in production expenses explains 95% of the forecast decline. Receipts for dairy products and milk are expected to be down $921 million (2%), going from $46.4 billion to $45.5 billion.

Consolidation continues

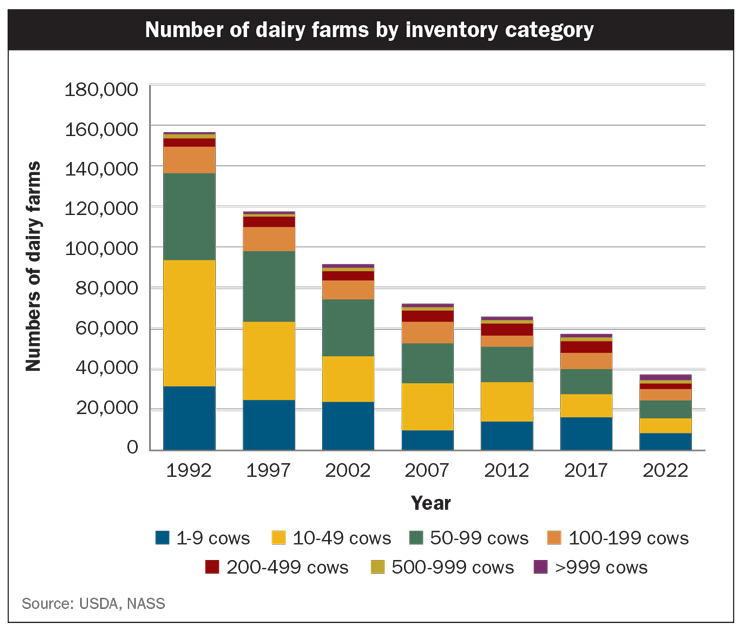

The Census of Agriculture revealed further concentration across the broader farm economy, with a loss of over 140,000 farms between 2017 and 2022. The percentage drop in total dairy farms during the same period was a much larger 34%, translating to 18,500 fewer U.S. dairy farms.

The number of farms with milk cow inventories of over 2,500 head, however, grew 17%, or 120 farms, while the number of farms with inventories between 50 and 499 cows dropped 39% or nearly 9,000. The trend of these statistics is likely not a surprise to anyone, though the magnitude of change in a five-year period may be more notable.

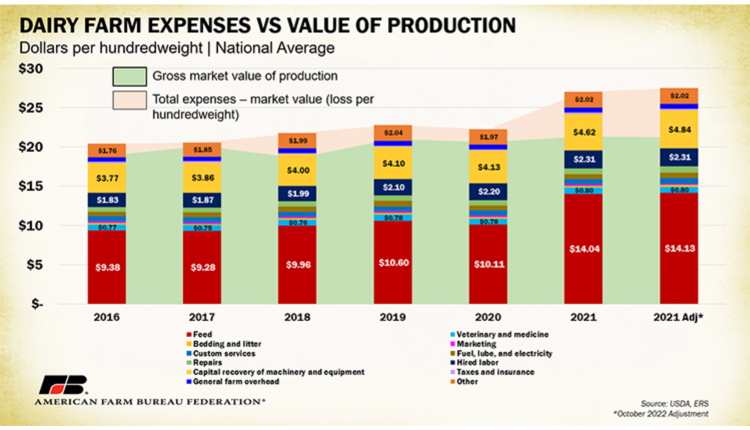

The expense side of the balance sheet for dairy farmers keeps growing, with much uncertainty about whether the price side of the equation will create some wiggle room. Production expenses are estimated to grow 4% over 2023 for a total of $455 billion across the farm economy. This marks the sixth consecutive year of production expense increases and the fourth consecutive year production expenses hit a new record high. The largest percent changes between 2023 and 2024 are expected for marketing, storage, and transportation (up 12%) and for labor (up 7.5%).

USDA expects feed costs to tick upward in 2024 by about a percent. Costs for soybean meal and blended premium alfalfa hay remain above the 2020 to 2022 three-year average with hay up $40 a ton (14%) over the three-year average and soybean meal up $50 a ton (11%) as of December 2023.

Inflation remains high

Even with improving inflationary conditions, interest expenses are expected to be up $230 million (about 1%), meaning relief around the cost of capital and servicing that capital is not expected for much of 2024. The Federal Reserve has held the federal funds effective rate at 5.33% since August 2023 with indications that lower rates could be many months away. High-cost environments push dairy farmers to be more and more reliant on economies of scale or cost savings associated with growth in outputs, a reality reflected in our new census data.

This climb in production costs pairs with regulatory and legislative uncertainty to create many unknowns for dairy farmers and their milk checks. Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) enrollment for 2024 was delayed until February 28. DMC payments are triggered when margins are at their worst, and timely payments are critical to help farmers manage those bad times.

Last year’s political dynamics resulted in an extension of the 2018 Farm Bill and its statutes rather than a new farm bill. A new farm bill is expected to include marginal increases in flexibility for production history and cap levels under DMC as well as improved processor cost transparency requirements that can be used to inform more accurate calculations within the Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) system. Though passage of a farm bill should be top priority for Congress, much uncertainty remains surrounding when it will occur and by whom.

The public hearing segment of the FMMO amendment process ended January 30, but many months of rulemaking and stakeholder commentary remain before dairy farmers vote on any final rule from USDA. What and by how much USDA decides to change FMMO pricing regulations can have significant impacts on dairy farmers’ checks. Not to mention referendum votes from dairy farmers, or their cooperatives, will decide whether changes are accepted or if a federal order ceases to exist.

The American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) has requested one action of certainty from USDA: an emergency issuance of a final rule to return to the higher-of Class I mover. This was the top recommendation of farmers who met at AFBF’s Federal Milk Marketing Order Forum in late 2022, and the change would relieve some negative price pressures on dairy farmers. In a year of uncertainty, such action from Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack would certainly be well received by dairy farmers.