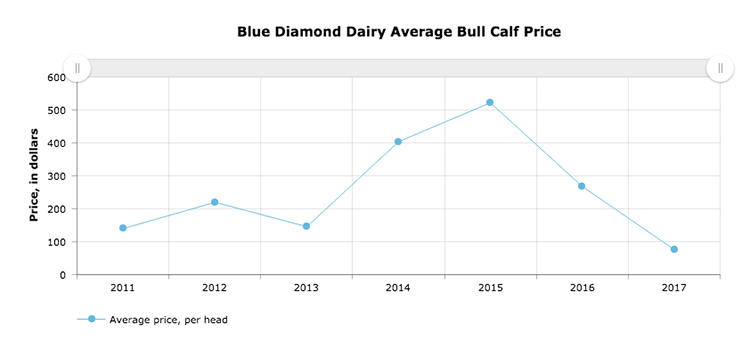

If there’s one thing dairy farmers know well, it’s that when prices go up, they’ll surely come back down. We’ve farmed through peaks and valleys in milk, corn, and hay prices. Now, after an almost unbelievable peak, dairy bull calf prices have hit the valley.

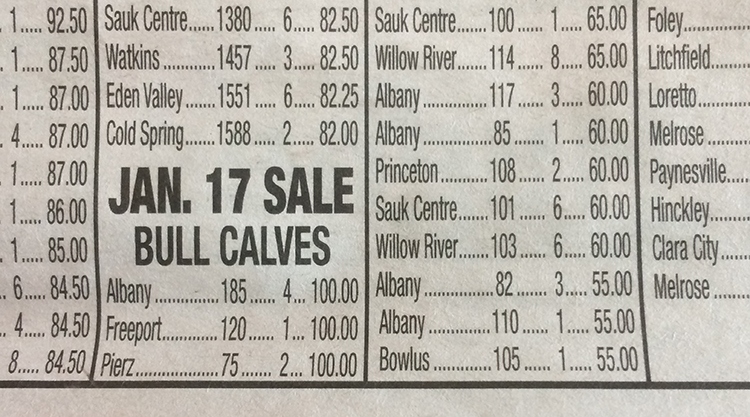

The latest prices for dairy bull calves from our local sale barn made us cringe.

To provide some perspective, 18 months ago we were getting $650 to $700 for 125-pound bull calves. A year ago, the price had mellowed some, but 125-pound calves were still bringing $300 to $350.

I’ll be the first to agree that $700 for a 125-pound bull calf seemed like an outrageous price. On the flip side, though, $50 to $100 seems equally outrageous.

It’s unfortunate that prices for agricultural products overcorrect so drastically.

However, it appears that the decline in dairy bull calf prices isn’t just a result of market overcorrection.

The day after discovering those dismal bull calf prices firsthand, I was perusing the latest issue of Hoard’s Dairyman. Tucked into the Washington Dairygrams was the disgruntling news that Tyson Foods will no longer be buying finished dairy steers for its Joslin, Ill., processing plant. The other two Midwest processing plants will continue to take dairy steers, but the industry can’t lose a third of its processing capacity without experiencing some major ripples.

Rumors are running rampant amongst dairy farmers about why Tyson made the decision to discontinue processing dairy steers.

When I asked Tyson for a statement about the decision, their only response was:

“We continue to harvest Holstein cattle from existing long-term supply agreements. Meanwhile, customer demand continues to drive the direction of our procurement needs.”

I just hope Tyson remembers that finished dairy steers are what kept its plants full after the drought-induced contraction of the finished beef steer supply just a few years ago.

Without finished dairy steers . . .

The result?

Consumers would have paid dearly for beef. Demand for beef would have declined and likely disappeared as consumer preferences switched to pork and poultry.

The author is a dairy farmer and writer from central Minnesota. She farms with her husband, Glen, and their three children. Sadie grew up on a dairy farm in northern Minnesota and graduated from the University of Minnesota with a degree in agricultural communications and marketing. She also blogs at Dairy Good Life.