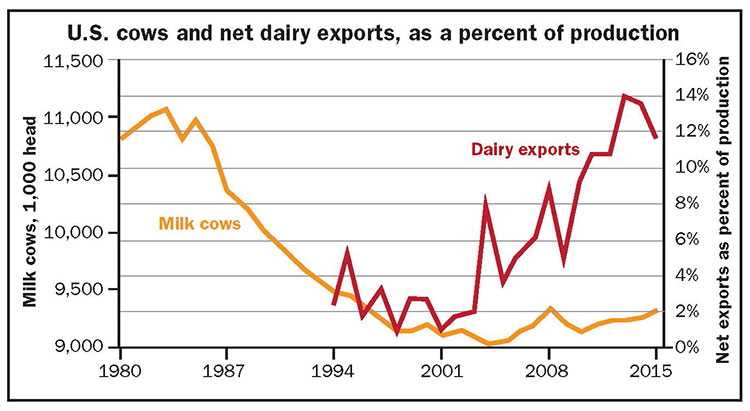

The nation’s dairy herd reached an impressive 9.36 million cows in September . . . a level not observed since the third quarter of 1996. The number of dairy cows has grown by:

- Over 50,000 dairy cows since January 2016

- Over 150,000 since the beginning of 2014

- A full quarter of a million since the end of 2005

This stands in stark contrast to longer historical trends, as the U.S. dairy herd shrunk in size each decade from the end of World War II to 2005. That begs the question, will the next 10 years be more like the last 10, or will the dairy herd size revert to long-term declining trend?

Feeding the nation

The dominant reason for the continuous decline in the dairy herd prior to 2005 was the difference in the growth rate of U.S. population versus milk yield per cow. Over the past 60 years, milk yield was growing at around 2 percent per year, while U.S. population expanded by only 1 percent per year.

In such an environment, the persistent pressure on milk prices can be temporarily suspended in one of four ways.

- The U.S. per capita consumption of dairy products must grow.

- The U.S. government must purchase surplus dairy stocks.

- The U.S. dairy herd must decline in numbers.

- The share of U.S. milk solids exported must expand.

In the six decades prior to 2005, milk market equilibrium was maintained by a combination of the first three channels — shrinking the dairy herd, government purchases (especially in the 1980s), and raising per capita consumption (since mid-1980s). Over the past 10 years, the dairy herd stabilized because of the emergence of the U.S. as a major dairy exporting country. During this time, the U.S. turned a 300 million pound cheese trade deficit into a 400 million pound trade surplus, a difference roughly equal to all of Minnesota’s cheese output. Net exports of total dairy solids doubled four times in 15 years.

Part of the country’s success as a global dairy supplier is due to the surge in international demand that other exporters could not keep up with. Dairy exports may be just 15 percent of U.S. milk solids, but over the past decade, the growth in exports absorbed almost three quarters of all additional milk solids.

The next decade

At the current dairy herd size, average improvements in milk yield per cow of 270 pounds per year result in 2.5 billion pounds of more milk each year, or an extra 25 billion in 2025. Over the next decade, U.S. Census Bureau estimates the U.S. population will grow from 322 to 346 million people. We estimate annual growth of domestic per capita consumption of butterfat to be in the 0.5 percent to 0.9 percent range, while solids-non-fat (SNF) per capita growth is likely to be much lower. Growth of 0.3 percent is our most optimistic scenario, but it could possibly even be negative, down -0.1 percent per year.

These forecasts suggest gains in total domestic demand will more than suffice to absorb all additional butterfat that could be produced by the stable dairy herd over the next decade. However, we are likely to see up to 11 billion pounds of milk-equivalent surplus in SNF.

To keep the dairy herd at 9.35 million head through the next decade, the net exports of U.S. milk solids would have to grow from 10 percent in 2015 to 16 percent in 2025. Using OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) forecasts of global dairy trade trends, this expansion in U.S. exports would require growing our share of global dairy trade from 11 to 17 percent. To understand how daunting of a challenge that is, consider that over the past 10 years United States’ share of global trade rose by only two percentage points, from 9 to 11 percent compared to the previous decade. The OECD projects U.S. export market share to remain stable at 11 percent.

Even if we managed to boost U.S. share of SNF world trade by another 2 percentage points (raising our export volume by 30 percent) by 2025, our dairy herd would still need to shrink by 170 thousand cows for milk supply to equal the sum of domestic and export demand.

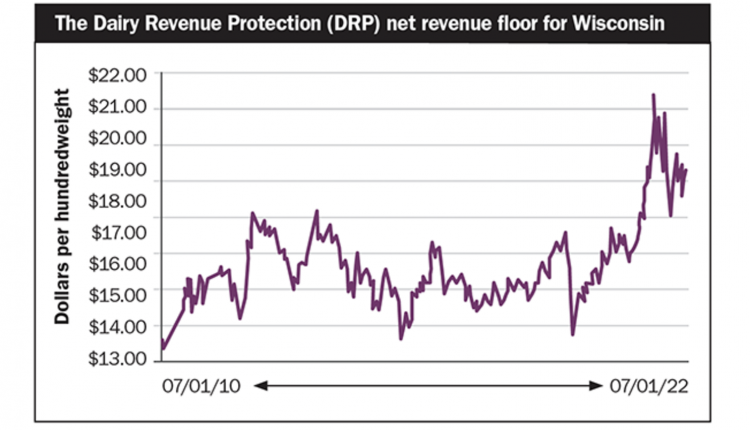

Volatility on the horizon

Absent a major disruption in milk production around the world, in the decade ahead, we are likely to see the return to a slowly declining U.S. dairy herd. This will be induced by steady pressure on milk income over feed costs margins. Since 1980, this pressure has mostly been accomplished by reduction in inflation-adjusted, rather than nominal margins, and the dairy herd reductions were mostly due to retirements and consolidation, rather than severely low prices that justify strong culling or force farm exits due to bankruptcies.

As the U.S. dairy sector consolidates further, and an ever higher share of milk production comes from large operations, price incentives needed to correct the dairy herd size may need to be more acute. As such, we expect the decade ahead to be characterized not just by the secular pressure on income over feed cost margins, but also high volatility. It will be an exciting ride, replete with opportunities as well as challenges. But calm waters are not to be expected.