On the other side of the equation, the U.S. All-Milk price midpoint is projected to be $16.05 per hundredweight (cwt.), down $1.58 from 2017’s price level. If the 2018 All-Milk price comes to fruition, it would be the twelfth highest in history, tying the mark set in 2004.

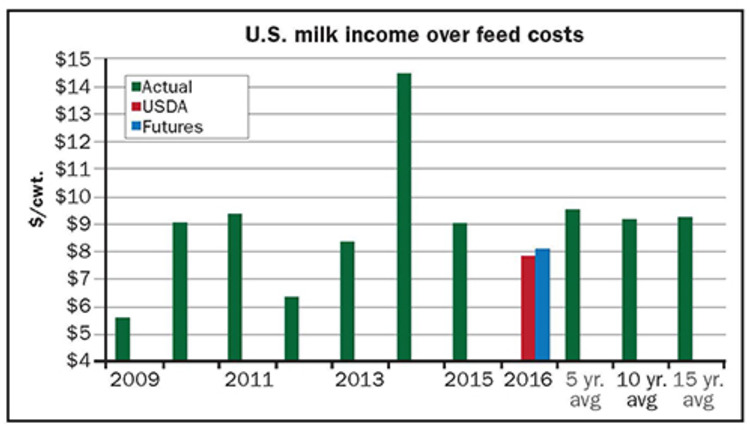

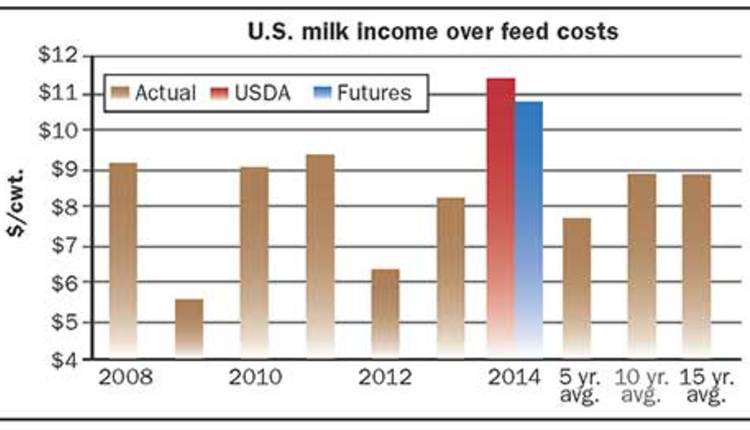

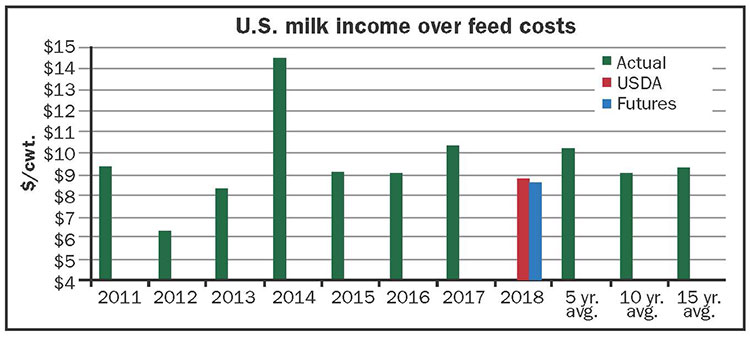

Even with the slight drop in feed costs, the reduction in milk prices pushes income over feed costs for dairy producers to the lowest level since 2013 when income over feed costs averaged $8.35. The general market as represented by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) futures prices are lower than USDA when it comes to dairy producer profitability, with feed prices in 2018 that are higher relative to milk prices.

UNDER THE FIVE-YEAR AVERAGE

Using USDA’s marketing year midpoint projections for corn and soybeans, plus my rough estimate for alfalfa hay, the 2018 feed costs are projected to be $7.24 per hundredweight. When USDA’s feed costs are combined with their calendar year All-Milk midpoint price projection of $16.05, income over feed comes in at $8.81 per hundredweight (see figure). That is $1.53 below 2017’s level of $10.34 and $1.44 lower than the five-year average of $10.25 per hundredweight.

Looking at another source for prices, the CME futures market, the result is very similar. Using the February 14 futures settling prices for corn and soybeans, plus my rough estimate for alfalfa hay, the 2018 feed costs are projected to be $7.78 per hundredweight. When USDA’s $1.50 per cwt. difference between its 2018 All-Milk and Class III milk price estimates are added to the February 14 CME Class III milk price settling futures prices of $14.95, the resulting All-Milk price projection is $16.45. The resulting CME futures price-based income over feed comes in at $8.67 per cwt. (see figure). That is $1.67 per cwt. below 2017’s level and $1.58 lower than the five-year average of $10.25 per hundredweight.

Dairy economist with FCM Division of INTL FCStone Financial Inc.

With U.S. milk income over feed costs estimated to be below average, but above the level needed to keep milk production growing, gains in milk production can be expected to be close to average. That is exactly what USDA is estimating with its projected milk production at 218.7 billion pounds, a gain of 1.5 percent over 2017’s record milk production level. The five-year average growth in milk production is 1.5 percent.

The gain in milk production will probably be more heavily weighted toward the first half of 2018 as opposed to the last half. This will be due to the lagged response in milk production to tighter dairy farm profitability. As profitability tightens, culling of milk cows will climb, resulting in a slowing of growth or possibly shrinking of the dairy herd. Feed quality and quantity for dairy cows may also slow until the 2018 harvest is complete.

With less profitability from the sale of milk, higher beef prices would be welcome by dairy producers. Unfortunately, beef prices look to be unchanged to down slightly from 2017 levels. A larger beef herd is helping to grow supplies and an escalating drought in the Plains states will start to cause more marketing of beef animals in the face of short pasture growth.

HEIFERS EVERYWHERE

The timing of the milk production gains will also be impacted by a decent number of dairy heifers entering the herd this year. Dairy heifers expected to calve in 2018 are pegged at over 3 million head, their sixth-highest level since USDA-NASS started to track the category in 2001.

The inventory level of heifers expected to calve for 2018 shrank even with stronger profitability in 2017. Dairy producers continued to be cautious in the face of tighter economic conditions in 2016 after the record profitability of 2014 was a major factor in the retention of replacement heifers.

According to USDA-NASS’s January Cattle Report, the supply of dairy replacement heifers grew over the past year. Dairy replacement heifers over 500 pounds are estimated to number 4.781 million head, up 0.6 percent from 2017. Of the 4.781 million head of replacement heifers, 3.038 million are expected to calve in 2018. This is 63.5 percent of the total replacement heifer inventory and 32.3 percent of the milk herd.

Last year’s dairy replacement heifers estimate was left unchanged at 4.754 million head, which was 1.3 percent below 2016. The number of heifers expected to have calved in 2017 was also left unchanged at 3.072 million. That placed the heifers expected to calve in 2017 at 64.6 percent of the total heifer inventory and 32.9 percent of the milk herd.

For milk cows that have calved, USDA-NASS estimates the 2018 herd size to be 9.4 million head, up 0.6 percent from 2017. Last year’s milk herd was dropped 3,000 head to 9.346 million head. With the milk herd up the same as replacement heifers, the percentage of replacement heifers to milk cows held steady in 2018 compared to 2017. The 2018 percentage of heifers to milk cows is 50.9 percent, the fourth year in a row and the fifth year ever that the percentage has been over 50 percent.

TOUGHEST SINCE 2013

In general, the 2018 outlook for dairy producers is expected to be the tightest economically since 2013. Profitability is not expected to be drastically below the level to maintain or grow milk production in any one month, but it does look like a year that could challenge most dairy producers’ balance sheets.