The author is a University of New Hampshire extension professor/specialist, emeritus, and an independent dairy consultant in Boscawen, N.H.

Years ago, the barnyard was a common feature on a farmstead raising dairy animals. Before the days of indoor plumbing, there were no water bowls in the dairy stables and the cows were turned out twice a day to drink at a water tub located in the barnyard. With the tied-up style of housing, it was also an opportunity to give the cattle some exercise and check for breeding heats.

When water bowls were introduced to tie stall barns, there wasn’t the need for daily turnout for watering. Later on, freestall housing also provided exercise, so a lot of barnyards were abandoned and either grew over with weeds or became a site for barn expansion.

The right place

There is renewed interest in barnyards, particularly from organic farmers with certification requiring daily access to the elements for all animals above 6 months of age. They are also needed for some farms catering to animal welfare standards in niche markets promoting milk from “naturally raised” cattle.

The barnyard needs to be adjacent to the animal housing to make it convenient for daily turnout. Tie stall barns are more of a challenge than freestall barns because they require a deliberate release time and pretty much an all-out and all-in system. There is also the chore of unhitching and then re-hitching the animals when they return to their stalls. One solution to reduce that chore is to have the cows chained to a tie bar, which can be rotated at the end of the row, so the chain drops off from a hook and an entire section is released at once.

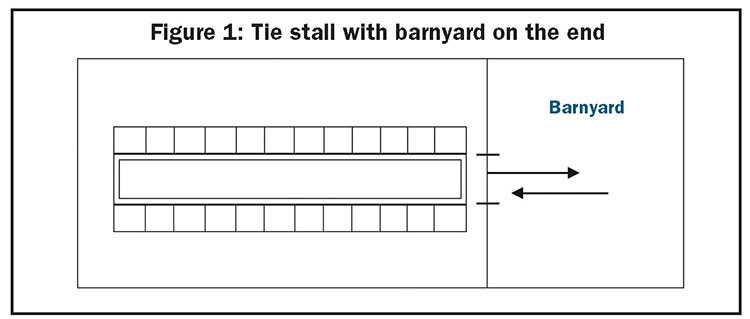

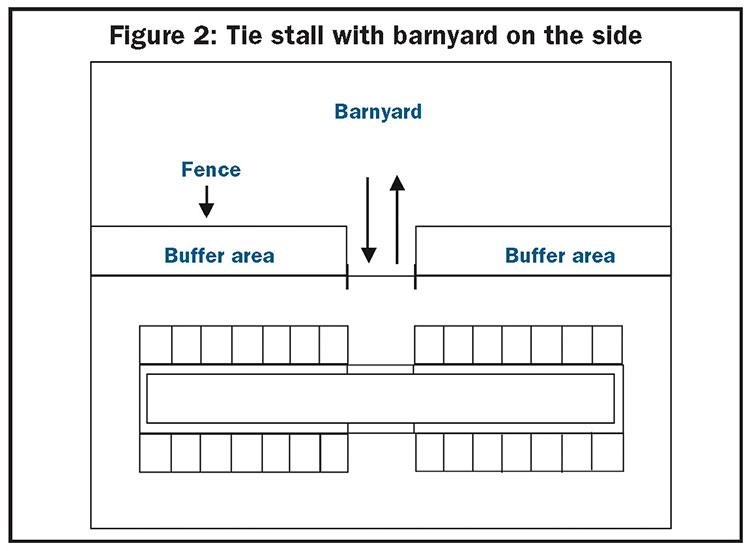

Another inconvenience of a tie stall barn may be that the gutter cleaner deposits manure at the end of the barn where the barnyard needs to be. To avoid possible conflicts with equipment and reduce manure and mud contamination of the cows, it may be advisable to change the gutter cleaner to a side exit if possible or place the yard on the side of the barn (see Figures 1 and 2).

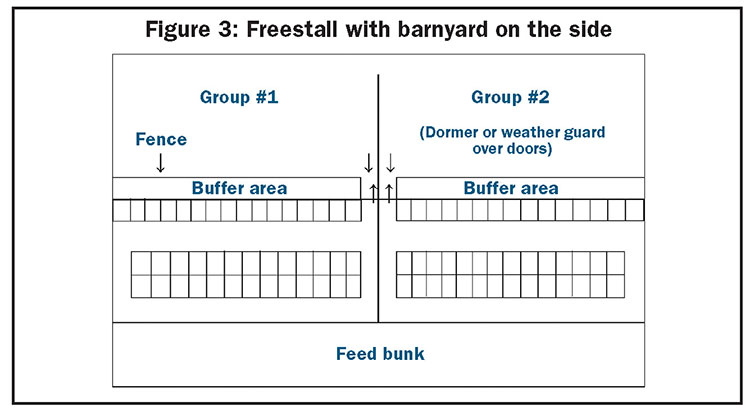

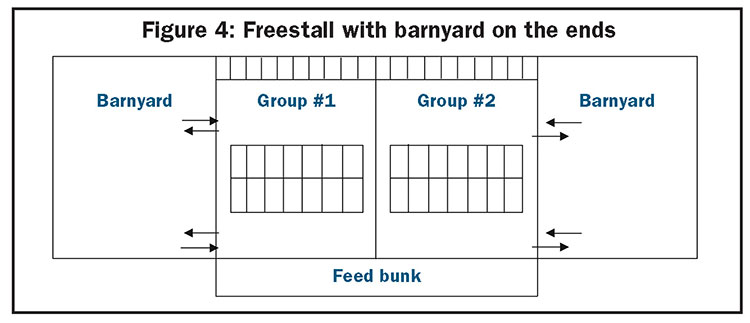

The challenge of outdoor access with freestall barns can be keeping feeding groups separate. Provisions need to be made for exiting the cows out of each end of the barn to a lot, or out the side into two locations with a divider fence (see Figures 3 and 4).

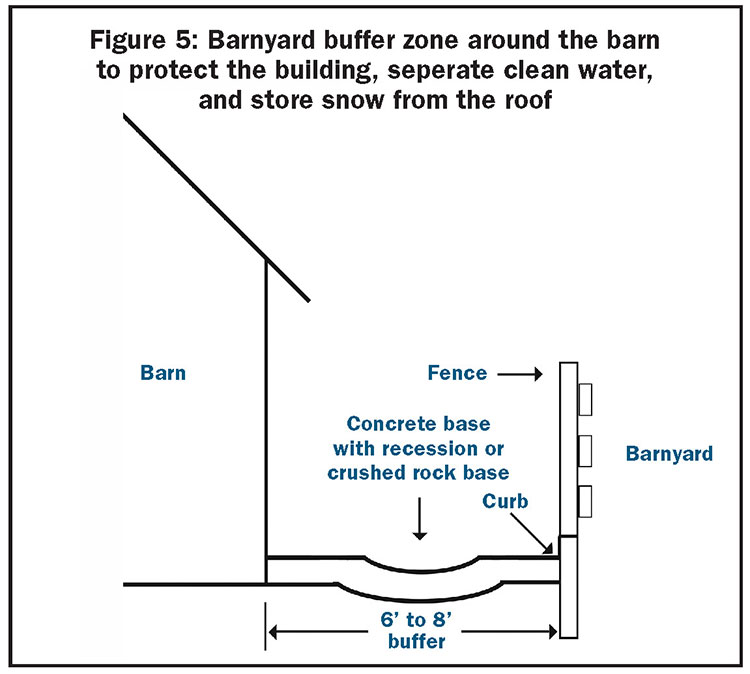

Regardless of the housing type, barnyards which run along the side of the barn should be separated from the barn by a 6- to 8-foot alley to keep the animals away from the building and channel the clean roof water and dirty yard water in different directions (see Figure 5).

A modest investment

The size of the barnyard is determined by the size and number of animals and whether it is a free access situation or an all-out and all-in system. The space requirements for a yard will vary between a minimum of 35 square feet to 50 square feet per animal.

An 8- to 10-inch concrete curb around the edge of the barnyard is necessary to contain the manure and prevent runoff. Rugged fencing around the perimeter of the yard is important because the animals are being confined to a limited space. Also make provisions for a frost-free waterer in the yard.

The concrete floor needs to be a broom finish with commercially cut, diamond-patterned grooves after the concrete has hardened, with a slight slope away from the buildings. This will help minimize slips and falls.

Barnyards may qualify for Natural Resources and Conservation Service (NRCS) grants if they are cleaning up an environmental problem and reducing water contamination. Farmers have found that barnyards not only can improve the environment around a farmstead but can have a very positive effect on breeding, feet and legs, and general herd health. These are relatively modest investments, and some have been built for about $35,000 to accommodate a herd of 150 cows or about $233 per cow.