To be fair, dairy companies and co-ops have had a challenging couple of years, too. Physical traders of dairy products also faced daunting business headwinds. And food companies and restaurants must adapt to changing consumer demands today — some of which don’t include dairy.

I wasn’t raised on a dairy farm, but I’ve come to know that dairy farming is a way of life. No doubt, profit margins and producer patience are running razor thin. And when you have good producers out there asking whether they should even stay in business, you have two things going on:

1. Dire straits for dairy farmers.

2. Typically, the end of a market price cycle.

A CHANGING TIDE

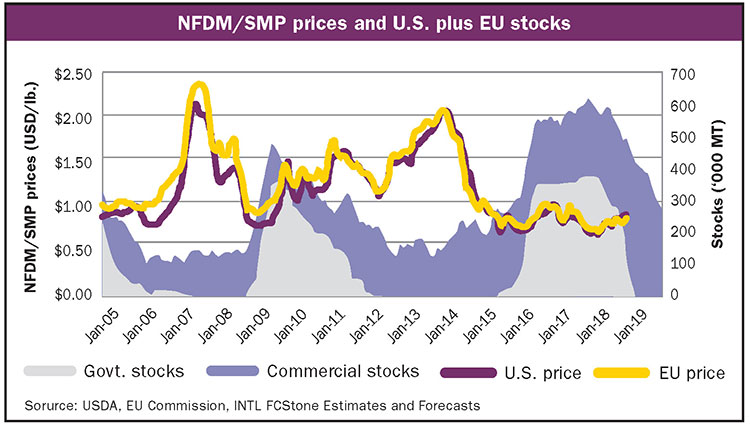

There are countless moving pieces in the global markets to consider, but let’s keep it simple. One major change shows a light at the end of the tunnel: European Union intervention stocks have fallen, and global powder prices are on the mend.

The powder strength is a key driver in having flipped the script on historical Class III/IV pricing skews. Class IV milk prices are trading well above Class III for several months now, and market participants are only beginning to accept that this dynamic can last longer than you’d think. But they ought to be aware that the flip in Class III/IV pricing ordinarily signals something bigger going on.

Strong powder markets do not always predict strong milk prices. In the past, however, we’ve seen rising global powder prices lead the way for U.S. milk prices. In 2007, the drought in Oceania bolstered global powder prices, eventually pushing U.S. dairy prices to over $20 per hundredweight (cwt.). Asian demand in 2013 revealed a short-fall in EU milk production, sending global powder prices skyward. U.S. cheese then spent 11 months of 2014 over $2 per pound.

In the last 10 years, Class IV prices have surpassed Class III 42 percent of the time, which is a somewhat surprising statistic. That percentage drops to 27 percent if you look at just the last five years.

Why is that?

It’s likely because we’ve had excess supplies of milk. This is not much different than what Europe went through, but the questions we ought to be asking ourselves are:

Does Class IV over Class III matter?

If excess milk made more powder, then wouldn’t the opposite also be true?

Maybe.

As of this writing, we haven’t gotten a look at U.S. milk production since November. But at that time — and since then according to anecdotal discussions in the absence of USDA data — milk production was widely thought to be tight in the East and more available out West where we produce the lion’s share of U.S. powder.

If that is the case — and if the price of powder were determined by supplies of fresh milk alone — it would stand to reason that powder prices would be weaker today, and the Class III/IV spread is in a more typical alignment now (given the production skew to powder out West).

But, that’s not the case.

Although the Class III/IV spread is causing some consternation among market participants, the important piece is that the spread is shining a bright light on what I believe is markedly improved Class IV product demand this year. Further, it appears that the Class IV story is beginning to have an impact on U.S. cheese prices by pulling some milk away from the vat.

Cheese is changing There is also a discernible change of tone around available supplies of fresh Cheddar — both 40-pound blocks and 500-pound barrels. What was “heavy” a month ago is now “in balance.” Following a slower 2018 fourth quarter demand cycle, we suggest that Q1 2019 is a launching pad for pipeline refills and firming prices so far this year.If we are in fact slowing cheese production and seeing better demand, we don’t have to wait on summer heat; higher cheese prices makes sense now.

There will be setbacks to escalating market strength seen in Q1. However, from my vantage point, both powder and cheese markets have legitimate upside risk to close out the first quarter and start the second.

Negative sentiment is a sticky thing. It’s why wins pale in comparison to losses . . . just ask Steve Bartman if you don’t believe me. Bartman is the person who deflected a foul ball from the stands in 2003 that may have been caught by a Cubs’ outfielder. With a 3-0 lead in the eighth inning, the Cubs eventually lost 8-3. The incident lived on and was only closed a short 13 years later when the Cubs gave him a World Series Ring in 2016.

Sticky negative sentiment — it’s human nature in dairy markets as much as baseball.

And so, while my views won’t change the business challenges U.S. dairy farmers continue to face, the prospects for better margins and easier stomachs seems to be in the cards for 2019.