These aren’t trick questions. However, the answer is a little trickier than it may sound. The answers also can have implications for the financial decisions you make and how all those decisions made by U.S. farmers collectively add up to impact national milk production.

I’ve lost track of how many times somebody has told me that basic economics doesn’t apply to the dairy industry because dairy farmers produce more milk when prices are high, but they also produce more when prices are low. Despite the apparent contradiction with what economists call the law of supply, this observation is not entirely wrong . . . but it isn’t entirely right either.

A STEADY ASCENT

The national dairy herd declined rather sharply from about 1945 to the mid-1970s, about 5 percent a year. That slowed to roughly 1.5 percent per year from 1970 to 2000. In the new century, cow numbers have bounced around but generally are expanding 10,000 to 15,000 cows each year.

There are two lessons on milk supply here. One, milk production grows faster or slower depending on what happens to the national dairy herd. Given the steady upward push of productivity gains, cow numbers have to come down all that more sharply to slow production growth or cause it to reverse.

Two, it seldom makes sense for a farmer to “understock.” Thus, pulling down cow numbers, or even slowing the growth in cow numbers nationally, means farms go out of business.

IMPACT ON THE LAW OF SUPPLY

When milk prices are high, and not confounded by high costs, there is an incentive to expand that comes from normal notions about a profitable industry. High prices happen when demand is strong or supply is weak. We seldom see big bursts in total production, but if high prices mean high profits, that situation certainly encourages production. Maybe that means overstocking, adding on to the barn, or even building a new one. But, even with strong prices, not many farmers make major investments based on just one good year. There has to be an expectation that dairying will be profitable, on average, over at least the next 10 years.

When milk prices are low or retreating, there are two situations taking place. In the first, profitability is low but not disastrously so for most farms. In this case, some or maybe even many farms will delay culling or overstock as a way to get more cash. This doesn’t mean these management strategies are more profitable. In fact, strategies to simply boost cash often affect longer-term profitability negatively. These are short-term strategies to pay the bills for now.

When prices and margins fall to another, lower level, more farm businesses face serious profitability problems, not just cash availability challenges. This is when we start hearing concern about banks not extending operating credit lines or calling in loans that seem too far below water to rise up again. It’s at these times when we start to see a faster pace in farm exits, either voluntarily or not.

After four years of this long scrape, 2018 proved to be the final straw for 6.8 percent of U.S. farms. This was not because 2018 itself was so catastrophically bad, but rather because the last four years finally took their toll. Milk price, or the combination of milk and other prices, did make a difference.

Milk production started slowing since last October. In March 2019, it actually showed the first annual decline in production since January 2016.

Farmers respond to predictable, long-term profitability by investing and expanding. This is the upside of the law of supply. Farmers who exit the industry when profits are low and hope is drained are the downside of that law.

When farmers overstock, delay culling, delay payments on long-term debt or open accounts, or seek operating loans, they are not trying to bolster profitability, they are trying to improve liquidity — cash on hand, also known as working capital. This is not contrary to the law of supply; because that “law” comes from an analysis of rational responses to changes in profitability, not short-term tactics to increase liquidity.

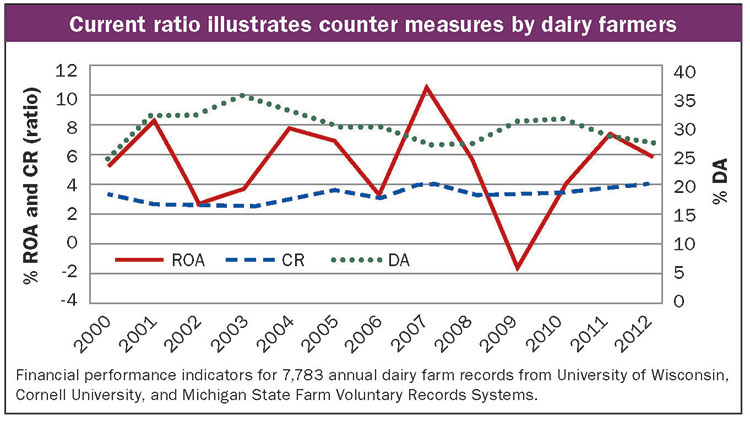

The attached figure comes from a study with my colleagues Chris Wolf, Mark Stephenson, and Wayne Knoblauch. It shows some summary financial performance averages for hundreds of farms in Wisconsin, Michigan, and New York.

Return on assets is a measure of profitability. Debt-to-asset ratio is a measure of solvency. The averages for all these farms bounces around dramatically from high price years (2001, 2004, 2007, and 2011) to low price years (2002 to 2003, 2006, and 2009). But take a look at the current ratio — current farm assets divided by current farm liabilities. That measure of liquidity is much more stable, even in a disastrous year like 2009.

DEEPER QUESTIONS

Does this mean that liquidity, having cash on hand or working capital, is easy? That changes in profitability really don’t have any implications for cash?

You know that isn’t what it means. Rather, what it shows us is that farmers have a tendency to manage day-to-day financial affairs around stabilizing liquidity, even when it is associated with lower profitability.

This is not a contradiction to the law of supply, but it helps us understand why production is so slow to respond to changes in profitability.