In early human history, maps used to show the boundaries of the known world. Beyond those boundaries, there would often be the words “Here be dragons” to indicate potential dangers.

In trying to think about what milk prices may look like in 2021, I just want you to know that my map of the future should have a similar warning. Everything about the pandemic economy is without precedent, and there is no map charting our future navigation. However, there are still a few things that we know and which will likely shape the outcome for the year ahead.

The pandemic

Our safety measures of working from home and social distancing, sanitizing our hands and work surfaces, and wearing masks have helped to slow the spread of the virus. That has given us time to find better pharmaceutical treatments and ultimately vaccines, which will let us get back to more normal routines.

There is talk that we will have a vaccine by the end of the year. It will probably take multiple months before enough vaccine can be made and administered for humanity to have effective immunity and really get on top of the pandemic. However, that vaccine is coming.

If I had to guess, it won’t be until next summer before we really feel as though we can work from our offices and go out to eat without wearing masks any time we feel like it. Personally, I’m looking forward to a Friday night fish fry again.

The aftermath

I am optimistic about ultimately being able to control the pandemic, but what comes afterward? In addition to many business casualties and job losses, the government has spent money like a sailor on shore leave to help folks who need to pay rent and mortgages, put food on the table, and keep businesses viable. We are no longer denominating the cost of government bills in millions or even billions of dollars — we have been talking in trillion dollar units.

In recent years, the annual federal budget has been about $4 trillion. There have been several bills to deal with the consequences of the pandemic including the $2.2 trillion CARES Act, which was largely for economic stimulus.

And, at the time I write this, there is deep debate in Washington about the next stimulus act, which will cost somewhere between $1 trillion to $3 trillion. This is on top of our already $23 trillion national debt. I believe that the pandemic warranted this kind of spending, but there will be repercussions.

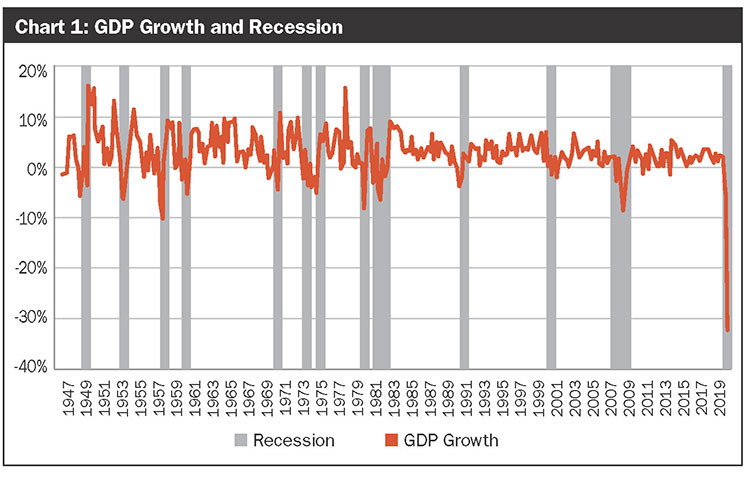

The recession

The U.S. economy is in recession. Typically, recession is defined as two consecutive quarters of negative gross domestic product (GDP) growth. Chart 1 depicts GDP growth over time and the gray bars indicate past recessions. Our normal GDP growth is positive and between 2% to 4%, but when the economy is in contraction, the growth will be negative. It is easy for most of us to remember the impact of the recession in 2008 and 2009 when GDP fell to -8.4% in the third quarter of 2008. But look at where GDP growth is in the second quarter of 2020: -32.9%. This is a level not seen since the Great Depression.

We have learned a lot about managing an economy from the lessons of the 1930s, but we have not been tested to this degree since that time. Much of the deficit spending that Congress has been doing is an attempt to blunt the impact of our current decline, but sooner or later, we have to grow our way out of this trough and pay back our deficit spending.

After the Great Depression and World War II, we had a world that needed to be rebuilt. The U.S. had fought the war effort with an incredible manufacturing surge, and we were ready to create a country better than it had ever been. We built homes for new families, cars to move those people around, parks for recreation, and roads and bridges to get from our homes to these new places.

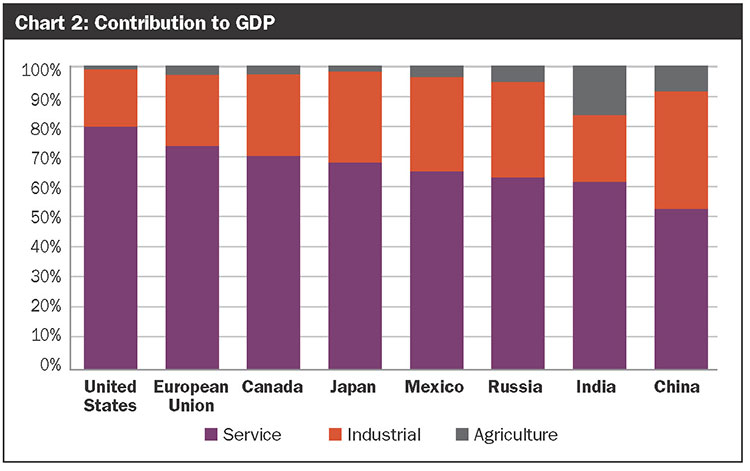

At that time, our economy was heavily influenced by the industrial sector. Today, industry is a much smaller contributor to our overall economy and the service sector dominates.

Services include things like health care and restaurants and entertainment. But many services are consumed from discretionary spending and are among the first things we jettison when our economy heads south. Fortunately for milk producers, food is not discretionary, and most dairy products are very affordable items in the budget. You can see in Chart 2 that agriculture contributes less than 1% to the U.S. economy.

The new normal?

I’ve heard the term “the new normal” so much that I’m tired of it. But, when we think of our postpandemic economy, we can muse about what it may look like. Out-of-home eating has taken a serious hit from which it will take a long time to recover. Restaurants will not be able to pack people in like they did in the past. That’s a problem in a low-margin business. I also suspect that we will continue to prepare and eat more meals at home than we did before the pandemic. Eating out will be more of a treat than an everyday means of getting our food.

The dairy industry will need to meet the consumer where they are, not where we want them to be. If they are going to do more meal preparation at home, then dairy needs to be in the refrigerator waiting to find its way into tonight’s meal. And, if the home cooks are tired of the five or six recipes they’ve perfected while social distancing, then we need to be able to inspire them with some new ideas.

Part of what allowed us to serve the customer when they were “safer-at-home” was a greater volume but smaller choice of products at retail. Fewer stock keeping units (SKUs) at grocery stores may continue in the years ahead, so it will be important to make sure that they are the items that a consumer really wants to prepare meals at home.

What’s ahead?

There may be dragons ahead, but our curiosity and exploration has opened the world to us. I would urge caution to producers in the next couple of years. This may not be the time for big investments until we have a better idea about the dairy economy.

Look for risk management opportunities when the market presents livable prices. I’m sure that we will see pockets of optimism when export sales take a jump. In the long run, the market price always has to cover the costs of production.