The author is a senior associate editor for Hoard’s Dairyman.

Dairy farmers start each new year with anticipation that milk prices will be better than the year before. In the case of 2022, it appears that hope will become a reality.

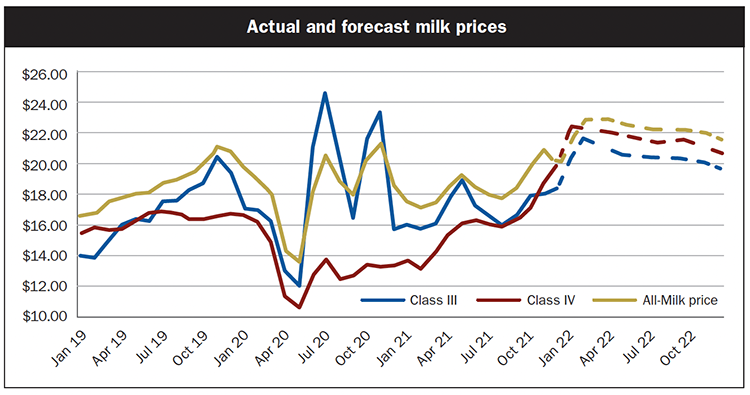

“I’m looking at a pretty substantial increase from where we were last year,” said Mark Stephenson, the director of dairy policy analysis at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, during the January Hoard’s Dairyman webinar.

He estimates a $22 average All-Milk price, which would be $2 to $2.50 higher than in 2021 when the average All-Milk price was $19 per hundredweight. Although there could be some swings due to volatility, he expects the price to remain relatively flat through the year.

There is a catch, though, in the form of elevated input costs.

“It could be a good milk price year, as long as costs of production are not too high,” he explained. “If you have adequate feed in the bunk that you produced and harvested, it might be a decent year.”

In parts of the country where farms tend to purchase more feed inputs, this is where Stephenson said margins will be particularly thin. On the other hand, in places where there is plenty of feed and it is of high quality, it will be attractive to produce more milk.

Even with improved milk prices in the forecast, Stephenson said, “Continue to look at risk management options.” He advised farmers to watch for ways to control variable costs of production and to put a floor under price opportunities when they present themselves.

Production at home

There are several factors influencing the milk price forecast. Domestic demand was the first Stephenson discussed.

“Domestic demand has been good,” he shared, pointing to a continued upward trend that led to 644 pounds of milk equivalent consumption per capita. While fluid milk intake is still on a downward spiral, cheese has gone from 14 pounds per person in 1975 to 38 pounds per person currently.

“The amount of milk we are dedicating to the cheese category has been a real bright star for the dairy industry over a long period of time,” Stephenson stated. There was also growth in the yogurt and butter categories in 2021.

Domestic supply has been impacted by the ongoing pandemic. The end of 2019 brought optimism for 2020 milk prices, so farmers were holding onto cows and the national herd was robust. Then, in March 2020, there was suddenly too much milk and nowhere to sell it with the closure of many schools and restaurants, and many farms faced supply controls imposed by cooperatives or dairy processors. As a response, farms culled dairy cows.

Improved demand later in 2020 pushed up prices, and cow numbers began to build again. Cow numbers peaked in May 2021 at 9.5 million, a number that hadn’t been seen for a quarter of a century. As the year went on, thin margins made it difficult for farms to operate, and Stephenson said dairy cow numbers retreated.

As a result, milk supplies domestically are relatively tight, which Stephenson said is giving optimism for dairy prices in 2022.

Looking abroad

Export markets and competitors also influence domestic milk prices. For 2022, exports are playing a positive role in the price equation.

“Export demand is larger than ever,” said Stephenson. Since 2004, the amount of U.S. dairy products sent overseas has been growing, and last year, 17.5% of dairy solids were exported. “Export demand has been strong, on all dairy products in several categories,” he shared.

He noted that exports to several customers also rose the past few years. China is a notable one, with large gains in 2020 and 2021. Exports to the Middle East and North Africa showed steady growth the last two years as well.

Meanwhile, production has been down for some of our biggest exporting competitors, namely New Zealand and the European Union. The world has been demanding dairy products, but most countries haven’t been able to keep pace, which means these countries are drawing down on dairy product stocks. That signals higher prices, Stephenson stated.

There has been some friction in the export markets, including shipping port congestion. Stephenson said it once cost about $3,000 to send a loaded ship container across the ocean. That climbed to $20,000 when there was severe congestion and high demand for empty containers. More recently, those prices have receded some, to around $12,000 per container.

Although this congestion is improving, Stephenson anticipates it may take a few years to truly resolve. “It’s going to take time to work all of these friction points out of the supply chain,” he said. “It’s not just a dairy supply chain problem; it involves moving all products shipping from country to country.”

Another friction point is the value of the U.S. dollar. While a strong dollar is good when buying products from other countries, that is not the case for our export sales.

Stephenson said that during times of global economic turmoil, the U.S. dollar tends to strengthen. “It is not a problem we can’t overcome,” Stephenson noted, “but our products need to compete based on price and quality.”

Fortunately, Stephenson said that prices of U.S. dairy products are competitive at the current time. Prices for milk powder are always competitive, he said, while cheese, butter, and butterfat are competitive now, but they have experienced more variation in terms of price.

Even with some friction in exports, Stephenson predicts the U.S. will pick up market share again in 2022.

Questions about inflation

It has been a while since inflation was a concerning factor for dairy prices, but the 6.8% inflation rate for November 2021 was the highest seen in four decades. Back in the 1980s, inflation rates climbed into the double digits, and Stephenson said that was very disruptive to the economy. Stephenson sees this as a temporary spike, not a persistent problem, but he noted that inflation levels are still climbing.

In the past, fiscal policy or wartime spending were causes of persistent inflation. Today, there could be a few reasons why. Some point to the stimulus spending to counteract COVID-19 job losses as a source. Stephenson explained that for people who were unemployed, it simply replaced the income they once had and would not cause inflation. However, money received by people who did really need it could be a source of inflation.

Stephenson said if the federal government feels the need to rein in inflation, they will raise interest rates. That makes borrowing money less appealing and saving money more appealing, cutting down on spending.

He also addressed structural causes of inflation. Forty years ago, a structural cause of inflation was a cost-push from energy. Today, the cost-push is coming from labor shortages. Pandemic inspired job changes, dual income houses reducing to one income, and Baby Boomers retiring earlier all combined to reduce the size of the available workforce.

For farmers, Stephenson said to evaluate capital investments carefully. With the labor shortage being a long-lasting concern, he recommended investments in labor saving capital, including automation in milking and field equipment.

Even with some uncertainty in the general economy, Stephenson is optimistic about the year ahead for the dairy industry, but again, it depends on a farm’s input costs and their ability to put some price risk strategies in place.

“Some farms will have pretty good margins, as long as they keep input costs relatively low,” he summarized. To learn more, watch the Hoard’s Dairyman webinar, “The dairy price outlook for 2022: A spotlight on supply, demand, and inflation,” at on.hoards.com/WB_011022.