As recovery from the pandemic continues, it may be years before we understand all of the consumption and production implications. One concept that has received a great deal of attention is “resiliency.” Let’s consider what we know thus far about resiliency in the U.S. dairy industry and what it means going forward.

In the business world, resiliency is defined as the ability of a business to either weather or bounce back from a large disruption. Given that definition, resiliency has two dimensions. Either the shock has little effect on the business and/or the business operations recover quickly from the shock.

Resiliency, in this situation, is related to risk management. The same strategies apply: reduce the impact of adverse outcomes, improve risk bearing capability, or maintain decision-making flexibility.

Resilient supply chains are either minimally impacted by adverse events and/or they recover quickly. When the pandemic hit in March and April of 2020, consumers very abruptly shifted from a nearly 50-50 even split of serving food at home via purchases at supermarkets and dining in restaurants to almost exclusively food at home. As this took place, supermarkets struggled to keep some products in stock as demand spiked while restaurants closed. The effects reverberated through the entire supply chain back toward dairy farmers.

Rocked to the core

Cooperatives and processors that provided food for markets serving meals away from home scrambled to find a way to balance milk supplies. The effects depended not just on the product in question but also packaging, serving size, storage, and inventory options. One result was that a significant amount of milk was dumped in the short-run.

There is always a small amount of milk dumped because of plant disruptions or maintenance, weather, and other events. In fact, 0.4% of milk pooled across all Federal Milk Marketing Orders (FMMOs) was dumped in a typical month from 2015 to 2019. April 2020 was an extreme event where 2.57%, equivalent to 349.9 million pounds of milk, was dumped.

Milk dumped was not evenly distributed across the country. In terms of quantity, the Northeast FMMO handled more than one-third of all milk dumped nationally (131 million pounds), reflecting the dependence on consumption in retail outlets of the region. This represented 5.67% of milk pooled in the Northeast Order for April. The largest percentage of milk dumped occurred in Florida at 14.3%.

An amazing rebound

However, the dumping did not continue very long. In May 2020, the amount of dumped milk declined to 0.27% and stayed within normal bounds thereafter. This response occurred through a couple of mechanisms.

One was a significant reduction in milk production, in many cases spurred by cooperative base-excess programs. Another factor was the ramping up of balancing plants — particularly butter. Thus, in terms of effectively adjusting to provide the market with dairy products in the face of a true “black swan” event, the dairy supply chain proved quite resilient.

Based on this experience, future investments related to resiliency might include storage (redundancy), extended shelf life products (flexibility), and balancing capacity. Providing adequate compensation for the latter remains a challenge in many parts of the country.

There will be ongoing discussions about examining inventory practices and product mix. A key consideration will be to make effective investments while not over-reacting to what we all hope was a once-in-a-lifetime event.

A three-prong answer

At the farm level, the outcome of 2020 depended on three aspects: where milk was marketed, whether risk management programs were in place, and how much government help was received. As was discussed earlier, the pandemic effect was not uniform and depended heavily on which products and outlets were marketed.

At the farm level, this was largely a function of where milk was shipped and the product portfolio at that outlet. American cheese use climbed as home consumption grew. Meanwhile, other products suffered. Many farmers do not have reasonable options available for changing market outlets in the short run, but it is certainly worth considering ways to minimize the impacts of any future events of this nature.

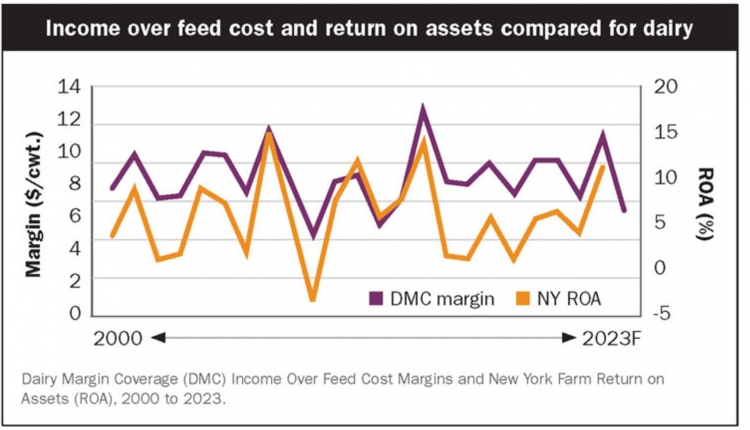

Risk management programs are most effective, in most cases, if consistently applied. The Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) program has the potential to offer significant risk protection, particularly for smaller herds, but only 50.1% of eligible herds enrolled in 2020. Participation climbed to 74.4% for 2021. High feed prices in recent months have resulted in payments, and the program seems like a logical beginning point for many farm risk management programs.

Other risk management programs, including Dairy Revenue Protection (DRP), offered safety. This particularly holds true for farms signed up prior to the unforeseen pandemic. Dairy futures and options markets often offer the potential to protect long-run average margins nine to 15 months out.

Finally, government intervention in 2020, related to the pandemic, came in the form of the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP). These direct payments were tied to milk production levels and payment limits applied in some cases. Meanwhile, the Farmers to Families Food Box Program purchased dairy products for distribution through food assistance programs. This blunted growth in inventories and supported prices. Finally, the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) provided low interest, forgivable loans to support several weeks of payroll. Each of these programs provided relief but were difficult to plan around as the funding and eligibility evolved during the pandemic.

What about this year?

What does the current pandemic situation mean for U.S. dairy markets in 2021? An aspect that is key to continued dairy growth is market outlets that include international customers.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 vaccine has not been widely available in many parts of the world, so recovery in those countries continues to languish. This has implications for international demand as recovery is necessary for continued demand growth. Ongoing weakness in some countries will further dampen demand as economic weakness will translate into exchange rates that likely make U.S. dairy products more expensive.