The author works with Oak Point Agronomics, Hammond, N.Y, and is formerly with the William H. Miner Agricultural Research Institute, Chazy, N.Y.

Miner Institute's dairy operation includes a slurry manure pit with a capacity of over 6 million gallons. The pit is almost 500 feet long, 145 feet wide, and about 9 feet deep. Each spring, we agitate this pit for many hours prior to spreading manure. Even though we have several places around the pit for the agitation and pumping equipment, dropping an agitator into the corner of a pit this size is about as effective as trying to stir a swimming pool full of pea soup with an eggbeater: The equipment just isn't sufficient for the size and volume of the storage.

After agitating for a day or so, the manure appears to be somewhat homogenized, but there's a layer of highly liquid slurry that must be pumped out before we get to the "good stuff." For instance, last year when we started unloading this pit, the results of the first manure analysis, taken in early June, showed barely 1 percent solids. The second analysis, from a sample taken in early August after we'd removed just over a million gallons, was up to 2 percent solids. Another million gallons or so pumped and spread and we were at 3.7 percent solids. Finally, after another 2 million gallons, the solids content had increased to 6.6 percent. And we weren't scraping the bottom of the barrel - or manure pit, to be accurate: When we took this last sample, there was still over 2 million gallons of slurry manure remaining in the pit.

The situation at the Miner Institute dairy is far from unique; other farmers have told us that the first manure they remove from their large slurry pits is very low in solids, with solids content slowly increasing as they empty their storages. Penn State's Agricultural Analytical Services Lab recognizes this fact and offers a reduced price per sample for a manure analysis kit that includes five samples.

The instructions include the following statement: "In many manure storage systems, there is considerable variation in the manure nutrient content even within the storage unit. It is recommended that at least once after a manure storage is constructed, a detailed analysis of the manure be performed to determine the amount of this variation."

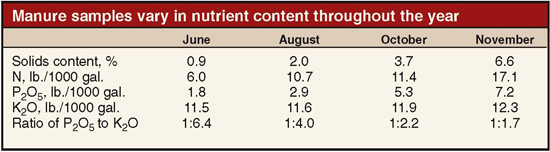

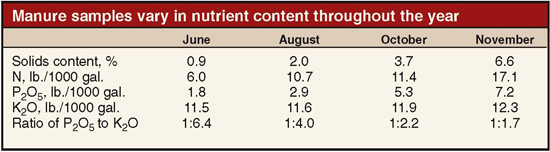

The table shows the analysis of four samples of 2007 slurry manure from Miner Institute's manure pit plus the ratio of phosphorus to potassium.

Note that, as the pit is pumped down and solids content increases, the potassium content of the slurry changes very little, while the phosphate content is progressively greater. This results in the ratio of phosphate to potassium increasing considerably. The first slurry contained more than six times as much potassium as it did phosphate, while the manure removed during the fall (both October and November samples) contained only about twice as much.

Use to your advantage . . .

Dairy farmers can use this "manure pit math" to their advantage. At Miner Institute about half the cropland is within a mile of the farmstead (and the manure pit), while the other half is between 4 and 12 miles away. Almost all of the land that's at least 4 miles away -either leased or recently purchased - is low in P and K. On the contrary, most of the land within a mile of the farmstead has been manured for much of the past 100 years and, not surprisingly, is moderate to high in phosphorus.

The Institute's nutrient management plan (CAFO) allows modest applications of phosphorus on the "home farm" fields, while there's no restriction on potassium rates, and soil tests often indicate a need for this nutrient. Therefore, the home farm fields are the best place for the highly liquid manure - the first out of the pit.

Also, if you had to haul a tanker load of manure 5 miles away, which would you rather haul: a load with 1 percent solids or one with 6 percent solids? Based on recent fertilizer prices, the approximate N-P-K value of Miner Institute dairy manure with 0.9 percent solids is $11.50 per 1,000 gallons, while the value of manure with 6.6 percent solids is $24.50 per 1,000 gallons.

Click here to return to the Crops & Forages E-Sources

0906_409

Miner Institute's dairy operation includes a slurry manure pit with a capacity of over 6 million gallons. The pit is almost 500 feet long, 145 feet wide, and about 9 feet deep. Each spring, we agitate this pit for many hours prior to spreading manure. Even though we have several places around the pit for the agitation and pumping equipment, dropping an agitator into the corner of a pit this size is about as effective as trying to stir a swimming pool full of pea soup with an eggbeater: The equipment just isn't sufficient for the size and volume of the storage.

After agitating for a day or so, the manure appears to be somewhat homogenized, but there's a layer of highly liquid slurry that must be pumped out before we get to the "good stuff." For instance, last year when we started unloading this pit, the results of the first manure analysis, taken in early June, showed barely 1 percent solids. The second analysis, from a sample taken in early August after we'd removed just over a million gallons, was up to 2 percent solids. Another million gallons or so pumped and spread and we were at 3.7 percent solids. Finally, after another 2 million gallons, the solids content had increased to 6.6 percent. And we weren't scraping the bottom of the barrel - or manure pit, to be accurate: When we took this last sample, there was still over 2 million gallons of slurry manure remaining in the pit.

The situation at the Miner Institute dairy is far from unique; other farmers have told us that the first manure they remove from their large slurry pits is very low in solids, with solids content slowly increasing as they empty their storages. Penn State's Agricultural Analytical Services Lab recognizes this fact and offers a reduced price per sample for a manure analysis kit that includes five samples.

The instructions include the following statement: "In many manure storage systems, there is considerable variation in the manure nutrient content even within the storage unit. It is recommended that at least once after a manure storage is constructed, a detailed analysis of the manure be performed to determine the amount of this variation."

The table shows the analysis of four samples of 2007 slurry manure from Miner Institute's manure pit plus the ratio of phosphorus to potassium.

Note that, as the pit is pumped down and solids content increases, the potassium content of the slurry changes very little, while the phosphate content is progressively greater. This results in the ratio of phosphate to potassium increasing considerably. The first slurry contained more than six times as much potassium as it did phosphate, while the manure removed during the fall (both October and November samples) contained only about twice as much.

Use to your advantage . . .

Dairy farmers can use this "manure pit math" to their advantage. At Miner Institute about half the cropland is within a mile of the farmstead (and the manure pit), while the other half is between 4 and 12 miles away. Almost all of the land that's at least 4 miles away -either leased or recently purchased - is low in P and K. On the contrary, most of the land within a mile of the farmstead has been manured for much of the past 100 years and, not surprisingly, is moderate to high in phosphorus.

The Institute's nutrient management plan (CAFO) allows modest applications of phosphorus on the "home farm" fields, while there's no restriction on potassium rates, and soil tests often indicate a need for this nutrient. Therefore, the home farm fields are the best place for the highly liquid manure - the first out of the pit.

Also, if you had to haul a tanker load of manure 5 miles away, which would you rather haul: a load with 1 percent solids or one with 6 percent solids? Based on recent fertilizer prices, the approximate N-P-K value of Miner Institute dairy manure with 0.9 percent solids is $11.50 per 1,000 gallons, while the value of manure with 6.6 percent solids is $24.50 per 1,000 gallons.

0906_409