I don't have the answer, but because exports now account for more than 13 percent of all milk solids made in the U.S. and Class I use is falling as steadily as public approval of Congress, I sure have the question. Here's an example why:

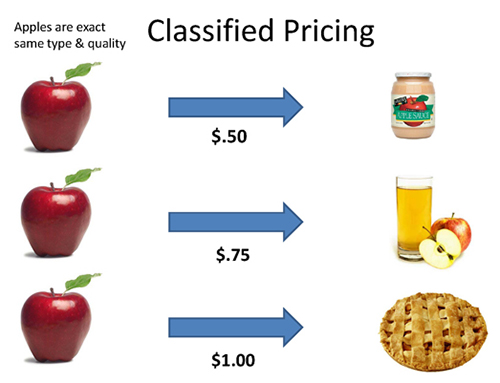

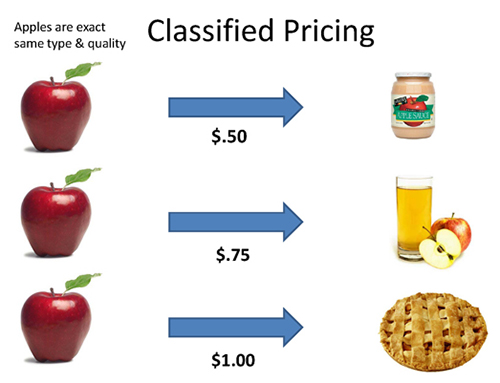

You go shopping at the market. At the checkout stand, Norma holds up your plastic bag of Pippins. "What do you plan to do with these?" she asks.

"What does it matter?" you say. "They're just apples."

Norma glares at you over her bifocals. "No they aren't, honey, and it matters a lot. They're an input material. If you eat them raw, they cost $1.25 per pound. If you make them into a pie, they're $1. If you squeeze them into cider, they're 75 cents. And if you make applesauce, they're 50 cents."

"That's insane. I don't know what I'll do with them, I just want some apples!"

Welcome to classified milk pricing, which makes sense in a way that… well, leaves me totally clueless.

Here in the 21st century, classified or end product pricing is extinct for everything except milk. Milk is still back in the 1890s when classified pricing was created. Today, entrepreneurs look at raw materials that are available, do research, and dream up things to make from them that people will buy. The market votes who wins and loses, supply and demand sets the prices.

The price of apples does not change according to what you do with them. But milk does. Why? Is there a shortage out there that we don't know about? Is forcing people to say ahead of time what they will do with it really a part of free enterprise? Does having three, four or five prices for the same raw product encourage innovation and investment in new products?

If milk were one price, wouldn't the market take care of itself? Would milk find its best and most profitable use? Shortages of some products might occur – but wouldn't they also cause prices to rise and encourage production to shift into making them?

All apples are not the same quality; nor is all milk. Some are worth more than others. But wouldn't cheesemakers and pie makers know this? Wouldn't they find what works best for them? Wouldn't they pay more for what makes them more?

What am I missing here?

The author has served large Western dairy readers for the past 36 years and manages Hoard's WEST, a publication written specifically for Western herds. He is a graduate of Cal Poly-San Luis Obispo, majored in journalism and is known as a Western dairying specialist.

You go shopping at the market. At the checkout stand, Norma holds up your plastic bag of Pippins. "What do you plan to do with these?" she asks.

"What does it matter?" you say. "They're just apples."

Norma glares at you over her bifocals. "No they aren't, honey, and it matters a lot. They're an input material. If you eat them raw, they cost $1.25 per pound. If you make them into a pie, they're $1. If you squeeze them into cider, they're 75 cents. And if you make applesauce, they're 50 cents."

"That's insane. I don't know what I'll do with them, I just want some apples!"

Welcome to classified milk pricing, which makes sense in a way that… well, leaves me totally clueless.

Here in the 21st century, classified or end product pricing is extinct for everything except milk. Milk is still back in the 1890s when classified pricing was created. Today, entrepreneurs look at raw materials that are available, do research, and dream up things to make from them that people will buy. The market votes who wins and loses, supply and demand sets the prices.

The price of apples does not change according to what you do with them. But milk does. Why? Is there a shortage out there that we don't know about? Is forcing people to say ahead of time what they will do with it really a part of free enterprise? Does having three, four or five prices for the same raw product encourage innovation and investment in new products?

If milk were one price, wouldn't the market take care of itself? Would milk find its best and most profitable use? Shortages of some products might occur – but wouldn't they also cause prices to rise and encourage production to shift into making them?

All apples are not the same quality; nor is all milk. Some are worth more than others. But wouldn't cheesemakers and pie makers know this? Wouldn't they find what works best for them? Wouldn't they pay more for what makes them more?

What am I missing here?

The author has served large Western dairy readers for the past 36 years and manages Hoard's WEST, a publication written specifically for Western herds. He is a graduate of Cal Poly-San Luis Obispo, majored in journalism and is known as a Western dairying specialist.