Probably.

But that often overused concept, which characterizes a fundamental change in approach or underlying assumptions within a science, an industry, or even individuals, may have at least some relevance to what appears to be happening as it pertains to milk production in recent months.

An about face

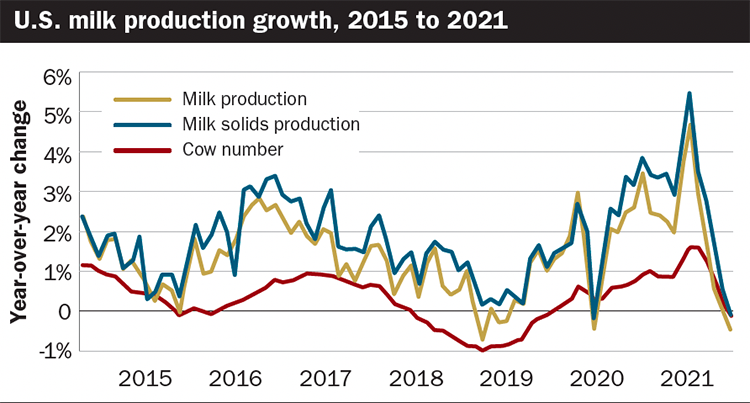

In recent months, USDA data shows an almost unprecedented unwinding of growth in cow numbers and production as shown in the figure. Based on preliminary data, from May to October, annual year-over-year growth in milk production dropped by 5.1 percentage points, and growth in milk solids was down by 5.6 percentage points. Both were the second largest downturns over a five-month period in more than a quarter-century. From June to October, growth in U.S. milking cow numbers declined by 1.73 percentage points, the largest such drop over the span of four months in at least 22-1/2 years.

This year’s lowest milk price-feed cost margins dating back to 2013 have no doubt played a role in this change. Even still, the numbers also give the impression that dairy farmers may have reached a collective tipping point after the past seven years in which there hasn’t been a really strong year for prices and margins. The well-publicized dispersals of dairy herds this year, including several large ones, may be further evidence of this unfolding situation.

What does this past history and current situation mean for the 2022 dairy outlook? A starting point is to examine what has happened to production and stocks of the major dairy products that are key determinants of milk prices. In short, reduced milk solids production in recent months has shown up almost entirely in lower butter and nonfat dry milk production and inventories, while those for cheese and whey continue to hold steady.

A deeper look

From the three months of March through May to the three months of August through October, total production and average stocks of butter were down by 21% and 16%, respectively. For nonfat dry milk, these same numbers were down 39% and 22%. But for cheese and dry whey, these numbers were between 0% and -3%.

As of November, butter prices were closing on $2 per pound, the highest since 2019. Nonfat dry milk prices were about to break above $1.50 per pound for the first time since 2014. Dry whey prices had also strengthened, but cheese prices had not yet caught a similar updraft.

As of mid-December, the dairy futures markets were clearly expecting the current tight production situation to persist well into 2022, with butter expected to average about $2.10 per pound, nonfat dry whey to average about $1.60 per pound, and dry whey about 63 cents per pound for the year. For nonfat dry milk and dry whey, these would be the highest annual averages since 2014. Prices of these two dry skim ingredient products have been buoyed in 2021 by tight world market prices, as import demand remains strong and milk production in Europe and New Zealand has been constrained.

The butter price outlook would represent partial recovery toward the sustained price levels of 2014 to 2019, which followed the major retreat from the decades-long nutrition advice against dietary consumption of animal fat. Cheese prices were expected to average $1.90 per pound next year, about where they were in 2020.

The mid-December futures price outlook indicates that Class IV prices would average about $1 per hundredweight (cwt.) above Class III prices. This would be a major change from recent years. Class III prices should finish out 2021 exceeding Class IV by about $1 per cwt., and these values were $4.68 per cwt. above Class IV in 2020. This class price outlook indicates that producer price differentials would be strongly positive in the component pricing orders, and there would be little Class III depooling in 2022.

A $22-plus price

This outlook would also imply the U.S. average All-Milk price would be about $22.50 per cwt. for 2022, almost $5 per cwt. above its average during the previous seven years. This optimism may be justified if the current constrained U.S. milk production situation proves to be durable in the face of higher prices. Lower milk production seems likely to continue in the other major dairy product exporting countries. But it’s also less clear how robust the current price outlook would remain in the face of a major surge in the Omicron variant of the coronavirus if it makes a significant impact on the U.S. food service sector, as previous variant surges have.

On balance, however, it looks pretty certain that dairy farmers can expect to find some relief in the new year from the prices and margins they’ve experienced in recent years and from the federal order disruptions of the pandemic years. But how much relief they will receive is not clear. Producers who are not already enrolled in the Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) program for the duration of the current farm bill should sign up for 2022 coverage before enrollment closes on February 18.