The author is a former extension veterinarian at Oregon State University, Corvallis.

On the farm, the best way to measure a calf's immune defenses is by testing for total protein (TP) in blood.

A good replacement program ensures that heifer calves make it to adulthood. Heifer raising starts from the moment she is born.

A clean calving environment means less exposure to pathogens and, therefore, less energy spent defending against the potential aggressors in the environment. The next step is to provide clean, good-quality colostrum, so she can gain passive immunity until she can produce her own defenses at about 2 weeks of age. It doesn't stop there; appropriate feeding every day is the only way she can naturally produce all the defenses she needs.

The term "failure of passive transfer" (FPT) is used to identify calves that do not achieve a specific concentration of Immunoglobulin G (IgG) in serum. The most common limit established in literature is 1,000mg/dL of IgG.

Because the tests available to measure IgG take time and require a lab, most farmers and vets use an approximation test by measuring the total protein (TP) in blood. You may have heard about different cutoff limits for TP anywhere between 5.0 and 5.5 g/dL. The reason for this variation is that TP includes not only IgG but other proteins as well, and can, therefore, be a bit "off" in different trials.

We know TP is the best available method in the field for now as it only requires a blood sample, a centrifuge or time to clot and a refractometer (manual or digital). The best time to test, however, is not as clear.

When and how to test

Thus, we conducted a set of studies at Oregon State University to take a closer look at FPT. In total, 673 calves were sampled over an 18-month period; 411 Jerseys and 262 Holsteins.

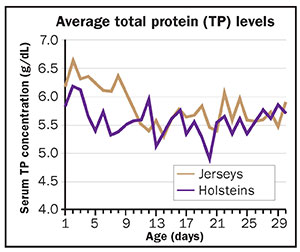

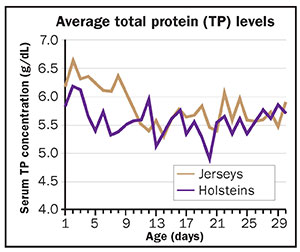

To identify the best time to test, calves from 1 to 30 days of age were sampled for TP (see graph). The results show that TP levels are highest at Days 2 and 3, and then they start dropping naturally. The importance of this is that, if we set the cutoff point for FPT at 5.5 mg/dL and test calves at 4 or 5 days of age, they may come in with levels of 5.2 mg/dL. We would classify them as having FPT when, in fact, they could have been okay on Day 2 and 3, but because we are on Day 4 or 5, the levels are already lower.

To identify the best time to test, calves from 1 to 30 days of age were sampled for TP (see graph). The results show that TP levels are highest at Days 2 and 3, and then they start dropping naturally. The importance of this is that, if we set the cutoff point for FPT at 5.5 mg/dL and test calves at 4 or 5 days of age, they may come in with levels of 5.2 mg/dL. We would classify them as having FPT when, in fact, they could have been okay on Day 2 and 3, but because we are on Day 4 or 5, the levels are already lower.

To avoid this misclassification, we can lower the limit for FTP, which is what some people do, or we can make sure every calf is sampled at 2 or 3 days of age to get the highest possible levels. Samples can be frozen and then tested once a month to detect the highest TP levels. According to results from our studies, dehydrated calves or those with fever did not show different TP or IgG concentrations compared to healthy calves, so all calves should be sampled.

Another question that we looked to answer was whether using serum or plasma was equivalent. A serum sample can be obtained by taking the blood sample in a red-top tube and either allowing it to clot or spinning it. A plasma sample is obtained by using a purple-top tube and spinning it.

According to our study, both samples yield equivalent results when tested fresh. However, if samples are frozen to be tested at a later time, serum samples can yield lower results, especially when frozen for more than three months. So, when planning to freeze samples and test them later, it would be better to take the blood in purple-top tubes and spin them before freezing.

Jerseys are different

Everyone who works with both breeds knows that Jerseys and Holsteins are very different. Jersey cows produce more protein and fat than Holstein cows, so, given that calf TP is dependent on colostrum intake, it makes sense that Jersey calves TP would be, in general, higher than that in Holstein calves, and our studies confirmed this.

This elevated TP concentration correlated inversely with IgG, so the resulting TP cutoff value corresponding to an IgG concentration of 1,000 mg/dL (FPT definition) was 5.1 g/dL in Holstein calves and 4.3 g/dL in Jersey calves. In other words, using a cutoff limit of 5.0 gm/dL for defining FPT in Jersey calves is too low, as they tend to have higher TP levels in general to those of Holstein calves, and at that level many Jerseys would be incorrectly labeled with FPT.

In fact, all Jersey calves had IgG concentration above the commonly accepted standard of 1,000 mg/dL (minimum was 1,150 mg/dL in a 10-day-old calf). Additionally, only 20 out of 411 (4.9 percent) of the Jersey calves had TP values less than 5.0 g/dL; all but one were over 10 days old.

Interpreting the results

TP values in newborn calves mainly indicate whether the calf had colostrum or not; the amount and quality of the colostrum cannot be tested by measuring TP. Yes, the more total IgG the calf gets through colostrum, the higher the TP will be. Still, the question remains: is it necessary to pump calves full of the best-quality colostrum available to keep them healthy, or are there other practices that help? Research has shown that allowing calves to suckle colostrum in small feedings (2 quarts, twice) is better than force feeding a full gallon all at once. We should think of what is best for that newborn baby calf, not only what is faster for us.

In our studies, there was no difference in serum TP (P=0.924) or IgG (P=0.348) between healthy calves and those that developed scours, pneumonia or both. Using the commonly accepted definition of FPT of 1,000 mg/dL of IgG and TP at 5.0 to 5.5 g/dL, there was no difference in the risk of scours, pneumonia or developing both diseases compared to healthy calves. This shows that clearly there are other factors besides how much colostrum and of what quality we give at birth that influences how well calves do until weaning.

We also compared growth rates (birth to 30 days) from several farms. It became obvious that calves fed more milk grew faster compared to those fed the standard 2 quarts twice a day. It is estimated that a calf needs at least 10 percent of its body weight in milk just for maintenance. That means that an average 90-pound calf would need just a little over 2 quarts twice a day for maintenance alone.

So, how do we expect the calves to grow feeding them at maintenance? For healthy development and growth, calves need at least 15 to 20 percent of their body weight in milk.

You can think about a calf as a checking account. You open the account when the calf is born with a large deposit, the colostrum. Then, every day you make small deposits with the milk being fed, and the body takes out small amounts of cash (energy) to use for daily exercise, maintaining body temperature and growth. When the calf gets sick, the body takes a large amount of cash to deal with the disease. If the bank account reaches zero, the calf will die. But, if the deposits we make every day (fed milk) are more than the amount of cash (energy) used every day, the calf should grow and thrive.

Click here to return to the Calf & Heifer E-Sources 150210_81

A good replacement program ensures that heifer calves make it to adulthood. Heifer raising starts from the moment she is born.

A clean calving environment means less exposure to pathogens and, therefore, less energy spent defending against the potential aggressors in the environment. The next step is to provide clean, good-quality colostrum, so she can gain passive immunity until she can produce her own defenses at about 2 weeks of age. It doesn't stop there; appropriate feeding every day is the only way she can naturally produce all the defenses she needs.

The term "failure of passive transfer" (FPT) is used to identify calves that do not achieve a specific concentration of Immunoglobulin G (IgG) in serum. The most common limit established in literature is 1,000mg/dL of IgG.

Because the tests available to measure IgG take time and require a lab, most farmers and vets use an approximation test by measuring the total protein (TP) in blood. You may have heard about different cutoff limits for TP anywhere between 5.0 and 5.5 g/dL. The reason for this variation is that TP includes not only IgG but other proteins as well, and can, therefore, be a bit "off" in different trials.

We know TP is the best available method in the field for now as it only requires a blood sample, a centrifuge or time to clot and a refractometer (manual or digital). The best time to test, however, is not as clear.

When and how to test

Thus, we conducted a set of studies at Oregon State University to take a closer look at FPT. In total, 673 calves were sampled over an 18-month period; 411 Jerseys and 262 Holsteins.

To identify the best time to test, calves from 1 to 30 days of age were sampled for TP (see graph). The results show that TP levels are highest at Days 2 and 3, and then they start dropping naturally. The importance of this is that, if we set the cutoff point for FPT at 5.5 mg/dL and test calves at 4 or 5 days of age, they may come in with levels of 5.2 mg/dL. We would classify them as having FPT when, in fact, they could have been okay on Day 2 and 3, but because we are on Day 4 or 5, the levels are already lower.

To identify the best time to test, calves from 1 to 30 days of age were sampled for TP (see graph). The results show that TP levels are highest at Days 2 and 3, and then they start dropping naturally. The importance of this is that, if we set the cutoff point for FPT at 5.5 mg/dL and test calves at 4 or 5 days of age, they may come in with levels of 5.2 mg/dL. We would classify them as having FPT when, in fact, they could have been okay on Day 2 and 3, but because we are on Day 4 or 5, the levels are already lower.To avoid this misclassification, we can lower the limit for FTP, which is what some people do, or we can make sure every calf is sampled at 2 or 3 days of age to get the highest possible levels. Samples can be frozen and then tested once a month to detect the highest TP levels. According to results from our studies, dehydrated calves or those with fever did not show different TP or IgG concentrations compared to healthy calves, so all calves should be sampled.

Another question that we looked to answer was whether using serum or plasma was equivalent. A serum sample can be obtained by taking the blood sample in a red-top tube and either allowing it to clot or spinning it. A plasma sample is obtained by using a purple-top tube and spinning it.

According to our study, both samples yield equivalent results when tested fresh. However, if samples are frozen to be tested at a later time, serum samples can yield lower results, especially when frozen for more than three months. So, when planning to freeze samples and test them later, it would be better to take the blood in purple-top tubes and spin them before freezing.

Jerseys are different

Everyone who works with both breeds knows that Jerseys and Holsteins are very different. Jersey cows produce more protein and fat than Holstein cows, so, given that calf TP is dependent on colostrum intake, it makes sense that Jersey calves TP would be, in general, higher than that in Holstein calves, and our studies confirmed this.

This elevated TP concentration correlated inversely with IgG, so the resulting TP cutoff value corresponding to an IgG concentration of 1,000 mg/dL (FPT definition) was 5.1 g/dL in Holstein calves and 4.3 g/dL in Jersey calves. In other words, using a cutoff limit of 5.0 gm/dL for defining FPT in Jersey calves is too low, as they tend to have higher TP levels in general to those of Holstein calves, and at that level many Jerseys would be incorrectly labeled with FPT.

In fact, all Jersey calves had IgG concentration above the commonly accepted standard of 1,000 mg/dL (minimum was 1,150 mg/dL in a 10-day-old calf). Additionally, only 20 out of 411 (4.9 percent) of the Jersey calves had TP values less than 5.0 g/dL; all but one were over 10 days old.

Interpreting the results

TP values in newborn calves mainly indicate whether the calf had colostrum or not; the amount and quality of the colostrum cannot be tested by measuring TP. Yes, the more total IgG the calf gets through colostrum, the higher the TP will be. Still, the question remains: is it necessary to pump calves full of the best-quality colostrum available to keep them healthy, or are there other practices that help? Research has shown that allowing calves to suckle colostrum in small feedings (2 quarts, twice) is better than force feeding a full gallon all at once. We should think of what is best for that newborn baby calf, not only what is faster for us.

In our studies, there was no difference in serum TP (P=0.924) or IgG (P=0.348) between healthy calves and those that developed scours, pneumonia or both. Using the commonly accepted definition of FPT of 1,000 mg/dL of IgG and TP at 5.0 to 5.5 g/dL, there was no difference in the risk of scours, pneumonia or developing both diseases compared to healthy calves. This shows that clearly there are other factors besides how much colostrum and of what quality we give at birth that influences how well calves do until weaning.

We also compared growth rates (birth to 30 days) from several farms. It became obvious that calves fed more milk grew faster compared to those fed the standard 2 quarts twice a day. It is estimated that a calf needs at least 10 percent of its body weight in milk just for maintenance. That means that an average 90-pound calf would need just a little over 2 quarts twice a day for maintenance alone.

So, how do we expect the calves to grow feeding them at maintenance? For healthy development and growth, calves need at least 15 to 20 percent of their body weight in milk.

You can think about a calf as a checking account. You open the account when the calf is born with a large deposit, the colostrum. Then, every day you make small deposits with the milk being fed, and the body takes out small amounts of cash (energy) to use for daily exercise, maintaining body temperature and growth. When the calf gets sick, the body takes a large amount of cash to deal with the disease. If the bank account reaches zero, the calf will die. But, if the deposits we make every day (fed milk) are more than the amount of cash (energy) used every day, the calf should grow and thrive.