The author is a recent graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison with degrees in dairy science and life science communications.

With a wealth of information about the care and treatment for calves on dairy farms available, it can be easy to forget some of the basics that have the biggest impact on calf health. I had a conversation with Sheila McGuirk, professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine, to go through the best practices to manage scours with your dairy calves.

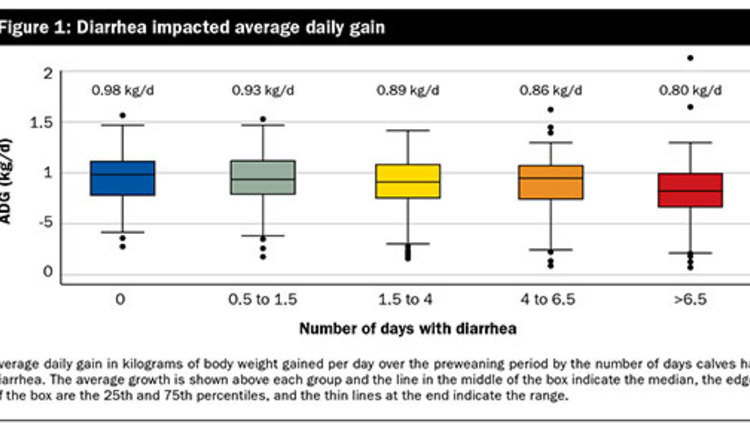

“Scours are a reality on dairies. Our goal is to keep it to the lowest number of cases possible,” said McGuirk. When looking for a benchmark, any time more than 20 percent of calves are sick with scours, it’s time to look back to the basics and see what we can do to prevent more cases.

Clean as can be

“The first step you can take on a farm to prevent scours is keep a clean calving environment,” stated McGuirk. While the best option for bedding is straw, that isn’t feasible on all farms. If the calving area is not perfectly clean, focus on getting the calf out of the calving area as soon as possible. When the calf starts trying to stand, it is likely to drag a wet umbilical cord through a dirty area or get a small amount of manure in its mouth. This exposes it to a scours organism right after birth before it gets any protection from colostrum.

“Given that the greatest risk period for getting scours is in the first 10 to 14 days of life, we need to minimize the chance of calves getting manure or manure-contaminated colostrum or feed into their mouth,” said McGuirk. Whether you are feeding two or three times a day, or with automatic feeders, the liquid or starter fed needs to be clean, of high quality, and precisely consistent.

Calves also need deep, dry, and clean bedding that keeps them deeply nested for warmth and distanced from manure and urine. The bottom line is the feeding equipment, water, bedding, and milk or milk replacer needs to be as clean as possible to minimize exposure to scours organisms.

For calves in group housing, be extra vigilant in keeping the calf environment clean. Scours organisms can build up in the environment, so providing adequate space per calf can minimize exposure. In group housing, there is calf-to-calf contact so “just like a kid at day care or kindergarten, once one gets sick, the chance that all will be exposed is much higher in group housing,” explained McGuirk.

The high level of nutrition from group feeding is a real advantage. It is essential, though, that the colostrum program be top notch and that nipple management minimizes the spread of scours organisms from one calf to another.

Prevent when you can

If scours are getting above 20 percent even with preventive measures in place, step back and take a look at colostrum management, nutrition, and the environment to find opportunities to do better. Good nutrition is a huge factor in the immunity of the calf and is especially critical in cold or damp weather. “Yes, the environment may present a risk for exposure to scours organisms, but good colostrum immunity and a high plane of nutrition make them less susceptible,” McGuirk said.

On breed differences, she shared, “It’s not necessarily a breed disposition to scours, but if we don’t watch Jersey calves and pay attention to their extra nutritional needs, they can be very susceptible to scours.”

A good vaccination program can be a very effective way to prevent scours. If vaccines to prevent scours are given to dry cows, make sure that the colostrum program is working to have success and justify the expense. “Vaccinating the calves at birth for scours or providing antibodies to scours organisms can also be an effective way to prevent scours cases, especially those due to viruses,” said McGuirk.

While the consistency of calf manure is a useful guide to scours management, not all calves with soft or slightly loose manure need treatment. Calves that are drinking 8 or 9 quarts of milk a day are going to have looser manure, and farms need to learn to be comfortable with that. If that calf is jumping around and eating everything in sight, they are fine.

However, calves with loose manure that are getting only 4 quarts of milk a day need to be treated right away. This is especially true when the manure reaches a point where it is as liquid as soup or watery and you can’t see it in the bedding.

If those calves have backed off feed or have a body temperature over 103°F or under 100°F, treatment is recommended. If a calf is standing with an arched back, has hair standing up, or is standing when the others are sleeping, it means that they don’t feel good enough to lie down and need attention.

“If it’s manageable, and especially on dairies with a history of a salmonella problem, being able to temp calves and catch early fevers is a benefit. However, it doesn’t need to be a routine practice, and you can find sick calves without temping them,” she noted.

Fluids are essential

“The treatment priority is keeping the calf hydrated,” said McGuirk. Dehydration can be pretty severe when a calf is scouring, and 10 percent dehydration (sunken eyes) is life threatening for a baby calf. The best tool we have to rehydrate calves is oral electrolyte solutions. They provide water, electrolytes, and energy, along with other factors that can promote absorption in the intestine. “When we find scouring calves early and they are willing to suckle, keep feeding them milk or milk replacer, but also give 2 to 4 quarts a day of the electrolyte solution,” McGuirk recommended.

“It’s essential that the calves on oral electrolytes have access to water,” she added. The electrolytes, sugar, and other ingredients will give them extra needs for water, and unless they have water available, they cannot drink.

“If a dehydrated calf won’t drink or it is too weak to stand, it is worth having employees trained by veterinarians to administer IV fluids,” said McGuirk. A relatively small volume of some hypertonic IV solutions can resuscitate some pretty sick calves and get them to drink water. That may be all that is needed to get some calves back to drinking milk and electrolytes.

“Not all calves with diarrhea need antibiotics,” McGuirk noted. She encouraged dairies to work with their veterinarians to establish criteria for when calves with scours need an antibiotic. Not many of the antibiotics approved for treating scours are effective, so it is important for you and your veterinarian to know the cause of scours when working out a treatment protocol.

Rehydration and meeting the calf’s need for glucose and potassium are primary treatment objectives. “If a dairy is wrestling with salmonella, antibiotics in the scours protocol may be very important,” she said.

Many times the simplest practices can have the biggest impacts on keeping calves healthy. Prevention is key for scours in dairy calves. A clean, dry environment for calves from birth through their first two weeks of life can go a long way in keeping those calves healthy. When you do need to treat scouring calves, work with your veterinarian to set up the best protocol for your farm so calves can grow into healthy, productive cows.